At the start of the American Revolution, shipbuilding grew in the Colonies because of raw materials and the many native white pine trees greater than 24 inches in diameter for ship masts. As subjects of England, the ships, guns and ammunition in America belonged to Britain.

George Washington, Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, called on volunteers for the army. Because the Continental Congress was not an official government organization, they could not charge taxes to raise money for a payroll or supplies (clothing, ammunition, food). At this time only a conviction of beliefs and the promise of future rewards could keep them in the military.

Men fought and women (wives, mothers and sweethearts) followed the men to cook for them, sew for them and in some cases to fight with them. What the patriots did not have was a Navy.

The British Navy was powerful; it was the oldest, largest and most experienced in the world. Even though in the years leading up to 1775 they had allowed some of their ships to fall into disrepair, they still had a fleet of 270 ships.

The advantage of their naval force meant the British could carry troops quicker by sea, bring supplies from England and their ships-of-the-line could sail into a harbor and attack cities or ports virtually unopposed.

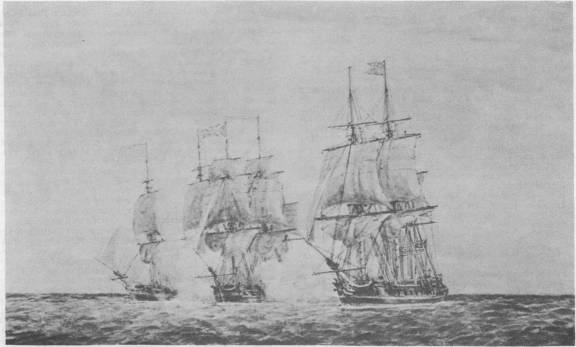

The ships making up the navy were masted-ships, they had sails and relied on wind, ocean currents and oars for rowing to move. The hulls (the body of the ship) were made of hard wood, and tall masts held the sails. The largest ships of the time were large warships (ships-of-the-line) holding as many as 100 guns. In order by size, other common ships used by navies were frigates, sloops and schooners. Other even smaller craft could have been used for carrying messages and spying.

In the spring of 1775, a group of patriots in Maine (then part of Massachusetts) led by Jeremiah O’Brien seized the sloop Unity and the schooner Margaretta from the British. O’Brien was given command of the Unity and he renamed the ship Machias Liberty and put it into service in the Massachusetts navy.

On October 30, 1775 the Continental Congress appointed a Naval committee that included John Adams from Massachusetts, Silas Deane from Connecticut, John Langdon from New Hampshire, Christopher Gadsden from South Carolina, Governor Stephen Hopkins of Rhode Island, Joseph Hewes from North Carolina and Richard Henry Lee from Virginia.

The representatives to the Continental Congress didn’t expect to develop a navy that rivaled Britain, with warships to do battle, they wanted support and annoyance. They needed fast transport and the ability to harass the British so they wouldn’t be able to use their navy in the coastal waters off the colonies.

The Continental Navy was expected to transport goods and people to battle areas. They also captured British ships to be sold to raise money to pay the crew and for the goods that the Continental army needed to fight the British.

Another important duty of the Continental Navy was to take representatives to other countries – like France, to gain support. On October 26, 1776 Captain Lambert Wickes sailed from Philadelphia to take Benjamin Franklin to France to negotiate a treaty. After dropping him off, Wickes was ordered to capture ships in the English Channel. He seized five and sold them in France to pay expenses.

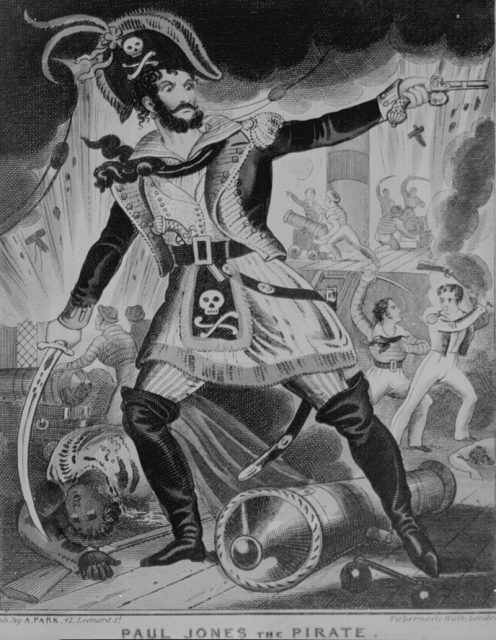

The American Revolution made heroes and one man especially excelled in naval warfare. John Paul Jones gained commission on the December 7, 1775 as a senior first lieutenant because Joseph Hewes of the Naval Committee wanted one of the commissions to go to a man from the South. John Paul Jones soon gained a command and developed a reputation of success.

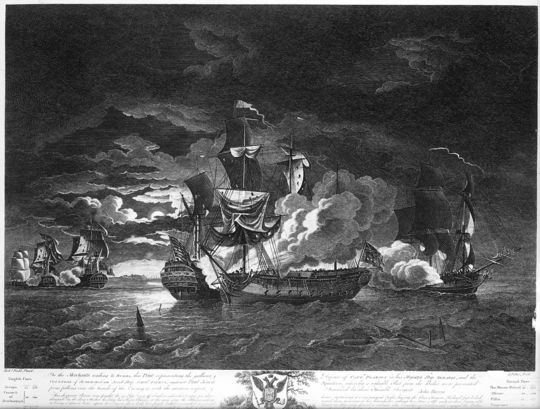

His most famous battle occurred when his ship, the Bonhomme Richard met the Serapis on September 23, 1779. After fighting began, the British captain asked Jones if he was ready to surrender as his ship was already damaged. Instead of surrendering, John Paul Jones said, “I have not yet begun to fight.”

The battle continued and with heavy losses on both sides until the commander of the Serapis actually surrendered. After the surrender, the Bonhomme Richard sank.

Despite successes, the Continental Navy was no longer in existence at the end of the War for Independence. They had sustained heavy losses, they had a force of 27 ships in 1776 and at the end of the war, only one ship remained which they sold to pay debts.

The American navy while ingenious and courageous was never really a match for the British. It was more an irritant, but over the next several decades the need to develop a proficient navy would drive the young nation to build it’s own naval tradition that continues today.