War History Online presents this Guest Article from Szymon Serwatka

Mission completion in sight

They took off early on the morning of June 21, 1944, from the English base of the 452nd Bomb Group (8th Air Force) at Deopham Green. Their target was the synthetic fuel plant at Ruhland (between Dresden and Berlin, Germany). But this was not a routine mission because after hitting their target, they continued flying east, over German-occupied Poland and across the Soviet frontlines. Their final destination was the airfield leased by the US government from the Soviets near Poltava, Ukraine. The mission was going smoothly and almost uneventfully …

“…The view from my position in the B-17 glass nose was wonderful. It was a sunny day with rare small clouds below us, and I could see the shadows of our planes skimming the fields and forests of Poland. I was wondering what people down there were thinking when they saw us. There was only one last checkpoint on my list as the navigator – the airfield in Poltava…”

The next thing Alfred Lea remembers is the B-17 shaking from a hit by an invisible enemy. Bill Cabaniss, the ball turret gunner, yelled into the intercom: “Eleven o’clock!!! Below us!!!” Alfred looked down and saw the blazing guns of a Bf-109 which was climbing almost vertically above the clouds. It was perfectly visible – black with an orange tail.

It then dove down under their left wing, and it was so close that Alfred saw the pilot’s white scarf. The German pilot was a professional and made an expert quick pass. Both the bomber’s internal engines had been hit and stopped working; there was a gaping hole in the wing, and the shattered remains of the fuel tank were burning. The intercom was full of the nervous voices of the crew, and all were dominated by the pilot who yelled: “Jump! Jump!” Then the alarm bell rang. Within those few seconds, they had been shot down.

Bailing out

Alfred Lea rushed to the escape hatch but could not open it. It was obstructed by twisted metal from the plane’s skin. Alfred used his full strength to kick the hatch with both feet and it flew off. He found himself hanging under the bomber, because his chest parachute had become stuck in the opening. The B-17 started spinning, and he was afraid he would hit the ball turret if he immediately freed himself. With difficulty, Alfred pulled himself back inside. The aircraft was already low and falling at speed. It could fall apart at any moment. The bombardier was still there and Alfred told him: “Come on, Baker, you go!” but he replied: “No, Al, I will go after you”. Alfred summoned all his remaining strength and jumped out head first.

In the cockpit, Louis Hernandez and Thomas Madden were struggling to maintain control of the plane long enough for the crew to jump. Hernandez braced his feet against the instrument panel to exert his full strength. Madden helped until he too bailed out. When he let go of the controls, the B-17 lurched violently. The control wheel snapped forward and pulled Hernandez’s right arm out of its shoulder socket. His next recollection was being on the ground.

Bill Cabaniss had been wounded, and one of the crew pulled him from the ball turret. Bill was unconscious so another airman grabbed him and dragged him out of the open rear door. They fell together, and then the crewman opened Bill’s chute and continued to freefall for another few seconds before opening his own parachute.

For Alfred Lea, when he jumped it had suddenly become quiet. He remembered being told German pilots shot at airmen hanging under their parachutes, so he waited before pulling his ripcord. When he could make people out on the ground he pulled but nothing happened! The ripcord was severed, so Alfred had to quickly open the chute by hand. The shock tore his boots off and he went barefoot for 30 days. Years later, looking back, he said it had helped him treat his athlete’s foot.

Landing in the Polish countryside

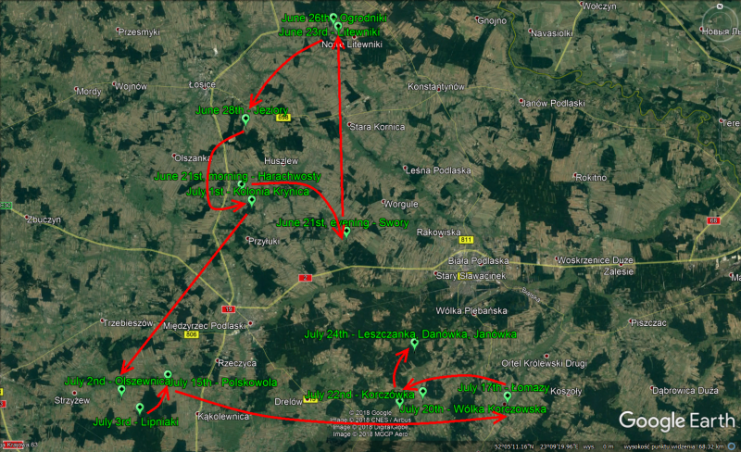

Meanwhile, the Partisan Unit of the 34th Home Army Infantry Regiment was enjoying a warm summer day. They stayed in the village of Harachwosty. Officers, including Commander Lt. Stefan Wyrzykowski (Zenon)), played bridge. Stanisław Lewicki (Rogala) remembered:

“We heard the noise of the aircraft, but the activity in the air was common those days, so we did not pay attention. Suddenly a soldier rushed into the house urging us to go outside and look. This time, there were very many aircraft and they were different from those we used to know. Zenon became angry because he had very good cards and he sent the soldier away. The game was interrupted again by the sound of cannon and gunfire coming from the sky. The same soldier rushed into the house again reporting a shot down aircraft and people jumping with parachutes.”

The officers dropped their cards and ran outside. They had never seen B-17s before. They could see many planes, going in a large formation from west to east. Someone counted small figures floating in parachutes. There were 10 of them. Zenon took the cavalry and horse-drawn machine guns and rushed towards the area where the airmen would soon land.

When Alfred Lea landed a Bf-109 strafed the field so he hid his parachute under some trees and ran in the direction of another flyer who landed close to him. It was the bombardier, Joe Baker, and they decided to seek shelter in the nearby village. They saw a group of peasants harvesting a field and crawled closer to them to check if they were friendly or hostile. The Americans were spotted by a limping elderly man with a scythe. His limping was faked, as he was hiding a bottle of water – he did not want to draw attention from a German patrol nearby.

Lea and Baker changed their minds, deciding reaching the village would be too risky. They saw a single house on the other side of the road and wanted to try their luck there. Suddenly, the airmen heard lorries approaching, and hid in a culvert under the road. Several trucks full of German soldiers stopped right over them. The Americans considered surrendering but were afraid they would be executed, so they stayed in the culvert. The Germans did not look there and finally drove away after some time.

The Americans cautiously approached the farmhouse. They checked the surroundings, and then knocked at the door. The farmers turned out to be friendly and served a meal of bread, eggs, and sour milk to their unexpected guests. Baker was not particularly fond of the milk, but Lea was not complaining. They were halfway through the meal when 5 armed men entered the house. Their uniforms were different and the Americans understood they were resistance fighters. Communication was difficult because of the language barrier, and everybody was in a hurry. The partisan leader showed with signs the airmen should go with them. They ran to a nearby forest where they saw the horse-drawn cart with a machine-gun on a tripod. Lea and Baker were safe.

The next thing Hernandez remembered after fighting the controls of the doomed plane were 3 Polish girls trying to help him. They took him to a nearby house, where another airman, Hutchinson already was. The B-17 had crashed about 100 yards from the house, so it was important to get them away as fast as possible. The Polish men bundled the airmen in blankets and left them in a field of tall grain. Partisans came later and took them to join the other Americans. Hernandez and Hutchinson rode on a horse-drawn wagon escorted by partisans on bicycles, who kept a sharp lookout for Germans.

Lea and Baker arrived at the village of Swory, which appeared to be the partisans‘ headquarters. They met 5 more crew members there. The partisans radioed a report to London to inform them that seven Americans were safe:

Pilot Louis Hernandez,

Co-pilot Thomas Madden,

Bombardier Joseph C. Baker,

Navigator Alfred R. Lea,

Flight engineer Anthony Hutchinson,

Waist gunner Herschell L. Wise,

P-51 mechanic Robert L. Gilbert

The remaining three men were captured by the Germans and returned to the US after the war:

Radio-operator Jack P. White,

Tail gunner Arnold Shumate,

Ball turret gunner William Cabaniss.

The Partisan’s wireless operator had trained in England and was then dropped in Poland by parachute. The radio was powered by electricity produced by a generator mounted on a bicycle. The sprocket could be shifted to enable the rider to power the generator.

The Partisans also sent for a doctor for Hernandez, and the elderly man had to walk 5 miles in darkness to help the American. Hernandez was given a few shots of vodka, and then the joint was put back in position while the pilot was pinned to the ground by the doctor’s body.

The Americans had noticed upon landing in the Polish countryside, how their parachutes and Mae Wests were taken by Polish girls. Only later they found out many clothes and other necessities were made from them. Some of the fabric was unraveled to make thread for surgical sutures. Parachute harnesses were used to repair horse harnesses.

The airmen were extremely happy because they had not had any prior information of what to expect if shot down over Poland. They knew they could get help in France, Belgium, or the Netherlands, but nothing had been said about Poland. Alfred Lea and his friends were stunned to see in the following few weeks how well organized and trained the Polish Home Army was.

Living a Partisan’s life

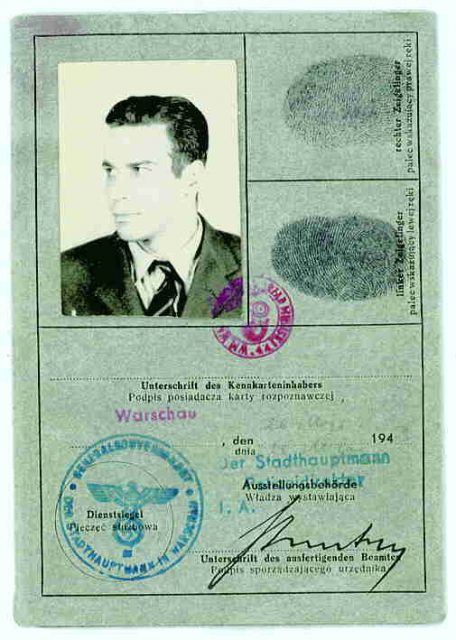

The Americans shared the Partisans way of life with their new Polish friends. The interpreter was a soldier known as Dreadnought (Zygmunt or Tadeusz Szarfa Liniowiec). All partisans used such names, to hide their real identities from the Germans and to protect their families. Alfred Lea was Mueller, because – according to the Poles – he had a very German look. It is not known if the Americans knew that the Partisans gave them a collective nickname Afrykańcy (Africans). The language barrier was still difficult, because Dreadnought knew British English, and the airmen spoke American English. The flight engineer, Anthony Hutchinson, was from Georgia and had a heavy southern accent. Other Americans frequently had to translate what he said to something „Dreadnought“ could understand. They taught „Dreadnought“ some of the American slang, and he had fun with it.

In the next days, Americans helped Polish partisans, who became very busy disturbing German supply lines, as the frontlines were coming closer and closer. According to Lea, when the unit had a military action, they were not frightened of the Germans, and were very well organized and systematic. Poles had a sophisticated system of sentries and signals ahead and behind the moving unit. Lea commented on one occasion: „they impressed us as a genuine military organization and were as well disciplined as any unit in the field“. The Polish partisans carried heavy water-cooled machine guns, German-made rifles, pistol, and automatic weapons. Some wore Polish pre-war military uniforms, some had battle-dresses, some used captured German uniforms, but all proudly wore the Polish national insignia – the eagle – on their hats and caps. All were clean and tidy.

One day, Americans witnessed a major battle with the German forces, composed of Russians who were recruited from Soviet POWs. The enemy approached the village where Polish partisans made a stop. Poles retreated to a nearby forest, which gave them better protection. Germans retreated, but ‚Zenon“ knew they would come back in greater numbers. He collected all his men, totalling around 200. As expected, Germans returned in the force of 500 men. Enemies had light artillery and a tank, and tried to encircle the partisans. The battle lasted 5 hours, and Germans had to retreat, leaving 50 dead and many more wounded. This battle provided more adventure to Louis Hernandez and Herschell Wise.

When the partisans had to retreat to the forest, Hernandez and Wise could not run as fast, and when the saw the German tank coming, they fell to the ground, and stayed there for a couple of hours until the battle was over. Then, they waited until dark, and ran away as far as they could. They ran for the most of the night. In the morning, they met an old Polish farmer, made him understand they were Americans, and he hid them in his barn, in the hay. A few hours later, Germans came to the barn, and started to search the hay. But when they saw chicken on top of the hay, they figured out there would be noone hiding there, and left. Both Americans would be reunited with the „Zenon“ unit and the remaining Americans a few days later.

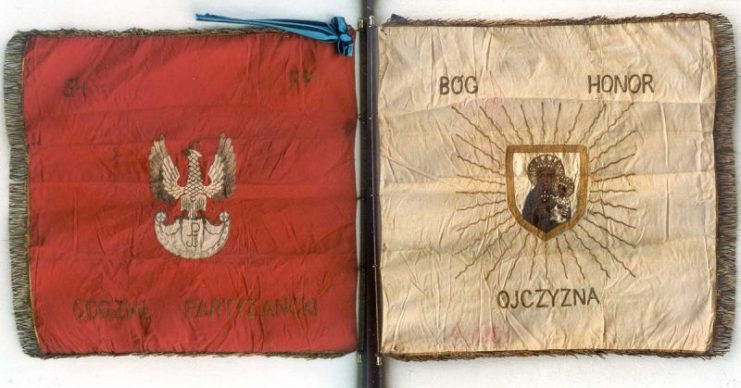

One of the most memorable events was a ceremony when the Partisan Unit of the 34rd Home Army Infantry Regiment received its own military banner. This event happened on June 29th in a forest near Jeziory village. The ceremony gathered not only partisans, but also many civilians from far and wide. Alfred Lea remembered: „I was very impressed to see the brass orchestra of a local volunteer firefighting unit marching down the road, playing Polish patriotic music, defying the Germans occupying this country. The Partisan Unit commander, „Zenon”, kneeled to take the banner from a representative of the Polish underground government. Then he marched the banner in front of all soldiers, and the religious part of the ceremony began. Firefighters and soldiers stood attention at the altar, and I still remember how the firefighters‘ helmets glared in the summer sunshine. The altar had a cross made of wood planks, and was draped with a USAAF parachute – this was our contribution to this monumental event.“ At the end of the ceremony, the Partisan Unit marched in front of ist commander, and the commanding officer of the 9th „Podlaska“ Home Army Infantry Division, General Ludwik Bittner „Halka”. The whole event was unthinkable to the Americans – it was so patriotic, religious, and spontaneous, and German units were not so far away! The picnic afterwards was limited as to the food, the German beer which had been “requisitioned” was weak and watery, but the vodka lived up to its fine reputation.

On another day, the partisans were assigned the task of blowing up a German supply training. 2 Americans, including Lea, participated in this mission. The mission was successful, and both Americans joined their Polish friends in a withdrawal to a rendez-vouz point. After blowing up the train, the partisans were on the move. To provide food for the troops, partisans stole a cow at night from a German-controlled farm. The hungry Poles and Americans led the cow to the regimental butcher, who did a quick work to distribute the meat to all soldiers. The silently moving partisans slipped right past a Luftwaffe air force base where some night fighters prepared to take off. It was strange for the Americans to be so close to the activity of their enemy and not be able to fight back. Finally, the regiment set up a camp in a forest, within eyesight of a village and the road passing through it. A partisan brought soap and water for the airmen, and they were given a shave. At this point, the Americans learned there would be a parade on the road to celebrate the Fourth of July. The village citizens came to watch the parade, and Gestapo (German secret police) learned about the event, as they were billeted just 2 miles away. 2 or 3 Germans came in a car, and they quickly saw they were outnumbered. They suggested a pardon to the Poles and an alliance with the Germans to fight the Soviets. This infuriated „Zenon“ who told them to go to hell, and slapped the German officer across the face. Partisans set fire to the car, and the Germans ran away.

On another day, the partisan regiment took positions on a forested hilltop overlooking a Luftwaffe airfield, and they monitored the air and ground traffic there for 48 hours. A Polish Air Force officer arrived unexpectedly with several operation manuals of Ju-88 German bombers (this type was stationed at the airfield). Plans were discussed to take control of the airfield long enough for Americans to steal 2 aircraft, which would be secretly fueled and armed by Polish forced laborers at the base. Courses were plotted to fly to Gdynia, Poland, then over the Baltic Sea and Denmark to England. Sweden was indicated as a potential destination if things would go wrong. The lead ship would carry the navigator, and the other one would have the bombardier. Ju-88 were 3 –seaters, so one person would need to fly in the bomb bay. Final analysis indicated 300 to 350 men would be needed to take and control the airfield, and cover the withdrawal. The Americans decided that too many Polish soldiers could die to make the escape worthwhile. Reluctantly, the Polish Home Army forces abandoned the plan which captured their imagination as the ultimate offense to the Nazis.

Another night, Americans were invited to a large mansion where they were treated to vodka, and saw the only electric refrigerator in the entire time they were in Poland. The refrigerator had the door open to let the cool air make more comfortable. After some small cakes, they were marched out into the forest to find a secret grass strip. Hooded flashlights stationed at the end of the runway could be seen. But the aircraft never turned up.

Every day, they could see German transport planes, the Ju-52s. The ones that were flying east carried fresh troops and supplies, and the Polish partisans developed successful tactics to combat those low-flying planes. The Ju-52s were referred to as „The Morning Express“, as they usually flew just after dawn. Lookouts would be positioned so that Poles would know which way the planes were coming. Some of the partisans rode horses, and they hid in hedgerows or under trees. When a Ju-52 would be close, they would ride out right under the plane, firing at the then with automatic weapons. Americans saw 4 of these airplanes shot down in this way.

While fighting in the partisan unit, Alfred Lea sustained an injury which earned him a Purple Heart. Al was assigned to drive an ammunition wagon, which was a 4-wheel, horse-drawn farm wagon with one horse. He had straw in it which covered the weapons and ammunition boxes. One day, the unit ran into a German army unit, and Poles had to retreat over some rough terrain. Al jumped off the wagon and started running along it. He wanted to stay low and not be a good target, as they were being fired at with machine guns. Al stumbled at some point, fell under the horse, and the horse stepped on Al’s leg, and fractured it. Luckily, it was a hairline fracture, but it swelled really bad. Al did not stop running, and he thought the leg was just badly bruised.

The life with the partisans was not always about fighting and evading German forces, and had its funny moments. One day they bathed in a small river, and they had to run nude for cover when strafed by a German fighter plane. Another day, Lea rode, dressed only in his underwear shorts, a bare-backed horse using only a rope bridle – he ended up going through the thorny branches of a plum trees orchard. The horse clearly did not understand English.

On July 27th, Polish partisans made contact with advancing Soviet troops. A Red Army colonel visited the unit, and promised to inform his headquarters about the airmen, and help them go to the US. The airmen were transferred to Soviet control the next day. „Zenon” demanded Russians to issue a document, confirming the Americans will travel safely to the US controlled airforce base at Poltava, Ukraine. The document was signed by the Soviet colonel and the American airmen: „We, undersigned below, are transferred today to the control of Red Army. Our hosts were partisans of the 34th Regiment of the Polish Army. We are all safe, fit, and healthy. The partisans took very good care of us, ensuring our safe return to the United States.”

Within several days, Alfred Lea and his friends went back to the 452nd Bomb Group base in Deopham Green, UK. When debriefed there from their adventures, all rescued airmen agreed that they would never be able to pay back what the Poles did for them, even if they worked for Poland their whole lives, regardless of risk or dangers.

After the war, the American crew received Polish Home Army Crosses. They were many more American airmen rescued by the Polish partisans in WWII, but only Alfred Lea and his colleagues were actual soldiers of the Polish Home Army.

A few facts for the historical context

On June 21st, 1944, the 8th Air Force flew its first „shuttle“ mission to the Soviet Union. Everything was top secret. The B-17s had extra fuel tanks installed in the bomb bay, reducing the available space and payload for bombs. The crews had special luggage – maintenance tools for P-51 Mustangs, and Class A dress uniforms which the crews had to change to before leaving the planes at the destination airfield. Some crews had even extra passengers – P-51 ground crews.

Alfred Lea and his crew belonged to the 452nd Bomb Group, and participated in this mission. Their unit flew over the North Sea and deep into Germany. The target for that day was the Schwarzheide synthetic fuel plant in Ruhland, north of Dresden, south of Berlin, but the 452nd Bomb Group attacked a target of opportunity at Elsterwerda. After bombing the target, the bombers continued east, into the eastern part of the Third Reich and into occupied Poland. The formation crossed the Soviet front lines and landed in a base in eastern Ukraine. The US forces would then use the bases in Ukraine to refuel and rearm the bombers. This arrangement with the Soviets opened the possibility for Americans to bomb any Nazi target in Europe.

Alfred Lea’s B-17 was shot down just minutes before reaching the Soviet front lines. 4 German fighter planes were claimed as destroyed. One US fighter plane was lost, and the pilot, Lt. Sibbett, was killed. He is resting at his original burial location in Miedzyrzecz Podlaski, Poland. His family decided after the war not to disturb his grave.

The German pilot who claimed the B-17 was Walter Wever from Jagdgeschwader 51. He scored 44 victories by the time he was killed on April 10th 1945. When I shared these details with Alfred in late 1990s, he said: “I hated him then, time heals all wounds and I pray that his death was swift and painless.”

The banner of the Partisan Unit of the 34th Infantry Regiment was hidden from Soviets later in 1944. It was hidden so well, that it was considered permanently lost until 2003, when it was found in a local church near Biała Podlaska, Poland. The banner is stored today in the Jasna Góra Monastery in Częstochowa, Poland.

Szymon Serwatka

The author, Szymon Serwatka, has been researching US Army Air Force over Poland in WWII for more than 20 years, and has been supporting the efforts to find American MIAs from WWII in Poland. He also offers WWII history tours to Poland, which include USAAF museum at Blechhammer and B-24 crash locations. Here is a link to The Blechhammer Tour

All photos provided by the author.