Today, many people have a slightly distorted view of the relationship between the British and the vast numbers of American servicemen that were ferried across the Atlantic to take part in World War II in Europe. Mini-series and sweet accounts of GIs and British girls falling in love, getting married, and having children overshadow some of the serious problems that existed during the war.

Pfc Edward Shea (of 27 Wentworth Street, Dorchester, Massachusetts) fills up his jeep in the sunshine at the petrol station in Burton Bradstock, Dorset. According to the original caption, the gas station has been taken over by the army. Pfc Shea is helped by local boys Freddy and Chris Kerley, Barry Kneale and Billy Hubbard: one boy works the petrol pump, one holds back the seat, one holds the hose and another cleans the windscreen.

Think of it. Over the course of about two years, the United Kingdom was “invaded” by millions of Americans. On an island of only about 46 million people, this is a significant percentage. Though the Americans from “across The Pond” may have shared some commonalities with their British “cousins,” there were also many differences.

The most notable difference has been parodied in movies and TV shows since the war – the language. Many get the credit for the saying “England and America are two countries divided by a common language.” The communication problem was surmountable though, and while it may have been momentarily frustrating, was of no real consequence.

Other differences were a little more important. One popular saying went “The Americans are overpaid, oversexed, and over here.”

The pay rate for the average GI was significantly higher than that of the English “Tommy” and bred more than a little jealousy. This was exacerbated by the other part of the saying – Americans, whether it was true or not, had the reputation of being “oversexed.”

Likely, most American GIs were just as experienced or inexperienced as their British counterparts. They were mostly young men, many of them from small towns or rural areas, in a time when morals were much different than they are today.

The young men of the 1940s had a lot in common with young men both before and since then: they bragged, often about “things” that hadn’t happened yet. One of the problems was that the GIs talked about “it” whereas many English did not.

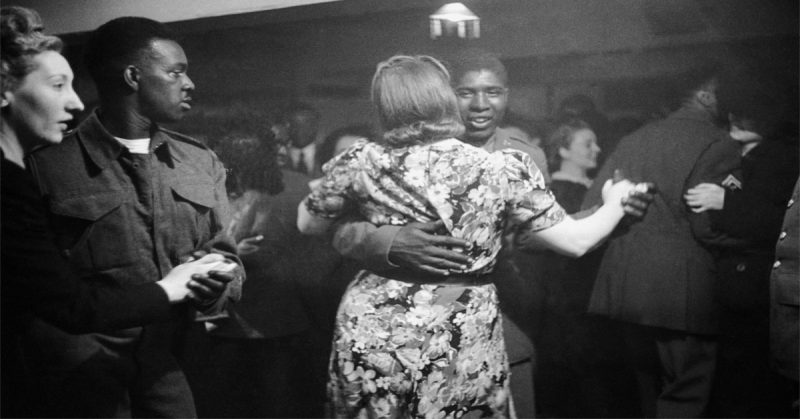

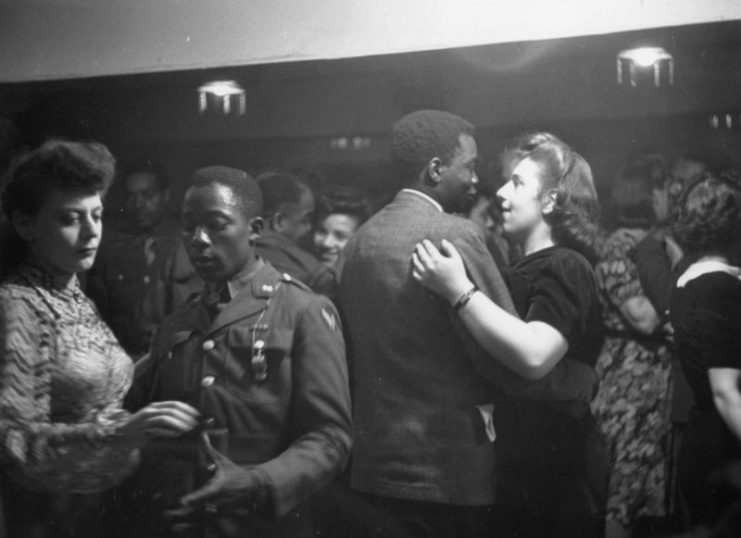

A related problem was that many GIs had pocketfuls of money, and many English women did not. That could have innocent results, such as taking a woman to a dance and spending money on drinks and dinner, perhaps with the hope that things might go further.

But of course, history tells us that servicemen have also used their pay to buy more exotic kinds of “entertainment,” and it could also result in otherwise “upright” women turning to “other” means of making ends meet.

For many in England, oversexed GIs were viewed as a real problem. Both the British and American governments attempted to do something about it, from increased education about each other to increased checks for venereal disease.

But there was another problem that many people, even to this day, do not talk about. Along with the Americans came their attitudes about race. Among the millions of GIs were hundreds of thousands of black soldiers.

Of course, not every white serviceman in the American armed forces was racist, but some of them were. While the U.S. armed forces were on the cutting edge of integration, President Truman’s executive order that ended segregation in the military was not signed until 1948, after the war was over.

Black soldiers and sailors were usually relegated to non-combat roles, such as filling the ranks of support troops or perhaps serving in the artillery, though at wars’ end there were significant numbers of black soldiers in combat in Italy and Western Europe. No matter where or in what unit they served, black soldiers were commanded by white officers and didn’t rise above the non-commissioned ranks.

Segregation was just like at home: separate barracks, mess halls or at least meal times, etc. For black soldiers from the South, this sadly was “normal.” For those from the North, this was a bit of culture shock.

Problems relating to segregation started in England when some white American GIs tried to tell British pub, club and theater owners how to run their businesses. They sought to have their black countrymen banned from entering the establishments that they frequented. Sometimes this went unnoticed, but many times it did not.

England had and continues to have a significant black population. While it definitely cannot be said that race relations in England have been perfect, the same kinds of segregation as in America did not take place there at that time.

British citizens and soldiers could not understand how Americans could be so keen to fight against Hitler’s racist ideals, and yet hold many of the same ideas of white superiority.

Though few knew it at the time, German POWs sent to the U.S. frequently were allowed to go into businesses and use transportation that American blacks were banned from. British women working on American bases could not believe their eyes when they saw segregated facilities.

Even the Red Cross initially refused to take “black blood” in the first war blood drives. Later, they relented after criticism from leading doctors. Even so, the armed forces stored “black” and “white” blood separately. Again, the British working at American facilities were dumbfounded by this.

In 1943, black American servicemen were banned from a bar in Bath in an attempt to appease white American soldiers.

Citizens wrote into the local newspapers by the dozen, one of them saying: “These men have been sent to this country to help in its defence, and whatever their race or creed they should be entitled to the same treatment as our own soldiers.”

One of the worst incidents took place in Lancashire, near the village of Bamber Bridge. There, a group of white American military policemen, one of whom was inebriated, began harassing a group of black soldiers who wanted to go to a local pub.

As the two groups argued in the street, a scuffle began. A group of locals joined the black GIs against the military police, who retreated only to return with two more policemen. Shouting racial epithets, the military police charged into the crowd.

The melee resulted in seven men being seriously wounded in the street fight, which included the use of bricks and bottles as weapons. Thirty-two black servicemen were court-martialed afterward, while the military police were merely reprimanded.

It is recorded that between 1943 and 1944, there was an average of four violent clashes per week between white and black American soldiers. Those were the incidents that were reported.

These stories are included in the book Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, at Home and at War (2015), by Linda Hervieux. The book quotes Willie Howard, who served in the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion and was at Normandy, and who stated that “Our biggest enemy was our own troops.”

Read another story from us: Did Medal of Honor Recipient Break the Rules to Survive?

Other members of the battalion had nothing but positive things to say about the British, who invited them to join their church congregations, took them into their homes, and many times wrote home to the mothers of the GIs.

One letter said: “You have a son to treasure and feel very proud of. We have told him he can look upon our home as his home while in our country. We shall take every care of him… we will look upon him now as our own.”