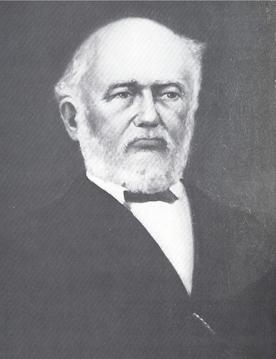

The 16th President of the College of William and Mary, Benjamin Stoddert Ewell was a civil engineer who served in the Confederate Army. His ingenuity with brick and stone was unsurpassed and his talents surely came in handy for the CSA. He served in 1861 and 1862 in the Army of the Peninsula under the express command of General John B. Magruder.

His younger brother, General Richard Ewell, would become far more famous during the Civil War. However, Ben Ewell’s efforts during the Peninsula Campaign especially in building the Williamsburg Line defenses contributed to the Confederate success in the defense of Richmond.

At the start of the American Civil War, Ewell was a captain of the College militia, but as time progressed more students left school to enlist in the CSA and not long after, the school was shut down. Ewell then decided to join the army.

Ewell hailed from James County, Virginia, and was initially opposed to the Confederate secession of the Union but as the war went on he had to pick a side, realizing that his opinion was not going to bring about any change in the already existing feud. Ewell proceeded to establish the 32nd Virginia Infantry as a local defense unit at Hampton. The unit was accepted as part of the CSA in July 1861.

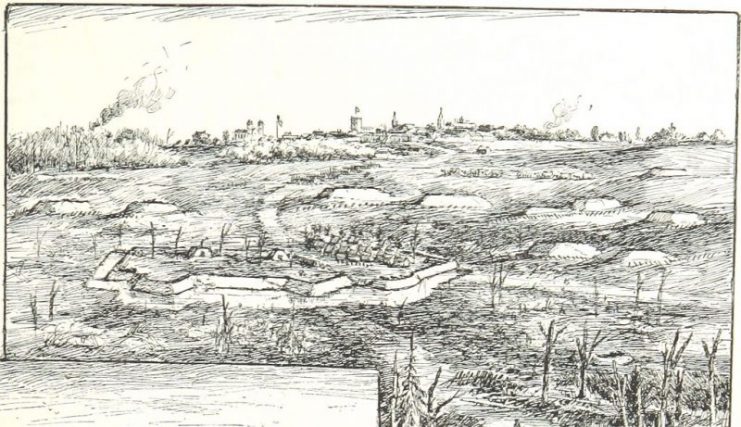

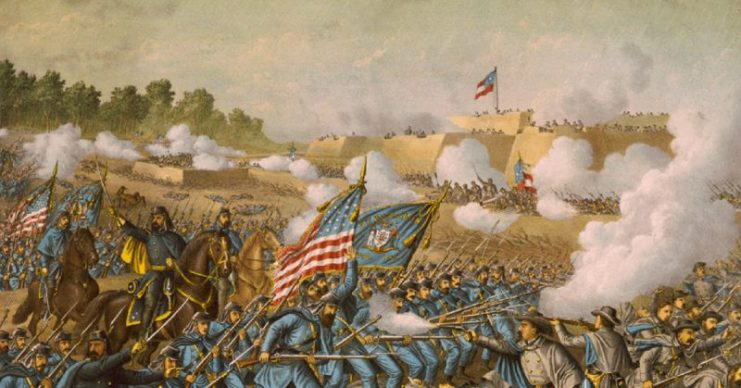

His fame grew within the army when he successfully carried out the construction of the Williamsburg Line under short notice. The line was a series of defensive earthen fortifications stretching across the Virginia Peninsula, east of Williamsburg.

The redoubts numbered a total of fourteen built between Queens and College Creeks with Fort Magruder (6th redoubt) named after the commanding officer. It was strategically positioned at the junction between two main roads – Lee’s Mill Road and the Williamsburg-Yorktown Road.

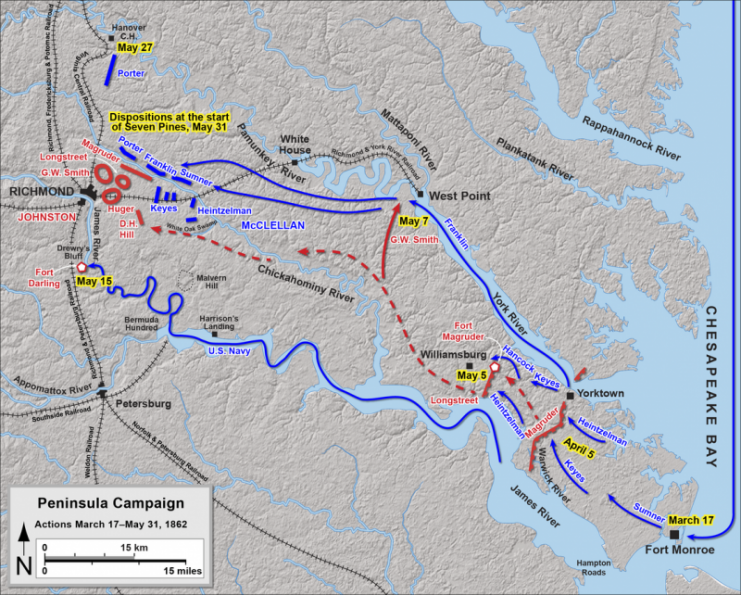

The line was constructed under orders from Magruder in an attempt to slow down Union forces seeking to proceed further south towards the Confederate capital at Richmond as part of the Peninsula Campaign.

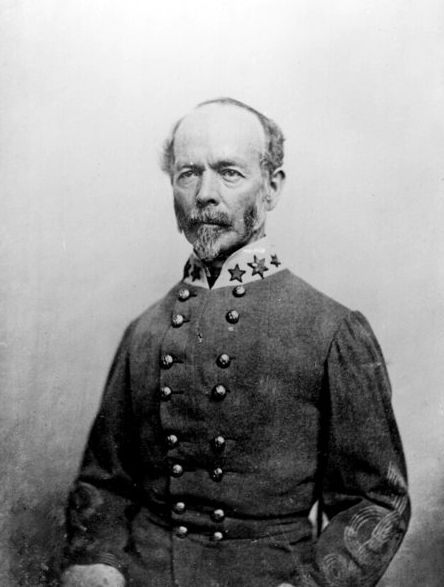

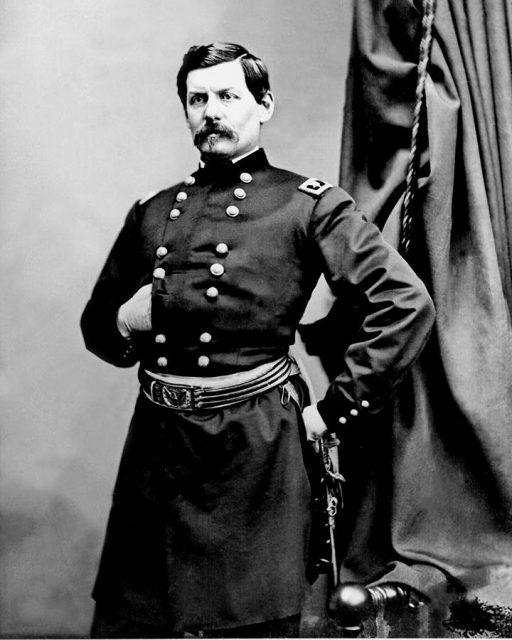

Following the Confederate Army’s retreat from the Warwick-Yorktown Line, General Joseph E. Johnston set up a rear guard along the Ewell-constructed redoubts. Union forces continued in hot pursuit with a 41,000-man force led by Brigadier Generals Joseph Hooker and Phil Kearny. Still unaware of the opposition’s agenda after the affair at Yorktown, the Confederate Army simply retreated after a long display of their strength.

Notwithstanding, the Confederates retreat was slowed down by the bad roads of the lower Peninsula as well as the advance of the Union troops. Both armies were having trouble making their way through the dark muddy tracks of the Peninsula. Moving swiftly under such conditions had not been a part of whatever little training the inexperienced soldiers had been given.

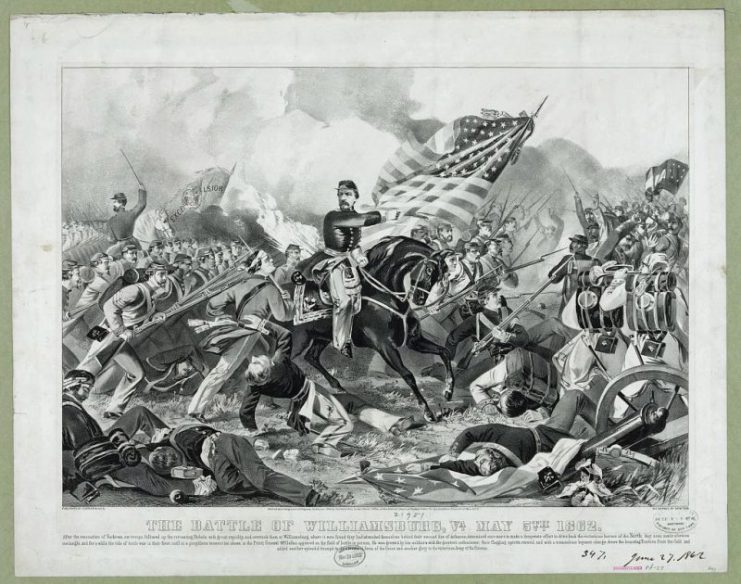

The CSA’s construction of the forts was a strong indication that they would surely engage the Union forces this time, which they did, and in the early hours of 5 July 1862, Hooker’s 2nd division of the Third Army Corps launched an attack actively centered on the 30 ft. tall Fort Magruder.

Hooker then advanced, albeit slowly, to the south, engaging the resistance there and the fighting continued. Both sides sustained significant casualties and ammunition soon began to run out. The two opposing commanders called in reinforcements. Hooker requested that Kearny’s Third Corps march forward to support the Union forces and strengthen their attack while Johnston called on Lieutenant General Ambrose P. Hill.

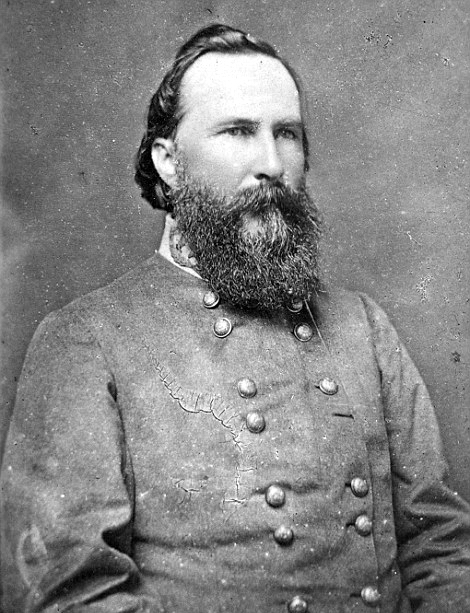

Waiting for reinforcements to arrive took some time and this allowed Confederate General James Longstreet, the commanding officer, ample time to bring up an extra three brigades to support his flanks and thereafter launched his first assault by mid-afternoon in a series of counter-attacks on the crippled Union lines, forcing them back.

Kearny’s division finally arrived just in time to prevent the Union forces from falling into chaos. He arrived into the battle after a spirited cry to his troops: “I am a one-armed Jersey Son-of-a-Gun, follow me!” The elevated hearts of the soldiers helped to restore the Union’s position in the field of battle and fighting continued for most of the day.

A swift maneuver by Brigadier General Winfield Scott Hancock on Longstreet’s flanks eventually caused the relentless Confederate soldiers to abandon their positions on the Williamsburg Line by nightfall and retreat further towards their capital.

Despite the pitched fighting, the status of the battle was inconclusive. Union casualties numbered 2,283 compared to the Confederates’ 1682. The Union Army came into the battle with troops well over that of the Confederates, whose army was comprised of only 32,000 men.

On one hand, the Federals recorded their advance further toward the Confederate capital of Richmond as a “brilliant victory.” On the other hand, the Confederates had successfully stalled the Union Army’s advance to the capital which to them was a huge accomplishment.

However so, the Williamsburg Line’s contribution was very significant to the outcome of the battle. Meeting the Federals in open battle without those forts would have brought about far more devastating results for the CSA. They were outnumbered and also needed to hold positions in order to slow down the Union advance. The Battle of Williamsburg became the first pitched battle of the Peninsula Campaign.

After the battle was over, Ewell left the 32nd Virginia Infantry and was assigned directly to Johnston’s division. He was later sent as an adjutant to his younger brother, General Richard S. Ewell who was a senior commander in the CSA and worked closely with the General-in-Chief, Robert E. Lee.

Ewell’s work at Williamsburg contributed to the Confederate victory at the Battle of Richmond in August 1862 and the end to the Peninsula Campaign.