He was transferred to a POW work camp that had been erected in a baseball stadium. The conditions in the camp were harsh and the rations were scarce.

One of the things Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Air Commodore Leonard Birchall is most remembered for is being the “Savior of Ceylon.” He was the pilot who warned the Allied forces in Colombo of the Japanese surprise attack that was on its way, thus allowing them to prepare and preventing a repeat of Pearl Harbor.

However, he showed the true breadth of nobility and valor of his character in Japanese prisoner of war camps over a period of three years, in which he saved many men’s lives and took many prisoners’ beatings for them.

Leonard Birchall was born in July 1915 in St Catharines, Ontario, in Canada. From an early age he had been fascinated with airplanes and flying, and after graduating from school he worked a number of jobs in order to pay for flying lessons.

He eventually decided to embark on a military career, and enrolled in the Royal Military College of Canada in 1933, after which he was commissioned as a RCAF pilot in 1937.

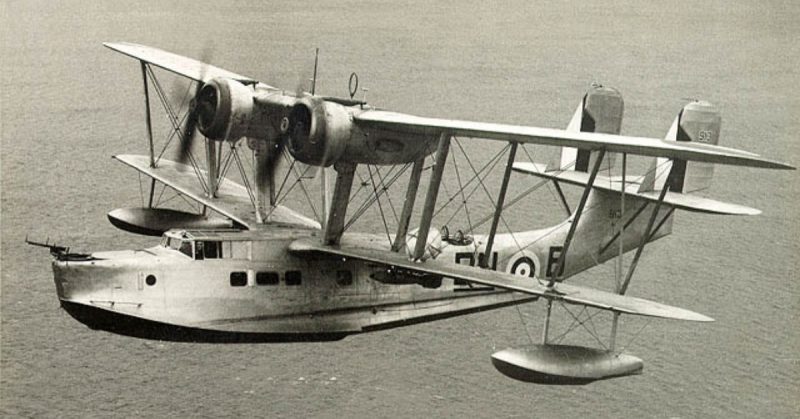

It wouldn’t be too long before he saw action: the Second World War broke out in 1939, and Birchall got involved from the very outset. His first duties involved flying a Supermarine Stanraer with RCAF No. 5 Squadron over Nova Scotia on anti-submarine patrols.

In 1940, he managed to virtually single-handedly capture an Italian merchant ship in the Gulf of St Lawrence by making a low pass over it, feigning an attack, which caused the captain to panic and run his ship into a sandbank. Birchall landed nearby and waited patiently for the Royal Canadian Navy to get there, whereupon they arrested the Italian seamen.

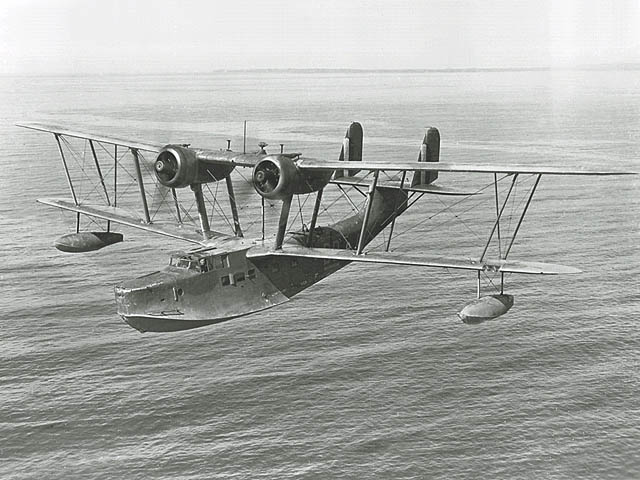

In 1942 he joined No. 413 Squadron, and shortly thereafter was transferred to Ceylon (now called Sri Lanka). Upon arriving in Ceylon, Birchall saw action almost immediately. Less than 48 hours after touching down, he was flying his Catalina on a patrol mission when he caught sight of an Imperial Japanese Naval fleet which was clearly on its way to attack Ceylon.

Birchall didn’t have much time to act, for not only had he spotted the Japanese, but they had also spotted him. Despite the imminent danger, Birchall flew closer in order to gather details about how many ships and aircraft he could see.

He desperately relayed details to the Allied base even as anti-aircraft fire starting ripping past him, while Japanese fighters took off from the aircraft carriers to shoot him down.

He managed to get a few messages through to the base before anti-aircraft fire tore through his Catalina and disabled the radio. Further fire crippled the plane, and he went down, crash-landing into the ocean. He and the other surviving members of his crew were picked up by the Japanese and taken onto one of the ships. Thus began three years of imprisonment.

As soon as Birchall was brought on board the Japanese destroyer Isokaza, he was singled out as the senior officer and brutally interrogated. Despite being beaten and tortured, Birchall repeatedly denied that he had sent out any messages before his plane was destroyed.

The Japanese eventually believed him, and went ahead with their attack – but they found the Allied defenders prepared for them, and their raid was a failure.

Birchall was then transferred to mainland Japan, where he was incarcerated at Yokohama. He was placed in an interrogation camp, in which he was subject to solitary confinement and daily beatings. In this camp – in which no speaking (except when answering questions) was allowed – Birchall spent 6 grueling months.

After this, he was transferred to a POW work camp that had been erected in a baseball stadium. The conditions in the camp were harsh; rations were scarce, and the prisoners were basically on a starvation diet. Beatings were commonplace, and everyone, regardless of their physical condition, was forced to work.

Birchall immediately began to earn the respect of the other prisoners by arranging a system in the camp whereby he and the officers displayed the food that had been dished out to them, and if any enlisted man thought that the officers had been given better food, or more food, he was free to exchange his rations with the officer’s.

He also gave up smoking and convinced the other officers to do the same, as cigarettes were the only items that gave the men in the camps any kind of relief. He and the officers thus donated their cigarette rations to the enlisted men. He also made sure that no heavily addicted smoker would trade their food rations for cigarettes.

Despite the risk of severe punishment, he also argued with the guards and demanded better treatment and rations for his men. If a guard was beating a particularly weak prisoner, Birchall and the other officers would step in and take a beating from the guards on that prisoner’s behalf.

On one occasion, a guard refused to stop beating a particularly sick prisoner, so Birchall intervened, as he always did – but this time he used his fists. For attacking a guard, he was tortured to within an inch of his life, but even after this, he again led his fellow prisoners in a strike, refusing to work until the guards agreed not to beat and mistreat very ill men.

For this, though, Birchall was sent to a severe discipline camp in Tokyo, where he was subjected to more brutality. Even then the Japanese couldn’t break his spirit, and he continued to inspire his fellow POWs. After this he was sent to a camp in the mountains outside Tokyo.

After three and a half years of imprisonment, Birchall was finally freed by Allied troops after the Japanese surrender. In the POW camps at which he had been imprisoned, he had succeeded in boosting morale, improving treatment of the prisoners, and making things more efficient to the point that the death rate of some camps dropped from over 30% to around 2%.

Read another story from us: Little-Known Photos of Canadians During D-Day

Birchall kept detailed diaries of his time in the Japanese POW camps, and these were used as evidence in post-war trials. He was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions in Ceylon, and made an officer of the Order of the British Empire for his actions in the POW camps.

Leonard Birchall retired from the RCAF in 1967, and then worked at York University, Ontario, until 1982. He passed away at the age of 89 in 2004.