Oskar Schindler is credited with saving about 1,200 Jews during WWII, but he was not alone. Another person would outdo Schindler, despite his unusual background.

Although officially neutral in WWII, Spain had a rather cozy relationship with Nazi Germany as both countries shared the same Fascist ideals. Fortunately, not all who served in the Spanish Government shared those views.

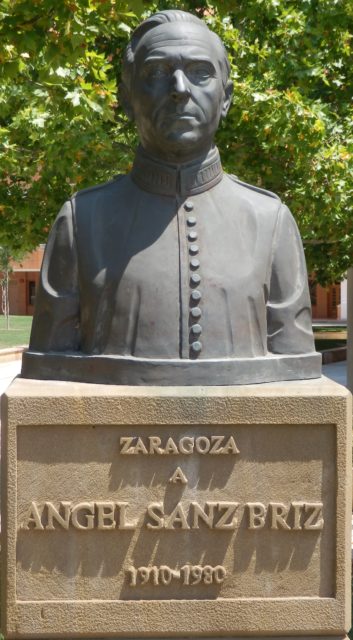

Ángel Sanz-Briz was born on September 28, 1910, in Zaragoza, Spain to a family of wealthy merchants. He studied law and acquired a degree in Diplomacy in 1936 – the year the Spanish Civil War broke out.

A conservative, he fought with General Francisco Franco Bahamonde. With help from Nazi Germany, the rebels were defeated, and Franco took control of the Spanish Government. Sanz-Briz was rewarded with a job at the Spanish Legation in Egypt and then in 1942 was appointed the Chargé d’Affaires in Hungary.

Four years earlier, Hungary had enacted a series of anti-Semitic policies. Among other restrictions Jews were banned from public office, their numbers were limited in certain professions, and they were denied the vote. Then in 1940, the country allied with Germany and began forcing Jews and other minorities to work in labor camps.

Although the full extent of the Holocaust would not be known until after the war, the fate of Hungarian Jews became international headlines in the early 1940s. Fortunately, the Hungarian Government did not send their Jews to concentration camps in Poland as Germany was demanding.

That changed when Germany invaded Hungary on March 19, 1944. What little protection Hungarian Jews enjoyed was gone. SS Lieutenant Colonel Otto Adolf Eichmann was given command of enacting the Final Solution of the Jews. Those in the countryside were sent to camps, while those in Budapest were put in ghettoes pending expulsion.

The Arrow Cross Party were now the new Hungarian Government. Virulently anti-Semitic, they were willing and enthusiastic participants in Nazi atrocities. To save ammo, they lined people up along the Danube River and tied them together. When they shot one, the other would fall with them and drown.

Sanz-Briz and many others could no longer stand by and do nothing. He appealed to his government for help, but while Spain was not anti-Semitic, neither were they sympathetic to the plight of Hungary’s Jews. However, Secretary of Foreign Policy, José Félix de Lequerica, urged Sanz-Briz to do what he could; as long as he did it legally.

Fortunately, the Spanish Constitution of 1924 decreed that all European Sephardic Jews were entitled to Spanish citizenship. Sephardim are descendants of Jews who had lived in the Iberian Peninsula since the 2nd millennium. The law was invoked to make amends for their expulsion in the 15th century.

Under this law, Spanish Embassy staff were able to get out about 500 people from the Jewish ghetto openly. Declared to be citizens of a friendly country, those Jews could then stay in Budapest free from harassment, or they could go to Spain if they could afford to. The Spanish Government issued some 200,000 visas all over Europe until Germany protested.

The Sephardim taken care of, Sanz-Briz was given only 200 more visas to hand out. Unfortunately, the vast majority of Hungarian Jews were Ashkenazi (northern European Jews). He hatched a plan.

Working with other diplomats and businessmen, he rented houses and apartments throughout Budapest and declared them to be Spanish territory. Ashkenazis braving the trip to the Spanish Legation on Eötvös Street asked for visas.

They would be housed and provided with food, so they did not need to venture out and be caught. Those who could afford to leave the country did. This worked until Nazi and Arrow Cross soldiers inspected the visas more thoroughly and started questioning their validity. Sanz-Briz came up with a new plan.

With only 200 visas, he began adding letter sequences to them. If someone got Visa #1, he would give the next person Visa #1-A, and so on. Sanz-Briz extended single visas to cover entire families. A person with a permit declared someone else to be their brother/sister, son/daughter, uncle/aunt, etc., and those people were covered. As long as the visa number did not exceed 200, he could keep it up.

About 700,000 Jews were still in the ghetto – their numbers only dwindling when trains came to deport them. Others died from hunger and malnutrition.

As the tide of war turned against the Axis powers (those allied with Germany), travel to Spain or anywhere else was no longer an option for most. This meant Sanz-Briz needed to rent more and more safe houses for Jews and provide them with food. They were taught basic Spanish so they could try to pass off as Spanish nationals.

By late 1944, the Red Army was just outside Budapest, so the Spanish Government ordered Sanz-Briz to leave for Austria – believing it would be safer for him. He left on December 20, but not before making arrangements for his work to persist.

Giorgio Perlasca, an Italian Fascist who supported Franco, unofficially took over the Spanish Legation. Fortunately for the Jews, Perlasca had a change of heart regarding Fascism. He continued San-Briz’s work.

With the Chargé d’Affaires gone, the Hungarian Government ordered the Legation to clear out its Jewish population. Perlasca bought time by claiming that San-Briz was going to return shortly. He continued moving Jews to safe houses, while other embassies took in more.

It is believed San-Briz may have saved some 5,200 Jews during his time in Budapest. After the war, he became an ambassador to other countries, but rarely spoke about what he did – not even to his family. As Spain wanted to distance itself from its previous association with Nazi Germany, history would credit Perlasca for what San-Briz started.

In 1991 Yad Vashem (Israel’s Holocaust Museum) recognized the former Spanish Ambassador as one of the Righteous Among the Nations – eleven years after his death. They called him the “Angel of Budapest” after that.