War History online presents this Guest Piece from Christopher Hoitash

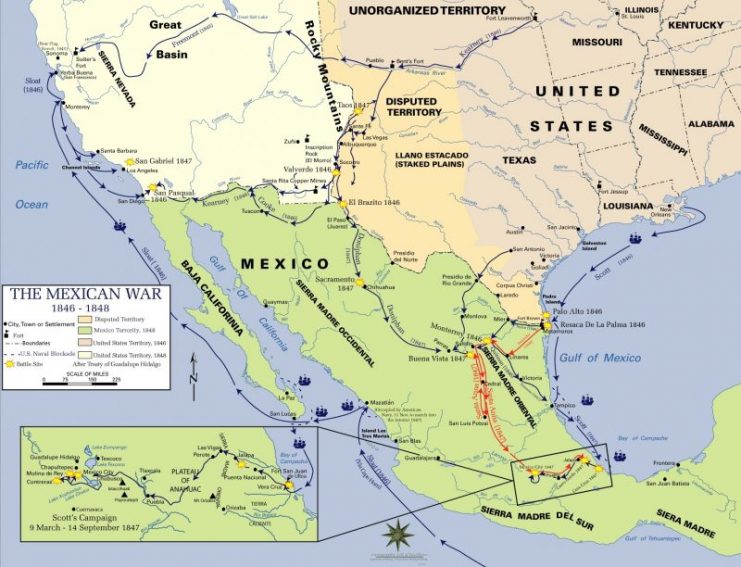

The Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 doubled the size of the United States by halving Mexico. The war, fought over the annexation of the Republic of Texas, started at the disputed border between Mexico and the young republic, a dispute only settled when the United States took the matter to the field of battle in a lopsided war that lingered long in Mexican memory.

In 1836 Texas gained its freedom from Mexico, forming an independent republic. Earned at the end of a sword pointed at Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna, the erstwhile republic and nation of Mexico officially remained at war. Despite this, in the 1840’s Texas made inroads to the United States for annexation. Those inroads met with increased success, and by 1845 the path to annexation was clear.

United States President James K. Polk, an ardent expansionist, prepared for annexation even before his inauguration. Mexico made it plain that annexing their rebellious state would result in war. Polk, confident the United States could browbeat the younger, weaker republic if it came to it, readied the nation for the looming conflict. He also incited the Mexicans, writing both privately and publically that the border of Texas should be the Nueces River, rather than the Rio Grande River as declared by the 1824 Constitution of Mexico. Outraged, Mexico mobilized its forces, ready to defend its national honor and border.

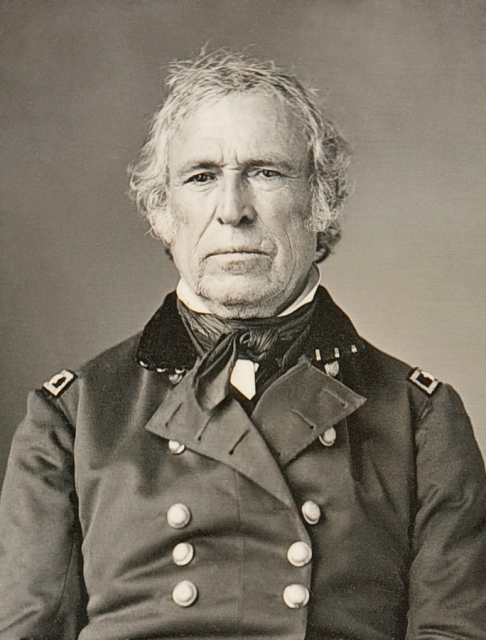

Secretary of War William L. Marcy, meanwhile, ordered General Zachary Taylor to march to the Rio Grande River, south of the Mexican recognized border, and set up a defensive line. Considered Mexican territory to anyone not wanting to annex Texas or go to war over the annexation of Texas, the Mexican response was inevitable, just as President Polk hoped.

When word reached Mexico City of the impending invasion, they quickly dispatched troops to the town of Matamoros, just a stone’s throw from the river. General Taylor’s troops observed the Mexicans in the distance as his forces approached, and, when the Americans reached the Arroyo Colorado stream north of the Rio Grande, the defenders made their stand.

General Pedro de Ampudia, General Taylor’s counterpart, sent a messenger to the American commander on April 12, 1846, decrying the “incredible manner –you will even permit me to say an extravagant one- if the… general rules established and received among all civilized nations are regarded- has not only insulted, but has exasperated the Mexican nation….” Calling the Americans presence south of the Nueces a “conquering flag”, General Ampudia warned General Taylor to withdraw from the Nueces Strip, and that if he did not, it would “clearly result that arms, and arms alone, must decide the question; and in that case I advise you that we accept the war to which, with so much injustice on your part to provoke us…”

Upon receiving the Mexican message, General Taylor replied in kind. Stating that as a solder, international politics lay beyond his purview, he could not help remarking that “the government of the United States has constantly sought a settlement, by negotiation, of the question of the boundary….” Declaring his orders prevented him withdrawing from the Strip, General Taylor went on to say that while he regretted war remained the only alternative, he would carry out his orders, “leaving the responsibility with those who rashly commence hostilities.”

By April 24, General Ampudia had been superseded by General Mariano Arista, and the Mexican forces in the area numbered roughly eight thousand. No longer willing to passively hold the line against the Americans, General Arista ordered a cavalry detachment across the river. Observing the Mexican’s movement, US forces responded with a squadron of dragoons. Outnumbered and outmaneuvered, the dragoons ended up in a firefight that cost almost a dozen lives before the Americans recognized the futility of their position and surrendered. The first true shots and lives of the Mexican-American War were shot and lost.

Once informed of the skirmish, General Taylor wrote to the Adjutant General of the Army regarding the matter. In his dispatch General Taylor reported “a party of dragoons sent out by me on the 24th instant to watch the course of the river above on this bank became engaged with a very large force of the enemy…” and that “Hostilities may now be considered as commenced…”. Readying for war, General Taylor requested four regiments of volunteers from the Texas governor.

Less than a month after the skirmish at the Nueces Strip, President Polk wrote his war message to Congress. In his message, President Polk declared “The Mexican forces at Matamoros assumed a belligerent attitude…” and that “On that day [the 24th of April] General Arista, who had acceded to the command of the Mexican forces, communicated to General Taylor that ‘he considered hostilities commended and should prosecute them.’”

Twisting the words of the Mexicans and General Taylor, President Polk utilized every trick in the diplomatic playbook to sway Congress in support of the war. Though many groups remained unconvinced, including a young Whig politician by the name of Lincoln, Congress acceded to the President’s message and declared war on the United Mexican States. Thanks to the bloodshed at the Nueces Strip, ordered their by General Taylor, the Mexican-American War had begun, and would not end until America spread from sea to shining sea.

Cited Sources:

Ampudia, Pedro de. Dispatch to General Zachary Taylor (April 12, 1846). A Brilliant National Record: General Taylor’s Life, Battles, and Dispatches (Philadelphia: T.C. Clarke, 18470, 43.

Brands, H.W. Lone Star Nation (Doubleday Press, 2004.)

Polk, James K. War Message to Congress (May 11, 1846.) A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 1789-1897 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1897), 4:437-38, 441-42.

Singletary, Otis A. The Mexican War (University of Chicago Press, 1960.)

Taylor, Zachary. Dispatch to Adjutant General of Army (April 26, 1846). Origins of the Mexican War: A Documentary Source Book (Salisbury, N.C.: Documentary Publications, 1982), 2:137.

Taylor, Zachary. Dispatch to General Pedro de Ampudia (April 12, 1846). A Brilliant National Record: General Taylor’s Life, Battles, and Dispatches (Philadelphia: T.C. Clarke, 18470, 43.