Flora Sandes was born on January 22, 1876, in Nether Poppleton, Yorkshire, England to a pastor. Fortunately, he was a liberal man, as Flora often complained about being born as a woman. When she was nine, the family moved to Suffolk. She was an oddity among her peers; not interested in dolls and sewing. She preferred horseback riding and shooting – activities made possible because of a rich uncle.

Inspired by Lord Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” her favorite fantasy was being a soldier on horseback attacking Russian troops in the Crimea. She could not have known how prophetic that was.

Her uncle’s generosity allowed her to train as a secretary when she was 18 and also enabled her to learn to fence. She later worked in Egypt, Canada, and the US where she shot a man. It was in self-defense and the man survived. In future, however, others would not be so lucky.

Sandes eventually returned to London where she bought a racing car and joined a shooting club. In 1907, the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry was set up – an independent all-female charity training women in nursing. The thirty-one-year-old Sandes signed up, but she was not satisfied for long as she saw little action.

Three years later she left the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry to join an American version called the Women’s Sick & Wounded Convoy. They saw action during the First Balkan War in 1912, doing what they could in Serbia and Bulgaria. In 1914, Sandes was back in Britain where she volunteered to become a nurse but was rejected.

Sandes was now, practically a social outcast. Thirty-eight, single, and living with her widowed father. She kept her hair short, was overly fond of cigarettes and alcohol, knew nothing of housekeeping, and did not care. “Unladylike” was the term used then.

Then WWI broke out in July 1914. She joined the St. John Ambulance unit – a team of 36 women set up by an American nurse. By August, they were in the town of Kragujevac, Serbia which was barely holding its own against the Austro-Hungarian offensive.

At first, unable to speak to her patients, she managed by using sign language. By late 1915 she had learned Serbian enough to qualify her for the Serbian Red Cross. Assigned to the 2nd Infantry Regiment (also called the “Iron Regiment” due to their legendary courage) of the Serbian Army, she was put right on the front line.

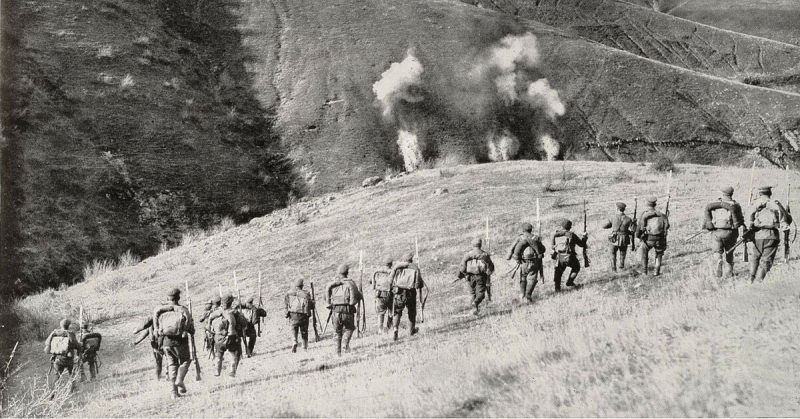

On October 7, the Austro-Hungarians and their German allies crossed the Drina and Sava Rivers toward the city of Belgrade, which fell two days later. The Bulgarians attacked on October 14, defeating the Serbian Second Army at the Battle of Moravia. The latter were forced to retreat to the Adriatic through Montenegro and Albania.

Tens of thousands of Serbian civilians fled with their forces despite the lack of food, supplies, and barely passable roads. It was the worst possible weather. What cold, hunger, disease, and enemy forces failed to do, Albanian tribal bands did. Many did not make it.

In the chaos that ensued, Sandes got separated from her group. Her Red Cross armband protected her, but everyone else was fair game. Furious, she ripped it off and demanded to join the 2nd Regiment as a private so they would give her a gun and food.

Women had long fought in the Serbian Army, but they were usually Serbs. Sandes was the first British woman to do so. She was no shrinking violet, finally living out her fantasies – although not against the Russians. She fought with such gusto; they promoted her to the rank of sergeant within a year.

In September 1916, French and Serbian forces launched the Monastir Offensive against the Bulgarians. Sandes was in a group fighting their way to the town of Monastir on November 16. A grenade blew her backward pummeling the right side of her body with 28 shrapnel wounds and shattering her arm.

She spent two months in a hospital and received the Order of the Star of Karađorđe – Serbia’s highest award. She was made a Sergeant Major and then sent to England for further treatment.

While convalescing, Sandes wrote her autobiography, An English Woman-Sergeant in the Serbian Army. Money earned from it went to Serbian soldiers. She returned to Serbia in May 1917. No longer able to fight, she ran a hospital and continued fundraising for Serbian troops.

WWI ended for Serbia on November 3, 1918. Sandes stayed on as a commissioned officer with her own platoon. In October 1922 the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (precursor of Yugoslavia) significantly reduced its military. Sandes was out of a job, although she did get a pension.

In 1927 she married a Russian colonel who had escaped the Bolshevik Revolution to fight for the Serbs. They lived in Britain and France, before returning to Belgrade where Sandes earned a living by driving that city’s first taxicab. She also wrote her second book, taught English, and gave lectures about her experiences around the world.

They were in Belgrade when WWII broke out, so she was urged to leave for Britain. She refused, of course. The Yugoslavian military asked the 65-year-old Sandes and her husband to return to military service, and they complied. However, Germany invaded in April 1941.

The Gestapo chucked her in prison as an enemy alien before releasing her on parole with one condition – that she report to them on a weekly basis. Shortly after, her husband died of heart failure, leaving her alone in Belgrade until the end of the war.

Sandes then moved to Zimbabwe to live with her nephew. Within a few months, however, the authorities asked her to leave. Her crime? Fraternizing with the natives.

Sandes returned to Suffolk. In 1956 she renewed her passport intent on yet another adventure. Sadly, she passed away before she could use it – but what a life she lived.