The Medal of Honor is often the pinnacle of an individuals’ path from modest and unassuming beginnings. In the case of WW2 submarine legend Eugene Fluckey, the prestigious award was but one of many significant events in a proud career of determination and courage.

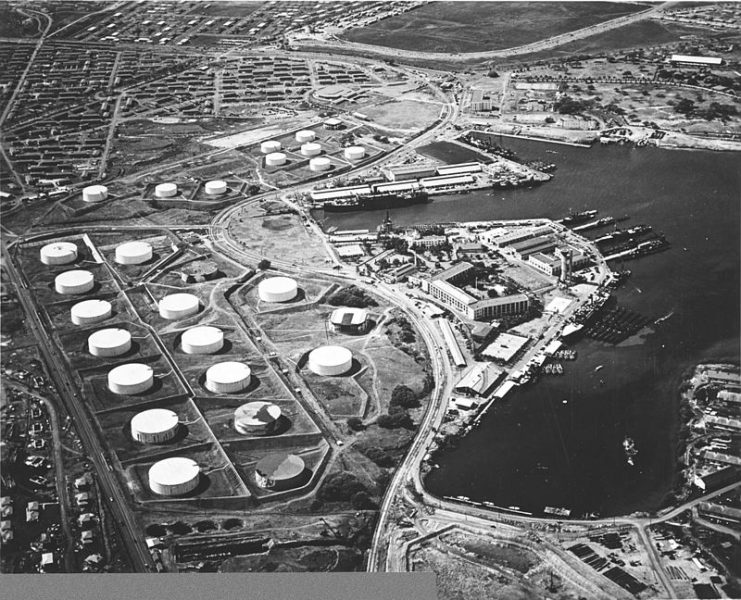

The attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 left the United States Navy at an extreme disadvantage. The total loss of four battleships and the considerable damage to four more stunted the offensive capability of American naval forces at the start of the war.

Untouched, however, were the submarine base and the four submarines moored there. If the United States was to jump back into the fight as quickly as possible it would take men like Eugen Fluckey to lead the way.

The Growing Value of Submariners

American naval doctrine during the interwar years struggled in the shadows of the limitations and economic restrictions following the First World War. Submarines were remembered as the perpetrators of an uncivilized method of warfare with the German campaign of “unrestricted naval warfare” against the merchant ships which formed the logistical lifeline of Britain and France.

Consequently, the application of submarines within the U.S. Navy was, for the most part, relegated to either defensive assets to protect major ports or as screening units in support of larger surface fleets.

The Japanese acts of aggression on American naval assets at the end of December completely upset the contemporary theory of naval warfare held by most American planners and leaders. As one of the first combat assets available for immediate offensive action against the Imperial Japanese Navy, U.S. submarines and commanders like Eugene B. Fluckey became the most important warships in the early days of the Second World War.

A Star in the Making

Born in Washington D.C., Fluckey’s interest in military history and education established a pattern of steadfast determination. Confident and eager to challenge himself, he sought an appointment to the United States Naval Academy at the urgings of his neighbor and recipient of the Medal of Honor for actions at Vera Cruz in 1914, Adolphus Staton.

Despite the lack of available slots, Fluckey’s drive caught the attention of Illinois Representative William Holaday, who assisted and ultimately endorsed Fluckey. Appointed in June 1931, Fluckey began his path toward destiny.

Finishing 99th of 463 midshipmen in the Class of 1934, Fluckey’s time at Annapolis was not without concern. In his third year at the Academy, Fluckey was diagnosed as nearsighted. With the prospect of immediately being forced to resign upon completion, Fluckey focused his attention and efforts into overcoming his poor vision.

With progressive prescriptions and a strict self imposed routine, Fluckey eventually passed numerous eye exams administered by astonished medical personnel.

Following brief assignments to the USS Nevada and USS McCormick, Fluckey chose to pursue continued service with submarines. Assigned to the problematic USS Bonita on 11 June 1941, it was upon completion of a routine patrol in the Caribbean, that the crew learned of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Determined to get his own command, Fluckey pursued graduate school and, after deliberate networking as a solution to personnel problems on the USS Barb, was assigned as a Prospective Commanding Officer on the Barb, setting out on his first war patrol on 2 March 1944.

Into the Fight

Fluckey proved to be an imaginative and effective officer from the start of his first patrol to the Straits of Formosa. He found solutions to daily problems, mechanical, personnel, and tactical, with relative ease and a level of tact which attracted the attention of Admiral Charles Lockwood, the Commander of American submarines assigned to the Pacific Theater of Operations. With only one war patrol completed, Fluckey was given the command of the Barb on 28 April 1944.

As the skipper of the Barb from her 8th to 12th war patrols, Fluckey immediately established himself as a calm and capable leader. With only one sinking credited to the Barb in the seven war patrols prior to Fluckey assuming command, the official tally following the war is commendable. That’s 16 confirmed sinkings that were credited to the Barb, including an escort carrier for the win.

Most noteworthy was how Fluckey waged war. His calculated risks brought the Barb back from a variety of perilous situations. From long range torpedo attacks in water too shallow to completely submerge, to ferocious depth charge attacks, to gun battles with persistent escorts, to innovative rocket attacks on Japanese costal facilities, to the only occasion where American sailors turned saboteurs landed upon Japanese soil and succeeded in destroying railroad tracks shortly before the arrival of a train.

In the Running for #1

As a direct result of his leadership, the Barb was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation and the Navy Unit Commendation; Fluckey was awarded Navy Crosses. One for each four of the Barb’s more successful patrols and not to mention the Medal of Honor for his actions during the 11th patrol.

Following the end of the Second World War, Fluckey served in a variety of vital functions within the Department of the Navy. Always looking towards the future of submarine warfare, his contributions to the service embraced evolving technological improvements, the development of the Submarine Naval Reserve Force, and culminated with being assigned as the Director of Naval Intelligence in 1966.

Devoted to the next generation, Fluckey oversaw an orphanage in Portugal upon retirement from the Navy as a Rear Admiral, following 39 years of proud service. In one of his final messages, delivered at the age of 85, the retired Rear Admiral passed on the hard earned perspectives on duty.

Serve your country well. Put more into life than you expect to get out of it. Drive yourself and lead others. Make others feel good about themselves, they will outperform your expectations, and you will never lack for friends. In USS Barb, our philosophy was, “we don’t have problems just solutions.”

Read another story from us: Silent Service Game Changers – The Advent of Nuclear-Powered Submarines

Was Eugene Fluckey the best submarine commander in all of World War 2? That’s a hard question to answer, but one not worth considering is if his name is not in the conversation.