When imagining the ravages of World War I, it is easy to focus on the more than nine million soldiers who perished world wide. It is a horrific number to contemplate, and we rightly honor the fallen every year in veterans’ memorials around the world.

But there is another story of the Great War, a little-discussed one that deserves to be publicly lauded, about a group of Americans who banded together to save the Belgian people from starvation during the conflict.

When Germany invaded and occupied Belgium in 1914, it rapidly became evident that the Belgians would starve without outside help. America decided to spearhead an effort to get food to Belgium to ease the people’s impending starvation.

At the behest of Herbert Hoover, then a mining executive who would go on to become President of the United States, a group was formed: the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB). Once organized and operational, the CRB would become the largest relief effort the world had seen up to that date.

Most of its members were students, on a break from their academic endeavors. Ships would arrive in Belgium bearing the CRB banners, and then CRB members drove food and supplies across the country. It was no easy task: there were German soldiers everywhere, and the Belgians were not accustomed to taking what they felt, at first, were handouts.

A new book about this one bright spot in the war’s history has been written by Jeffrey Miller, entitled WWI Crusaders: A Band of Yanks in German-Occupied Belgium Help Save Millions from Starvation as Civilians Resist the Harsh German Rule. August 1914 to May 1917. Miller’s own grandfather was one of the Americans involved in the effort.

Although there were fewer than 200 volunteers on this mission, what they accomplished was enormous, and their efforts forever altered the way relief efforts are handled globally. Miller is passionate about reminding the world of what America did during those dark days.

“This is my whole life’s work,” he enthused in an interview, “to tell Americans, this is a story we should learn about…it’s always good to look at the past as a chart towards where we should go in the future. We did this totally without any self interest; we went in there without any transactional thought in mind.

“There was nothing expected in return; we did it because it was morally and ethically right to do.”

The Belgians had been stockpiling food, but in a country that depended on outside sources for 75% of its products, that was not enough. What little they managed to store ran out quickly.

Perhaps surprisingly, the German occupiers did not undermine the aid, Miller explains. They needed their soldiers at the front, not in cities controlling civilians. Hence, their rationale was that if the Belgians were fed, they would be easier to control.

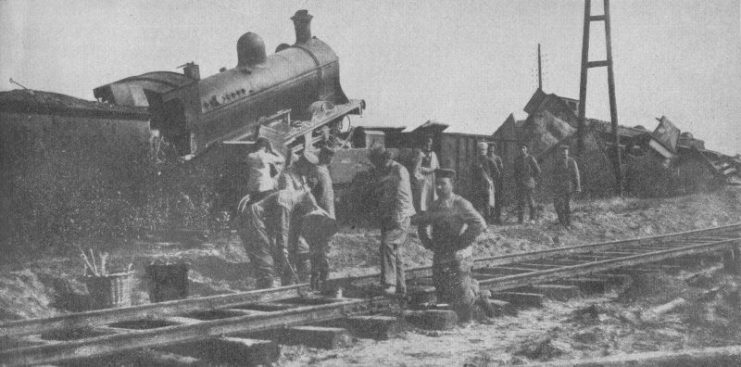

The relief effort was a massive undertaking that took significant coordination of ships, canal barges, and vehicles. Once arrived in Belgium, the food was transferred, Miller explained, “by 40,000 Belgian volunteers, who prepared the food and distributed the food to nearly 10 million civilians.” The American men drove around to bakeries and warehouses, in part to ensure that no Germans “were stealing the food,” Miller added.

Read another story from us: Two Invasions of Belgium By Germany in Two World Wars: 1914 and 1940

“No one ever thought it could be done,” Miller said. “So it was an incredible operation…everyone only talks about the trenches; they talk about the killing. Just over nine million soldiers died in the First World War; well, Herbert Hoover saved just over nine million people from starving during the First World War. So there’s some great symmetry there, I think.”