As far back as anyone who is alive today can remember, relations between the United States and Canada have been peaceful and friendly; the two countries enjoy amicable cooperation along their cumulative 5,525 mile long border.

But cast your mind back to the end of the American Revolution and the first few decades of the 1800s, and the picture is vastly different, full of struggles for control over frontier territory and trade routes.

During the War of 1812, the American army took control of Fort Amherstburg in present-day Ontario, renamed it Fort Malden, and held it until February 1815; Parks Canada describes this key fort as “the site of the longest American occupation on Canadian soil.”

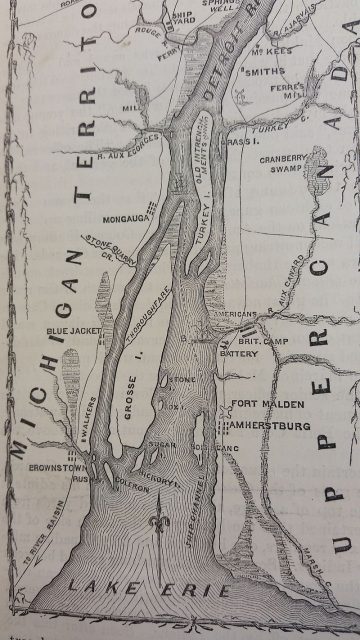

Prior to the War of 1812, occupation of the “Northwest Territory” was a matter of dispute. The British were supposed to cede Detroit and its fortifications after the end of the American Revolution but did not. After Jay’s Treaty went into effect in 1796, the British were finally forced to leave—whereupon they crossed the river and promptly began construction on Fort Amherstburg.

This fort, completed in 1804, is described by The Canadian Encyclopedia as having four diamond shaped corners with four cannons each, a 2,952 foot long perimeter, a dry ditch, and a ravelin (earthen embankment) along with four more cannons that helped protect the main gate.

The British wished to protect their interests in the Great Lakes area by building a fort that would command oversight on Lake Erie and the Detroit River, for land routes into Canada were few, making control of the Great Lakes vital to facilitating trade and communications.

Some Americans chomped at the idea of annexing Canada for the United States, an idea that would not be fully dropped until the Rebellions of 1837 and 1838 were subdued. The King’s Navy Yard, protected by the fort, ensured the British maintained naval superiority, and the fort itself doubled as the “Indian Department” headquarters.

In 1812, as tensions between Great Britain and the United States began to mount toward war, American General William Hull and his Northwestern Army of over 2,000 men marched overland toward Detroit to protect that vital settlement. Foolishly (in hindsight), Hull hired the schooner Cuyahoga to carry the majority of his baggage, despite the fact that the ship would have to pass Fort Amherstburg in the British-controlled waters.

While Hull and his army laboriously cut a road through the Ohio wilderness, the British at Fort Amherstburg received official notice of the declaration of war—and scored their first “victory” of the war by seizing the unsuspecting Cuyahoga. Among Hull’s baggage they found a gold mine: the general’s private papers, full of useful military information.

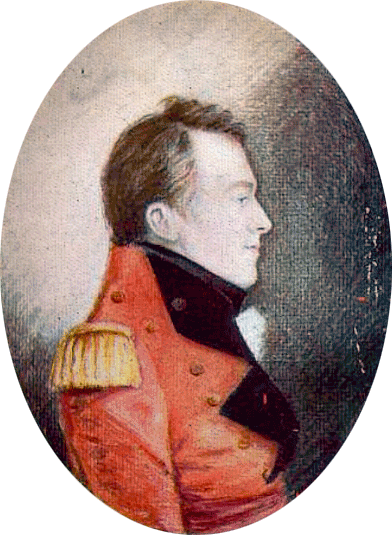

Fort Amherstburg also would soon be the site where two great military figures would meet and famously collaborate to seize Detroit and re-annex Michigan Territory to Canada. One of them was Major General Isaac Brock, governor of “Upper Canada”.

Brock chose Fort Amherstburg as his headquarters because, according to author Harry L. Coles in his book The War of 1812, Brock realized the “essential elements” of the British position were maintaining naval control of the lakes, his supply chain, and gaining full cooperation from the local Native Americans and militia. Amherstburg was where all of those factors intersected.

The British had been successfully harassing General Hull’s supply lines, and now Brock wanted to take the action a step further by attacking Detroit. He was greatly aided in his plans by the military intelligence gleaned from Hull’s papers on the Cuyahoga.

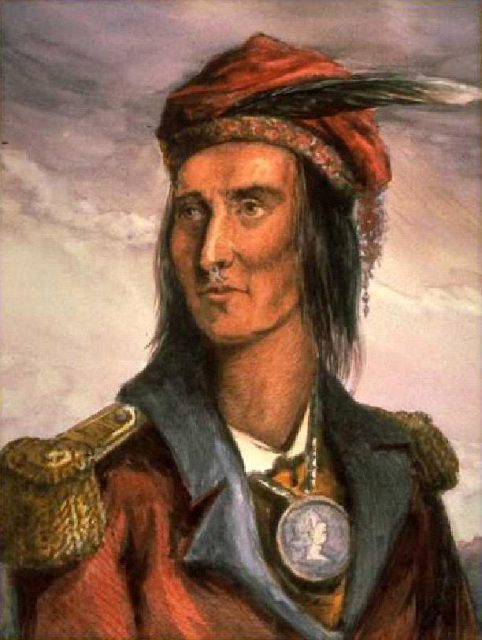

The other legendary figure to collaborate at Fort Amherstburg was the great Shawnee Nation chief, Tecumseh. Brock warmly wrote, “Tecumseh…for the last two years had carried on, contrary to our remonstrances, an active warfare against the United States. A more sagacious and gallant warrior does not exist. He was the admiration of everyone who conversed with him.”

Brock’s favorable first impression was heartily returned; Brock gained Tecumseh’s respect for his bold plan to immediately attack Detroit, and an alliance was formed.

Joining forces with Native Americans was vital to the success of Brock’s plan because the British government, preoccupied with fighting Napoleon in Europe, took the attitude that Canada needed to mostly fend for itself. Unable to get full support from England, the Canadians relied on Native Americans to increase their fighting strength. Tecumseh’s men nearly doubled Brock’s available manpower.

Unlike Brock and Tecumseh, General Hull was hampered by his own timidity and pessimism. Had he attacked the weakly defended Fort Amherstburg as soon as he reached Detroit, he probably could have taken it fairly easily; but he delayed his proposed assault for so long, the British had time to reinforce it. Hull finally crossed the river and briefly occupied Sandwich nearby, but quickly withdrew without going on to attack the fort as planned.

He thought the British forces were much larger than they really were, and was disheartened to the point of paralysis by multiple ambushes on his supply lines. When he learned that Fort Michilimackinac to the north had fallen, he began to panic at the prospect of an “Indian massacre” from that direction.

On August 15, 1812, Brock, Tecumseh, and their 700 British and 600 Native American forces crossed the Detroit River while the British began bombarding Fort Detroit—in part from gunboats that had been built at King’s Navy Yard, as well as from shore batteries recently installed at Sandwich, virtually under the noses of the Americans who had abandoned it.

Hull’s stress over the Native American presence was not helped by Brock’s demand for surrender that pointedly said Brock would not have control over the actions of the natives in the event of a battle. Without firing a shot in defense, Hull surrendered his 2,500 man army rather than risk the fight.

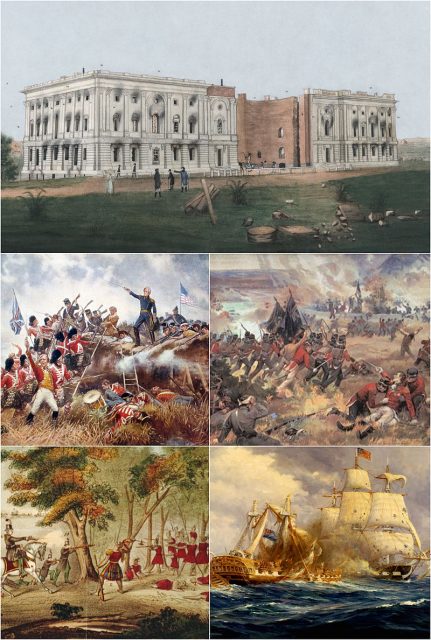

The uncontested loss of Detroit was a humiliating blow to American pride, and the public cried out for vengeance. Unfortunately, it would be another year before vengeance came, and in the meantime, General Brock was killed.

His replacement at Fort Amherstburg was General Henry Procter, and minor battles and skirmishes continued to keep the occupants of Fort Amherstburg busy. Included in these were the River Raisin battle (which famously led to a massacre of the wounded American prisoners afterward) and two unsuccessful offensives against the Americans at Fort Meigs.

Failing to take Fort Meigs, Procter went looking for a quick victory with which to impress his Native American allies, and picked Fort Stephenson, which held only about 160 soldiers who were commanded by 23 year old Major George Croghan.

Ordered to evacuate the fort instead of fighting the far superior British force, Croghan’s response was “We have determined to maintain this place, and by Heaven, we will.” With only one piece of artillery and his Kentucky sharpshooters, Croghan indeed held the fort against the British assault, which ended the British offensive in the Great Lakes area.

In the end, it was not the United States’ second Northwestern Army but a nine-ship inland navy that would not only redeem the loss of Detroit but also end British naval superiority in the Great Lakes and cause the British to abandon Fort Amherstburg.

Built at Erie, Pennsylvania, and ably commanded by Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry, the American fleet sneaked past the British blockade and began putting the pinch on Fort Amherstburg’s supply lines. This created a desperate situation of dwindling supplies and short rations at the fort.

Just as British harassment of General Hull’s supply lines directly affected Hull’s decisions and led to the surrender of Detroit, American naval interference with Fort Amherstburg’s supply lines directly affected General Procter’s decision to send the outnumbered British ships to look for the pesky American fleet, which led to the disastrous British defeat at the Battle of Lake Erie.

When General Proctor learned the outcome of the battle, he wrote, “The loss of the fleet is a most calamitous circumstance. I do not see the least chance of occupying to advantage my present position, which can be so easily turned by means of the entire command of the waters here which the enemy now has.” In fact, the fort’s armament had been stripped in order to arm the British schooner Detroit, the last British warship to be constructed in the navy yard and now in the hands of the Americans.

Accordingly, Proctor abandoned the fort and town, setting everything on fire. When the Americans marched into Amherstburg on September 27, 1813, they found it in ruins. Appreciating the strategic importance of the site, they began building a new fortification, naming it Fort Malden, and occupied the area until the Treaty of Ghent ended the war and returned Fort Malden and the surrounding area to the British.