On February 27, 1916, the Norwegian cargo ship Rena steamed out of Cuxhaven on Germany’s North Sea coast. In peacetime, this would not have been anything out of the ordinary. However, it was the height of WWI, and not everything was as it seemed.

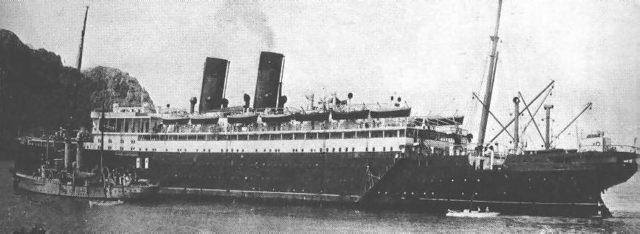

In fact, Rena was the third name the ship had held is as many months. Originally built as the Guben, she was launched in 1914 for the German-Australian Line, but her career was short lived. Launched again on July 29, her home port was blockaded by the Royal Navy once war broke out, in August. She was now forced to sit in port, waiting for her chance to escape, and plow the seas as she was meant to.

That opportunity had come when she was commissioned into the Imperial German Navy as SMS Greif. Now a merchant raider, she was designed to sneak past blockades, and attack shipping lanes on the high seas.

The Germans intended to prevent supplies reaching the British people, by restricting their ability to trade with foreign nations. She was armed with four 15cm SK L/40 cannons, one 10.5cm SK/L 40 rapid fire cannon and two 50cm torpedo tubes. These weapons were all hidden behind steel covers, and the aft gun was camouflaged in a false steering house, masking the ship as an unassuming cargo steamer. By February, her transition to a merchant raider was complete.

She pulled out of Cuxhaven, heading northwest into the North Sea, hoping to skirt around England safely. She was planning to attack the valuable wheat shipments coming from Rio De La Plata, which always left in late February, and would be easy targets in the middle of the Atlantic.

She was escorted by U-70, who proceeded 40 nautical miles ahead. However, the Royal Navy had caught wind of her movements.

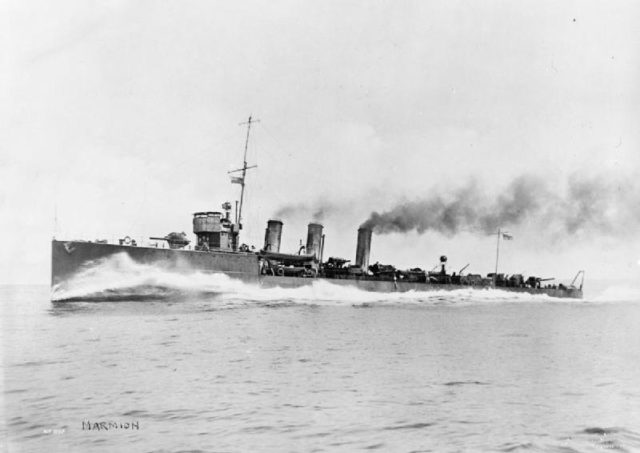

Royal Navy Admiral Sir John Jellicoe dispatched two cruisers and a destroyer from Rosyth Naval Base together with a trio of light cruisers and a destroyer from Scapa Flow. These ships patrolled up and down the Norwegian coast, creating a broad net. They were not sure if the reports of a lone steamer were accurate, but they could not risk a commerce raider getting out into the open ocean.

Other raiders, such as the Prinz Eitel Freidrich and Cap Trafalgar, had already wrought havoc patrolling the seas unrestricted. These former commerce raiders had been dealt with. Prinz Eitel Freidrich was starved of coal, and Cap Trafalgar was sunk, but it was feared that any new threat to English shipping could potentially tip the war into Germany’s hands. Admiral Jellicoe knew, as did the crews of his ships, that these new raiders had to be stopped.

Midnight on the 27th, British radio detection equipment located a German signal coming from around the Egersund area, off the southwestern coast of Norway. Their fears were confirmed, and now their net tightened. However, for two days nothing showed itself.

Onboard the Greif, the atmosphere must have been full of both fear and excitement. The crew was finally breaking free of the British blockade, and able to take revenge for what the Royal Navy had done to Germany’s economy and food supply, depleting both amidst an ever more pressing war.

They were not out of the forest yet as they continued to evade British ships. They knew that until they got past the Shetlands, and into the open ocean, they could not be free to roam.

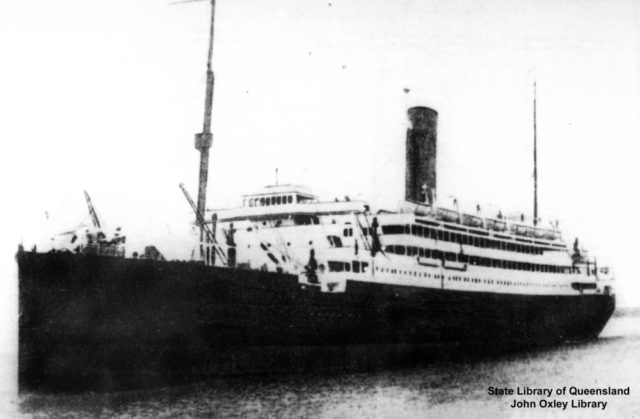

At 0800 on February 29, HMS Andes, an auxiliary cruiser in the Royal Navy was set to relieve HMS Alcantara, another auxiliary cruiser. Alcantara had been patrolling around the Shetland Islands for the past two days, the last line of defense in the British blockade, never expecting to be the front lines. Her patrolling almost over she was dangerously low on coal and needed to refit in Liverpool. The two ships were told to meet and exchange east of the Shetland Islands, but then Alcantara received an order to stay put; the German raider was expected to be in that area soon.

By 0845 Alcantara, under the command of Thomas Wardle, spotted smoke on the horizon. She moved to investigate, knowing that this lone steamer could very well be the commerce raider. As she approached, her officers saw the Norwegian flag, and RENA painted in large letters on her stern. There was a record of such a ship existing, but to be safe, Wardle ordered her to heave to and prepare for an inspection. Even if it was not the enemy ship, they should still inspect the cargo to see if it contained contraband from Germany.

On board the Greif, the crew rushed about, just out of sight of the enemy. Guns were prepared, ammunition laid out, and every man armed to the teeth. They knew these fights could easily come down to rifle fire, especially at such a close range. Alcantara pulled towards them.

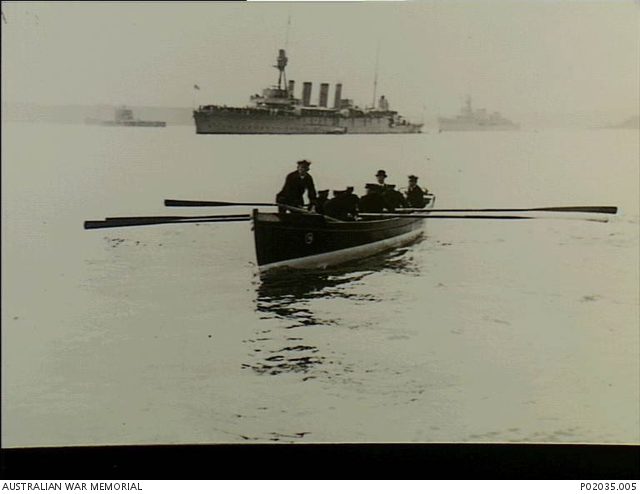

At about 1000 yards astern of the Greif, the Alcantara dropped a boat and sent a boarding party towards the Norwegian steamer. Wardle then received a message from the Andes, who had been pursuing another vessel, that this ship was suspicious. He agreed, but it was too late to recall his boat.

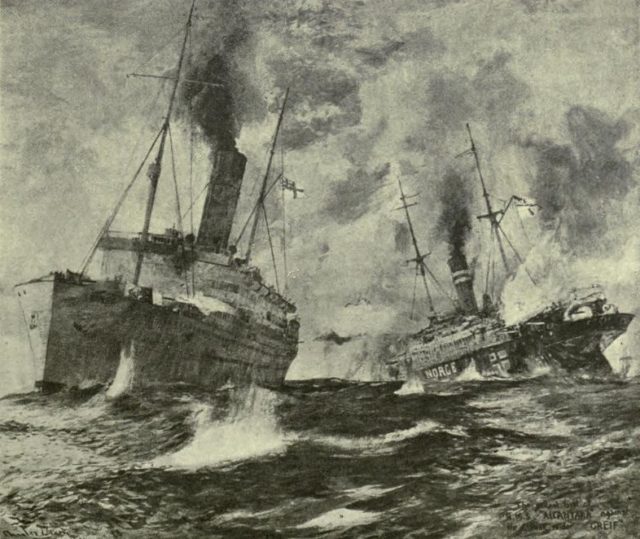

Suddenly, all hell broke loose. What appeared to have been the steering house at the stern of the Greif disappeared, and in its place stood 10.5cm cannon. Along the sides, covers fell open, revealing more deck guns. All opened fired on the Alcantara and her boarding party, sending spouts of water shooting towards the sky.

Greif’s shells struck home, and destroyed Alcantara’s steering gear, leaving her unable to maneuver. Her gunners returned fire, and for 15 minutes the two auxiliary cruisers exchanged blows. Shortly after fighting began the Andes arrived and joined the fight against the Greif.

By 1100, the German ship was cloaked in smoke from fires onboard. The Alcantara was listing heavily, and a large hole below her waterline gushed with water where she had been torpedoed. The Andes had signaled for help and was watching cautiously as the German ship ceased firing, and lifeboats began to pull away from her. The cruiser HMS Comus and destroyer HMS Munster arrived on the scene, dealing the final death blows to the lone German ship. Greif and the Alcantara sank soon after.

SMS Greif went down with around 130 of her 360 man crew and Alcantara with 68 men. While small actions like this rarely get a mention in history books, they are necessary for understanding the desperation of both Navies.

The Germans knew their only hope of survival was to break through the British blockade, either with merchant raiders or submarines and attack the British shipping lanes.

The Royal Navy knew their nation depended on them to keep Germany blockaded, to starve the country into submission, and prevent any German vessel from threatening British trade. The men who died that day, German or British, died knowing they were doing all they could to protect their nations.

The Royal Navy knew their nation depended on them to keep Germany blockaded, to starve the country into submission, and prevent any German vessel from threatening British trade. The men who died that day, German or British, died knowing they were doing all they could to protect their nations.