War History Online presents this article from Jack Snowden

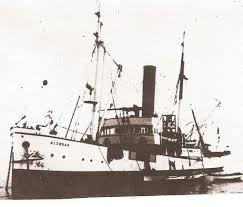

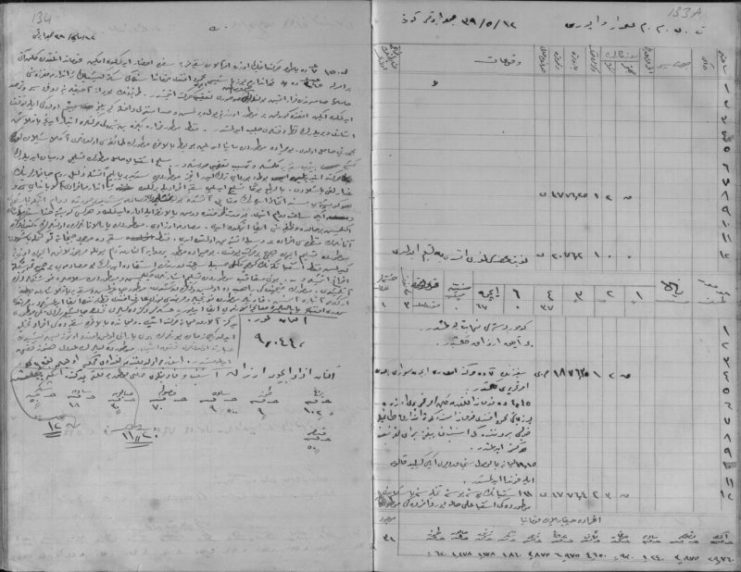

The source for the adventurous tales of the Alemdar are two ship’s logs, the first of which reflects the daily activities of the Alemdar between June 1921 and May 1922. After having been spirited away from British-occupied Istanbul in January 1921 by a crew loyal to the leader of the Turkish independence movement, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the Alemdar remained in Ereğli on the western Black Sea coast for many months, effectively under the watch of the French navy, then in control of the area.

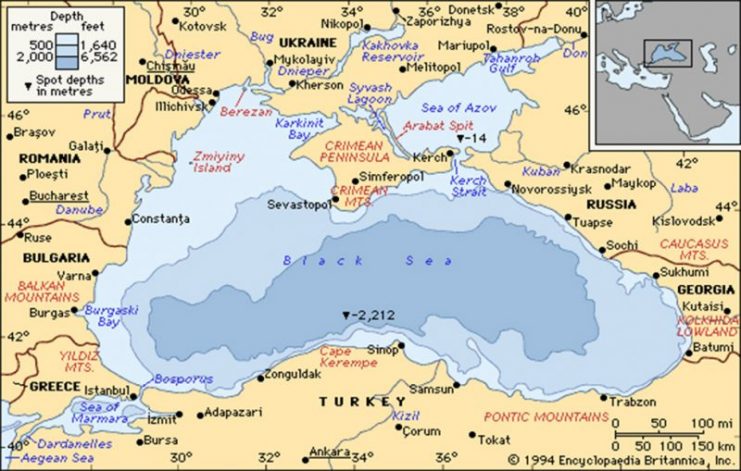

When the first ship’s log begins in late June 1921, the Alemdar is being readied for a daring escape from Ereğli to take up duties for the independence movement in Trabzon, in the eastern Black Sea region. However, French and Greek naval pressure kept the Alemdar stuck in Ereğli harbor until 24 October, at which time the crew used the cover of a fierce storm to escape to Trabzon.

The ‘Alemdar’ was hijacked by Kemalists from Istanbul to Ereğli, near Zonguldak, in January 1921.

Once at Trabzon, the Alemdar began ferrying arms and ammunition that had come from Bolshevik Russia to central Black Sea ports like Samsun and Inebolu, from where the material was transported overland to Ankara and onward to the front lines of the ongoing Turkish War of Independence, being fought against the Greeks, further to the west in Anatolia.

Besides this essential duty, though, unexpected missions for the Alemdar were reflected in the ship’s log. For example, after delivering weapons and goods at Samsun, on 14 November the Alemdar took on ’62 German and Bulgarian prisoners’ who were transported to Trabzon and given over to the custody of military officers from the independence movement there.

Subsequent research has revealed that the Samsun office of the Turkish Red Crescent was involved in the repatriation of these World War I POW’s, who had been held in French prison camps in north Africa during the war.

Given that the war ended in November 1918, it is surprising that these German and Bulgarian prisoners would be still languishing on the north coast of Turkey three years later. Perhaps even more surprising was their transport to Trabzon aboard the Alemdar.

By the end of November 1921, the Alemdar was on its way to Russia for the first time. The destination was Novorossisk on the northeastern coast of the Black Sea and the Alemdar towed two motor gunboats behind it all the way there. The gunboats had been given to the Turkish independence movement by the Russian Bolsheviks but, in need of repair, they had to be returned to Novorossisk.

Months later, these same two gunboats would capture a Greek vessel near Novorossisk and bring it back to Trabzon, where it was converted for use by the independence movement. The Alemdar remained in Novorossisk for four months, waiting to take on guns and ammunition from the Bolsheviks.

Finally, in mid February 1922, the Alemdar returned to Trabzon with its precious cargo. Routine duty resumed along the Black Sea coast between Trabzon and Samsun but in April 1922 a new captain took charge of the ship, Mustafa Ercivelek. It was Captain Ercivelek who kept the two ship’s logs safe and secure within his family for years. The logs were finally transcribed to modern Turkish from Ottoman in 2013-2014.

The Alemdar, up to this point a salvage and transport ship, was outfitted with cannons in May 1922 and essentially assumed the additional duties of a warship. Subsequent sea battles in the Black Sea with Greek rebels – in November 1922 with the Pontus Abacı Yanko gang near Samsun and again in May 1923 with the Sarı Yanni gang near Trabzon – ended successfully for the Alemdar both times.

In the first case, the event occurred during a period not covered by the source ship’s logs. The second encounter, however, was well-documented in the ship’s log, whose entries from the day in question – 12 May 1923 – reflect the high drama of the confrontation.

Nevertheless, the next day, 13 May, the Alemdar was off on a new mission, this time sailing to Batumi to pick up Caucasus refugees for transport to Trabzon and points elsewhere in Turkey. At times, 300 to 400 refugees, their goods and even their animals, were loaded onto the Alemdar for the trip to Trabzon.

The remaining months of the ship’s log record reflect more trips to Russia to pick up arms and ammunition, continued arms-ferrying duty along the Turkish Black Sea coast, refugee transport missions and salvage operations. In October 1923, the crew of the Alemdar spent an enormous amount of effort to free the Şahin, a large transport ship that had run aground at Amasra.

The mission ended unsuccessfully and the Alemdar then headed for Istanbul, by this time under the control of the new Turkish government of Mustafa Kemal. Fittingly, the Alemdar had returned to Istanbul, from where it had escaped nearly three years earlier.

Thanks to the Alemdar’s ship’s logs, the dramatic events that consumed the ship during the period covered can now be assessed more fully. In addition, the logs provide a rare glimpse into the fine points of Black Sea maritime activity at the time, reflecting day-to-day operations of the ship and the crew.

The entries in the Alemdar logs are generally brief and do not provide many details of related activities going on around the ship. Fortunately, in some cases alternative sources have helped to flesh out events involving Alemdar. One such incident occurred during Alemdar’s voyage from Trabzon to Giresun in April 1923, registered blandly in the log without amplification.

In fact, based on a book subsequently written by Alemdar crewmember M. Celaleddin Orhan, we learn that the Alemdar had received an order from Ankara to sieze the Fulya motorboat, which had been stolen from the Greeks and was in the possession of Topal Osman, the assassin of Trabzon Parliamentarian Ali Şükrü Bey, now in Giresun with his men. Alemdar’s captain, Mustafa Nail Ercivelek, ordered Orhan to go to shore with a few soldiers and seize the Fulya in the dark of night.

Orhan and his men went to the local village and had the locals take them up to a ridge from where they could survey the location of the Fulya. Later that night, Orhan and his crew secretly and silently boarded the Fulya, all the time expecting shots to be fired from Topal Osman’s men high on the ridge above.

Within two hours Orhan and his men had freed the Fulya from its chains and the motorboat was tied to Alemdar for towing to Trabzon. But not a word about this derring-do is reflected in the ship’s log.

No doubt there are many other fascinating stories that may yet emerge from the Alemdar ship logs. For example, the full stories behind the “62 German and Bulgarian prisoners” boarded on the Alemdar and handed over to Turkish authorities in Trabzon on 16 November 1921, along with the transfer of “3 German prisoners” from Trabzon to Batumi aboard the Alemdar in June of 1923, would certainly provide fascinating angles. Similarly, the background and subsequent events related to the transport of hundreds of refugees from Batumi to Trabzon in 1923 bear closer examination.

In any event, the unique information included in the logs provides a rare glimpse into the Black Sea environment during the Turkish War of Independence and the mechanics of the transfer of vital arms and ammunition from Bolshevik Russia to the Turkish nationalist forces.

All photos provided by the author Jack Snowden or Public Domain