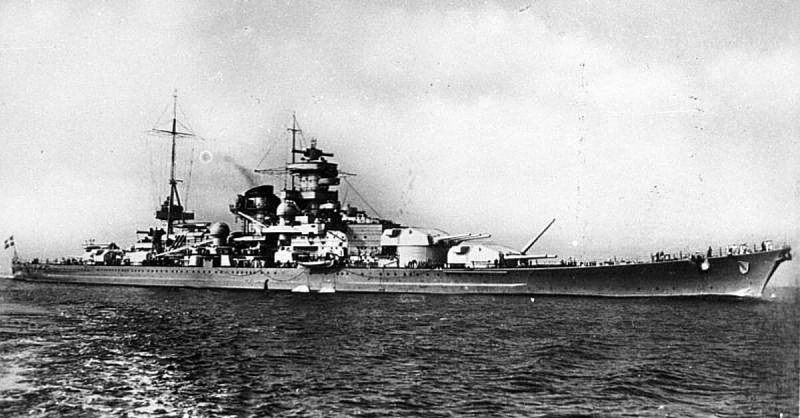

It was wholly dark. In the sea north of Tromsø in Norway, the great German battleship Scharnhorst was on a mission to sink an Allied supply convoy bound for Russia.

Unknown to the German command, the convoy’s British escort, led by Admiral Sir Robert Burnett and Admiral Bruce Fraser, had successfully intercepted the Scharnhorst’s radio communications. They were fully aware of the Scharnhorst’s plan to sink the convoy.

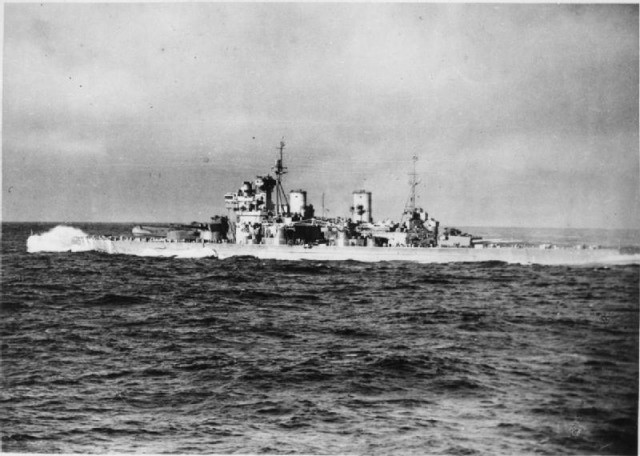

It was the day after Christmas. On the north sea, December 26th, total darkness reigned for most of the day. The British Admiral Fraser commanded from the HMS Duke of York, a powerful and heavily armed battleship. Supporting the Duke of York were the Cruiser Jamaica and four destroyers.

Admiral Burnett had three cruisers under his command, HMS Sheffield, HMS Belfast, and HMS Norfolk.

In preparation for the attack, Scharnhorst had been placed in a position of readiness, on the path of the convoy. Admiral Burnett was aware of her position and put his three ships between the convoy and the expected direction of attack. Admiral Fraser, meanwhile, maneuvered his command to the southwest of Scharnhorst’s position, to block her escape.

The Scharnhorst had was accompanied by five destroyers. Her commander, Konteradmiral Erich Bey, now arrayed these in a line in front of Scharnhorst, screening her as he prepared to engage the convoy. The order to go to battle stations barked out over the Scharnhorst’s loudspeakers, and her crew of almost two thousand men prepared for the assault.

The German command was completely unaware of the presence of the British fleet. In an attempt to avoid detection, the radar systems on the Scharnhorst had been turned off. When the thunder of the Belfast’s first salvo tore through the darkness, it was a complete surprise. Minutes later, the Norfolk engaged. In this initial engagement, the Scharnhorst suffered two direct hits.

She returns fire from the hindmost of her three massive gun turrets, but with little effect. Her forward radar capability had been destroyed, and she immediately increased her speed and attempted to disengage from the British cruisers.

The maneuver failed. British radar capability was well advanced in comparison to Germany, and an hour after the first exchange of fire the Belfast had picked up Scharnhorst in a position to the northwest of the convoy. The three cruisers immediately closed with the Scharnhorst and began to fire.

Scharnhorst had been equipped with two radar systems, one fore, one aft. The forward radar was in pieces, but the aft radar picked up the British ships, and Scharnhorst returned fire at their position from all three of her gun batteries. In the darkness, the cruiser Norfolk took two direct hits.

Another turn, another increase in speed. The Scharnhorst, still intent on her mission, attempted again to escape the destroyers and find the convoy. Admiral Burnett backed off with his damaged cruisers but kept the Scharnhorst in the sights of his radar. Admiral Fraser began to move toward the rest of the fleet with the HMS Duke of York.

After some time searching unsuccessfully for her target, the Scharnhorst gave up the chase. The screen of destroyers was dismissed, and the Scharnhorst set course for her base in occupied Norway. But the British were not so easily put off.

HMS Duke of York picked up the Scharnhorst on radar and began to follow her. Half an hour later Belfast came within range and lit up the darkness with a volley of star shells. Their glaring light showed up the great bulk of the German battleship, alone now that her screen of destroyers had been sent back to port, and the Duke of York immediately began the bombardment.

Within ten minutes of opening fire, the Scharnhorst’s forward gun turret was completely disabled. Within half an hour, the turret had taken two more direct hits. The Scharnhorst was on fire, and the crew were forced to flood the forward magazine in a desperate attempt to avoid a crippling explosion. The next hit punched through the Scharnhorst on her starboard side and exploded in the foremost of her three boiler rooms. Her engines now crippled and her forward gun turret destroyed, the Scharnhorst began to flee.

In the damaged boiler room, the crew worked frantically to repair the damage. The repairs allowed her to increase her speed somewhat, and she rained shell fire on the Duke of York from her aft gun battery as she made haste to escape the battle. The Duke of York‘s firing radar was damaged, and Admiral Fraser pulled his damaged ship back and gave the order to cease fire.

Two of Fraser’s four destroyers were ordered to close in for the kill, and they did so, firing a volley of torpedoes after the limping Scharnhorst. She took four direct hits along her length, and slowed to only twelve knots, a fraction of her normal speed. She had put some distance between her and the Duke of York, but seeing how the Scharnhorst was now placed, Admiral Fraser gave the order for his Battleship to close in again.

On the Scharnhorst, the remaining crew were ordered to attempt the retrieval of ammunition from the crippled forward turrets. There was an air of terror and desperation as they ran back and forth, the aft gun turret being now their only hope of self-defence against the onslaught of the British. Their efforts were in vain. The cruisers Jamaica and Belfast closed ahead of the Duke of York, and their torpedoes had little difficulty finding their mark.

The Scharnhorst began to list to starboard. Admiral Fraser gave the order to withdraw some short distance, and at 19.45 hours the Scharnhorst’s bows sank under the water. Steam and smoke gushed from the holes in her armor as the freezing north sea poured in to claim her. She disappeared under the waves.

In the darkness, the British ships moved in to attempt a rescue, but in all, less than forty of the Scharnhorst’s crew of 1968 were saved that night from the cold, black waters of the North Sea.