Before his time defending Petersburg from Union forces, Rebel General Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard learned how to command, strategize, and organize armies during the Mexican-American War. Due to observing those around him and participating in councils of war, he would later become a prominent general like those with whom he served in Mexico.

Born to a Catholic family on a sugar plantation in Louisiana, Beauregard hailed from Creole stock. While attending school in New York as a boy, he learned English as a second language, having grown up exclusively speaking French. When he grew older he attended West Point Military Academy, where he was educated by Robert Anderson, the Union officer who would later surrender to Beauregard at Fort Sumter.

The cadet excelled in artillery drill and engineering, and graduated second in his class in 1938. His classmates delighted in giving him a slew of French pejorative nicknames.

Beauregard spent his time after graduation as an Army engineer, putting his skills to use as he whiled away the days of peacetime. Those days came to an end with the declaration of the Mexican-American War in 1846. His skills as an engineer resulted in his posting with Major General Winfield Scott’s invasion of Mexico.

Dashing, charismatic, and brave, the young Beauregard distinguished himself at the Battles of Contreras and Churubusco. For his actions, Beauregard received a promotion to brevet Captain.

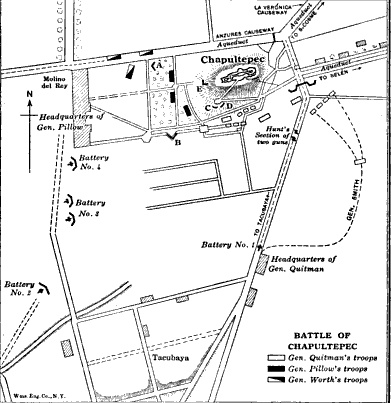

The Battle of Chapultepec would be the hallmark of the young officer’s Mexican-American experience. Before the battle to capture the bastion and secure a vital foothold into Mexico City itself, Major General Scott held a council of war to plan the best course of action against the well-defended fort anchoring the city’s defense.

At the council of war, most of the officers favored taking the Candelaria gate into the city. Beauregard disagreed. He explained that a better tactic would be a feint at Candelaria and an attack at the Chapultepec fortress, followed by an assault on the San Cosme and Belen gates into the city.

Though such an attack posed a risk, as any assault on an anchor point did, the idea of leaving the anchor while assaulting the gate no doubt affected the brevet Captain’s opinion.

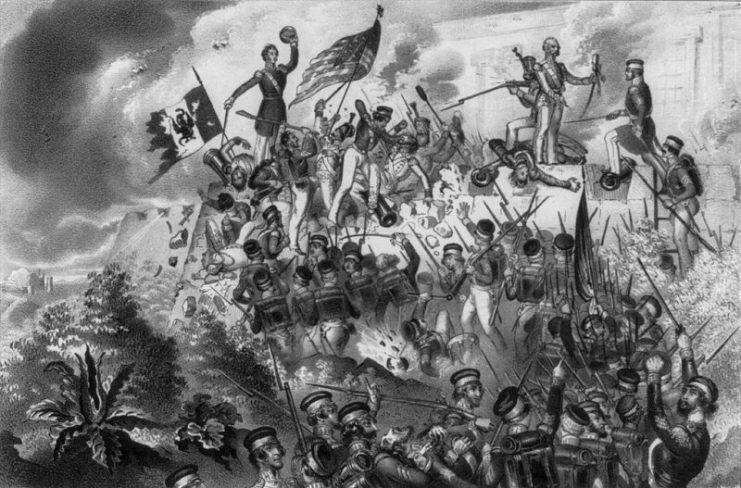

General Scott, carefully weighing the words of Beauregard and another young officer on his staff named Robert E. Lee, decided in favor of an assault on Chapultepec. The Major General then planned out the assault on the fort and the city beyond. Though risky, the attack on Chapultepec proved a success.

During the battle itself, Beauregard worked with the artillery batteries, making sure they remained in optimal shape before and during the battle. For his bravery and tactical expertise, Beauregard received the brevet rank of Major.

Thanks to the Marines and American courage, Chapultepec fell. Mexico City followed, and the war finally came to an end. In the process the nation’s size doubled, stretching from sea to shining sea. The officers, meanwhile, quietly returned to their peacetime lives.

Beauregard would later write about his time in the Mexican war. Rankled by Scott’s praise of Lee, despite what he viewed as his more important involvement, the future Rebel wrote bitterly of his former superior officer and fellow officers during that time.

Despite such grumblings, when the South rose up in arms against the Union in 1861, Beauregard, a southern officer and gentleman to the core, resigned his U.S. Army commission to don Rebel gray. Having served the Union gallantly, and having learned how to sway superior officers to a different tactical course, Beauregard now put those skills to use in the fight against the Union.