M75

During World War II, it became increasingly clear that infantry would need mobile, protective transport vehicles to carry them to and around battlefields. In a world of armored warfare, it was not enough for them to be brought up in trucks and then slog their way forward on foot.

Some efforts were made to get around this during the war, but it was in the aftermath that armored personnel carriers (APCs) began to emerge.

In September 1945, just as the war was ending, the US Army put out a new specification to the manufacturers of military vehicles. It was looking for a personnel carrier, fully enclosed to protect the men inside and tracked for cross-country travel.

Seven years later, the M75 APC entered service. Like many APCs, it was developed using components from existing vehicles, in this case the running gear from the M41 light tank.

The hull mostly consisted of a large steel box, with twin doors at the rear through which ten infantrymen could embark. The driver sat at the front beside the engine, and the commander sat behind him with a cupola and .50 caliber machine gun.

The M75 did not have an amphibious capability, an increasingly important feature in post-war fighting vehicles. Due to changing demands and understanding of modern warfare, it was already showing its flaws by the time it reached the Army. But as a proof of concept, it moved the US military forward.

Built in small numbers using components from tanks, the M75 was also not cost-effective. The Army soon began looking around for a better option.

M59

Introduced in 1953, only a year after the M75, the M59 was its replacement. Learning from their experience with that first APC, designers incorporated features such as amphibious systems and a lower profile.

In many ways, the M59 looked like the M75. It was little more than a steel box with a sloped front, carried along on tracks. The driver again sat at the front, between the engines, with the commander nearby in a cupola that carried a .50 caliber machine gun and periscopes for safely viewing the surrounding area.

But the overall design was cleaner than its predecessor, and it was less vulnerable to enemy fire. A hydraulic ramp at the rear and two hatches in the roof gave infantry multiple ways in and out of the vehicle.

The M59 was successful enough to be mass produced and turned into several variants. These included a command vehicle, a mortar carrier, and an ambulance.

The M5 had one critical flaw. Its engines were underpowered relative to the demands placed upon them, leading to heavy wear. That affected its reliability and placed a hefty burden on maintenance teams. The drawback was outweighed by its advantages, however, as it was both better and cheaper than the M75. It remained in service for decades.

M113

As the technology and doctrines of war developed during the Cold War, demand emerged for another sort of APC, one light enough to be transported by air. The M59 and M75 were both too heavy for this, so the US Army put out another specification for an APC light enough to be carried by aircraft.

In 1960, the resulting machine started to roll off the assembly lines and into infantry divisions. This was the M113 APC.

At first glance, the M113 looked a lot like its predecessors: little more than a rectangular metal box on tracks with a sloped front. But under that shell, it was a more sophisticated vehicle.

Critically, it was built out of aluminum rather than steel, making it significantly lighter but still tough enough to protect the men inside.

Once again, the driver and engine were installed at the front. The commander’s cupola was mounted in the center of the vehicle, again equipped with a machine gun and devices to let him see out.

Around him, ten infantrymen sat along the walls. They could get in and out through a hydraulic ramp at the back or a hatch above their heads. The vehicle could become amphibious with little preparation, using its tracks for propulsion.

Initially equipped with a petrol engine, the M113 switched to diesel in 1963 with the M113A1 model. It was also modified into a wide range of variants, carrying everything from specialist radar to missiles to bridge-laying equipment. Tens of thousands were made and sold around the world.

Bradley M2

As the 1960s progressed, expectations for transport vehicles changed. The potential for war against the Soviet Union brought with it the fear of nuclear, biological, and chemical contaminants (NBC) as well as the need for fast, tough vehicles that could take part in fighting.

The appearance of the Soviet BMP series of vehicles made the case more urgent and set the US on a course towards its first infantry fighting vehicle (IFV).

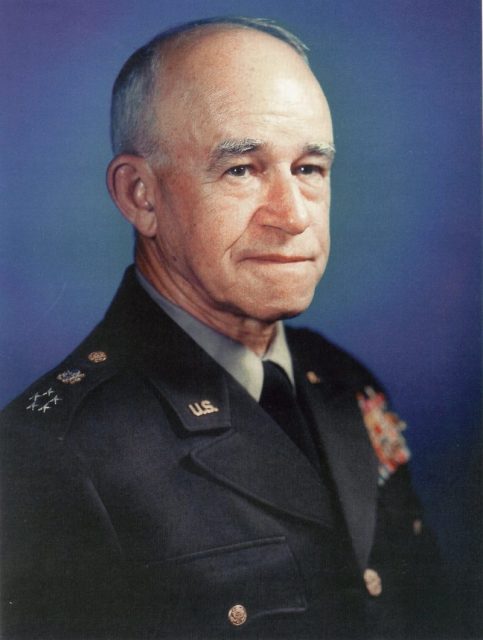

It took over a decade of changing specifications, with political battles over design and budget, before the resulting vehicle finally appeared in 1981. Named after WWII general Omar Bradley, the Bradley Fighting Vehicle came in two forms.

The M3 Cavalry Fighting Vehicle was an anti-tank weapon, carrying missiles and a two-man scouting team. Using the same chassis, the M2 Infantry Fighting Vehicle carried a six-man infantry squad and was the latest development in US armored troop transports.

The Bradley kept many of the basic features of preceding transports, including tracked propulsion and a front-mounted engine with infantry in the rear. It was equipped with a small turret, carrying an M242 25mm chain gun and a coaxial machine gun. It had solid aluminum armor, NBC protection, excellent mobility on land, and amphibious capability.

Read another story from us: From Mice to Elephants – The Amazing 5 Years of WWII Vehicle Development

Several attempts have been made to find a successor to the Bradley, so far without success. This Cold War creation remains a vital part of the US military to this day.