Buried thirty feet underneath the ground, in the basement of an old convent in southern Poland, is a room which used to be the secret bunker of a Nazi villain in World War II. From the confines of this room were issued orders which would see the end of many Polish and Jewish people.

However, after the end of the war in 1945, the existence of this room would somehow be swept under the rug and remain largely unknown until 2016. It is at last known that this room in the days of the war was the secret bunker of Fritz Bracht, also known as the “Beast of Auschwitz.”

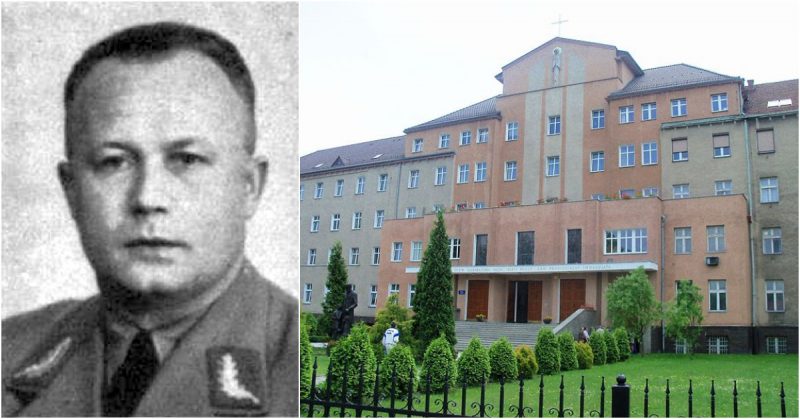

Fritz Bracht, born on January 18, 1899, in Heiden, Germany, was a man who grew from a lowly gardener into a highly respected commander in the German military. He would fly through the ranks, leaving behind him a reputation for ruthlessness and loyalty to Nazi ideals.

It was his devotion to Hitler’s cause, at the expense of the Poles and Jews that became his victims, that earned him the sobriquet Beast of Auschwitz.

To Nazi Germany and Hitler, he was an outstanding devotee who would stop at nothing to put his country on the map. To the Allies and the prisoners that felt his wrath up close, he was a monster who deserved a place in the scorching fires of hell.

Fritz Bracht’s journey toward becoming the Beast of Auschwitz began when he left his work as a gardener to enroll in the German military during World War I. The war was a stint that did not end well for him, for he was captured by British soldiers and held prisoner until 1919.

After the war, he worked for some time as a handyman before joining the Nazi Party on April 1, 1927. He fit in so well with the principles of the party that he was quickly promoted to the position of Deputy to the Reichstag. He followed that up with winning an election as the Prussian Landtag and becoming the acting Gauleiter of Silesia.

Then he served under Gauleiter Josef Wagner, the district governor of Silesia who, for his connection to Catholicism, fell out of favor with Hitler. After Wagner was ejected from the party, Silesia was split into Upper and Lower Silesia regions, with Bracht being appointed the new Gauleiter of Upper Silesia.

Bracht quickly set to work in enforcing a program that involved deporting or imprisoning people who were not considered “German enough.” It earned Bracht a nickname among the locals: “Kokot,” which was, well, not a very pleasant thing to call a person.

Bracht continued on his way up the ladder, becoming the Reich Defense Commissar of his region.

He met with one of his idols, Heinrich Himmler, in the months that followed. He spent just forty minutes with Himmler as they inspected Auschwitz together.

At the time, Auschwitz held a little over 10,000 captives. Himmler’s visit would result in the expansion of the death camp into a nearby village, which would come to be known as Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

Bracht’s devotion to the Nazis’ cause had put the spotlight on him. Hitler’s propaganda chief, Joseph Goebbels, publicly stated his admiration for Bracht, calling him “one of the best.”

In 1944 Bracht received another promotion, becoming an Obergruppenführer in the Nazis’ original paramilitary Sturmabteilung. This rank brought Auschwitz-Birkenau under his direct jurisdiction.

Throughout Bracht’s career, most of his time had been taken up with building extermination camps, directing their affairs, and adding more prisoners to these camps. Shortly after his promotion to this recent position, the Allied Forces turned their attention towards Silesia. Silesia was particularly targeted for bombing because of its oil refineries.

This Allied onslaught would force Bracht to begin looking for a new, safer place to make his headquarters. The search for a new command post did not last long as Bracht’s sights were immediately set on a building close to the center of Katowice: the convent belonging to the Sisters’ Servants of Silesia. Bracht immediately seized this building without any consideration for its former occupants.

Bracht’s new command center was safe and well-hidden, tucked in a basement thirty feet underneath the ground. Being in a convent set in the less industrialized part of the city made for an efficient disguise.

The command post boasted a trap door as the access point, escape routes, a bombproof ceiling that was 3 feet thick, and cell doors.

The features of the headquarters were published in a newspaper article captioned “In the Command Post of the Gauleiter,” written to boost the morale of the German people. It tried to depict the daily activities happening within the command post and painted it in a very favorable light to show the German people that everything was “under control.”

Although the real actions that occurred behind the walls of the command post remained unknown to the locals, the convent still drew wide local attention. The important men that came and left and the heavily armed guards stationed all around the convent caused people to call it the Gauleiter Haus.

As 1944 neared its end, Soviet forces pushed their boots deeper into German-held Poland and headed for Krakow and Auschwitz. In light of this, several German officers were desperate to conceal all that had occurred in the death camps.

Bracht instructed that prisoners be prepared for a long journey away from their extermination camps in Poland and into Germany. Those considered unfit for the long trek to Wodzislaw Slaski on the Czech border were killed.

This order resulted in the movement of 50,000 prisoners through 40 miles to Wodzislaw, where a freight train was waiting. Thousands lost their lives in the freezing winter cold along the way. Those that survived were loaded onto trains and sent on their way to the extermination camps in Mauthausen and Buchenwald.

Seeing the way the war was going, Bracht and his wife fled from Katowice to Kudowa, a place at the bottom of the Stalker Mountains. On May 9, 1945, unwilling to face capture and justice for his crimes, Bracht committed suicide by taking cyanide and made his wife do the same.

After the war, the convent Sisters turned the bunker into an underground storage room, erasing most of its history and all evidence pointing to the horrendous deeds orchestrated within its walls.

However, 71 years later in May 2016, a journalist named Tomasz Borowka and an author named Dr. Miroslav Wecki caught on to traces of evidence that led to the discovery of the secret lair.

This place has in fact, never been a complete secret, owing to the fact that the Sisters continued to make use of it even with probable knowledge of what the bunker had been used for.

Read another story from us: Drone Reveals Auschwitz Inner Horrors

To the rest of the world, though, the Bunker had been a place unknown. With Borowka and Wecki’s discovery, a path to a new piece of history was created.

However, the Sisters were not ready to let their convent get feasted upon by the raging curiosities of the world.