The Scottish infantrymen, armed with pikes and spears, managed to successfully defend against an English cavalry charge.

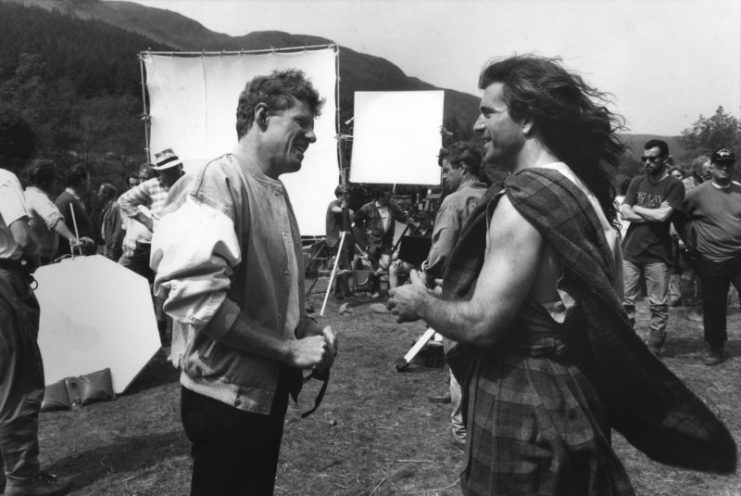

The name William Wallace, once known only by those who had studied Scottish history, became a household name the world over after Mel Gibson’s Oscar-winning movie Braveheart was released in 1996.

As gripping and entertaining as the film was, though, it was not particularly historically accurate. While William Wallace certainly was a diehard Scottish patriot who fought tirelessly and furiously against English rule, Mel Gibson took some pretty extreme liberties with the facts when crafting his movie.

The man we see in the film is more of a fictitious cinematic creation than a representation of the real historical figure whose life is shrouded in a degree of mystery owing to patchy records.

William Wallace was, we can ascertain with reasonable certainty, born in 1270 in Elderslie, Scotland. Unlike the figure portrayed in Braveheart, Wallace was not a commoner but was born into a family of minor aristocracy.

Tradition holds that he was educated by the monks of Paisley Abbey, although simply being literate would not have set him too far apart from a number of his fellow countrymen; in the late 13th century, literacy (although still confined to a minority of the population, especially in the countryside) was becoming more widespread.

As the son of a minor noble, he would also have been taught something of the arts of combat from an early age. He would have learned the basics of swordsmanship as well as horse riding, although is it not known whether he actually trained as a knight.

Because his father was a landowner, Wallace would likely have had experience hunting and shooting with bows as well. It is also thought that he may have served as a mercenary for a time.

Wallace’s early years were likely spent in peace. The reigning monarch of Scotland at the time was Alexander III, a popular and competent leader whose rule was generally a time of peace and stability. However, things changed rather drastically after his death in 1286.

Alexander III died without male heirs, and a power struggle between several different factions ensued. For a time his only descendant – his granddaughter Margaret – sat on the throne, but she died in 1290.

The struggled continued, with John Balliol claiming the throne of Scotland in 1292. King John’s reign was opposed by many, a key opponent being Robert Bruce. It was a time of turmoil, with some Scottish nobles appealing to Edward I (nicknamed Longshanks) for aid.

Edward, an ambitious man, began installing men loyal to him in high positions and bribing prominent Scottish noblemen.

King John, in an act of open rebellion against King Edward, attempted to forge an alliance with the French in 1296. Edward’s response was swift and brutal. He sent an English force to dethrone the king and crush the uprising before it could start.

It was around this time that William Wallace came onto the scene. A young man who may have by now garnered some military experience, Wallace led a successful uprising against the sheriff at the English garrison of Lanark in May 1297.

While Braveheart states that the reason Wallace attacked Lanark and killed the sheriff, William Heselrig, was that the sheriff had killed his wife, this seems an unlikely explanation as it doesn’t appear Wallace was married at the time.

Regardless of his motives for doing so, the uprising was a success. William Wallace’s rebellion quickly began to gather momentum, with many Scots flocking to his banner to fight against the English occupiers.

Wallace joined forces with a Scottish noble sympathetic to his cause, Lord William Douglas. Together, they led a successful raid on Scone, taking the town and forcing the English governor, William de Ormesby, to flee.

Concurrent raids and a similar rebellion against English occupation were being led in the north of Scotland by Andrew Moray; he and Wallace eventually joined forces.

Soon after the two of them had combined their growing armies, they took part in the first major battle of what had become the Scottish War of Independence: the Battle of Stirling Bridge on September 11, 1297.

Wallace and Moray’s army was greatly outnumbered by the English force which consisted of around 3,000 cavalrymen and 8,000 infantrymen and bowmen. The Scots met them at the Stirling Bridge, a narrow stone bridge over the Stirling River.

The English began crossing the bridge in the morning, a process that would take a few hours as it was so narrow. Wallace kept most of his force hidden and held his men back until as much of the English force as he believed he could wipe out had crossed. At this point, the Scots charged swiftly into battle.

The Scottish infantrymen, armed with pikes and spears, managed to successfully defend against an English cavalry charge. Gaining control of the bridge, they surrounded and massacred the segment of the English army which had already crossed.

They began to push more English back across the bridge while, on the other side, the English commanders tried to force more troops across to reinforce the men who were being massacred. As a result, the bridge collapsed under the weight, and many English soldiers drowned.

Wallace and his Scots won a decisive victory. The body of Hugh de Cressingham, one of the English commanders who was killed in the battle, was later flayed by the Scots, and pieces of his skin were taken as souvenirs.

In Braveheart, Wallace is depicted wielding an enormous claymore in the battle – which is not entirely inaccurate, but nor does the sword used in the movie represent the type Wallace would actually have used.

While he was said to have wielded a large two-handed sword (the handle and scabbard of which were, rather macabrely, covered with the dried skin of Hugh de Cressingham), it would have been smaller and of a different design to the sword depicted in the movie.

After the battle of Stirling, both William Wallace and Andrew Moray were proclaimed Guardians of the Kingdom of Scotland. Wallace emerged unscathed from the battle, but Moray died of his wounds in November.

After Moray’s death, Wallace led a series of successful – and often brutal – raids into northern England, attacking towns in Cumberland and Northumberland.

Edward I, though, was not going to give up Scotland without a fight. He was determined to avenge his defeat at Stirling Bridge. He sent a larger force, consisting of around 1,500 cavalrymen and around 25,000 infantrymen and bowmen, to retake Scotland in April 1258.

Wallace was unwilling to engage the English in open battle, knowing that his numerically inferior force would be crushed. He avoided the English army for a few months, and the resulting supplies shortages, unpaid wages, and difficulties of moving a large army across large distances almost caused a mutiny in the English forces.

This was what Wallace had been hoping for, but before the English army withdrew to England, it was reported to Edward I that the Scottish army was camped near Falkirk. Edward moved quickly, realizing he finally had his chance to engage the Scots in open battle.

Wallace and his men had little choice but to fight. The Scottish spearmen and pikemen formed up in a number of schiltrons (tight defensive formations with spears and pikes extending outward) to fend off cavalry charges.

The Scottish archers, however, were put to flight by an English cavalry charge, while the Welsh longbowmen wreaked havoc on the Scottish lines. The Scottish cavalry also retreated, forced from the field by the superior English cavalrymen. It did not take long for the English to achieve victory.

Wallace escaped with his life, but his military reputation was now in tatters after this disastrous defeat. He resigned as Guardian of the Kingdom of Scotland shortly after this but remained dedicated to the cause of Scottish independence.

He continued a guerrilla-like campaign against the English for several years and traveled to France to seek the assistance of King Phillip IV. While he did meet with Phillip, the king declined to aid him against the English.

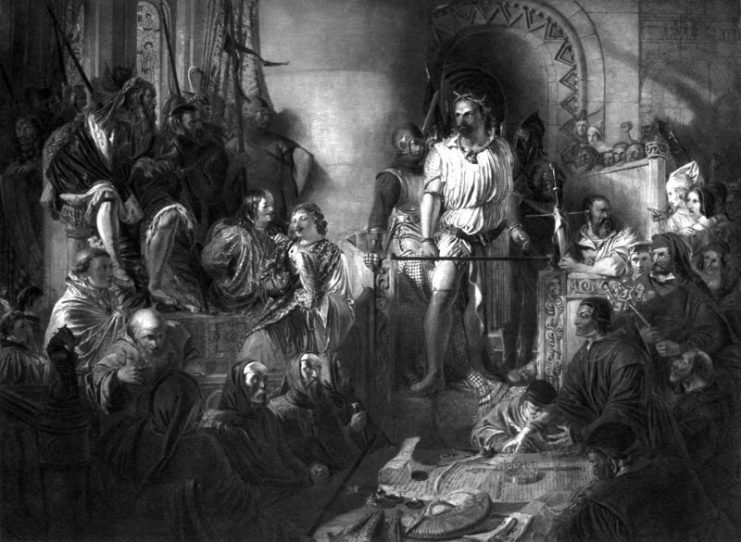

William Wallace was eventually betrayed by a Scottish knight, John de Menteith, who handed him over to English authorities in 1305. Wallace was taken to London, where he was tried for treason – a charge he refuted, saying that he had never been one of Edward I’s subjects. He was also accused of killing civilians in war.

His execution, on 23rd August 1305, was excessively brutal – a detail Braveheart did get right. After being stripped naked, Wallace was dragged behind a horse through the streets of London.

When he reached the site of his execution, he was hanged, but before losing consciousness, the rope was cut so that he could suffer some more. His genitalia were cut off, after which he was eviscerated and his bowels were ripped out.

After all this horrendous brutality, his suffering came to an end when he was beheaded. His head was covered with tar and stuck on a spike above London Bridge as a warning to anyone else considering rebelling against King Edward.

Today, Wallace is remembered as a Scottish patriot and hero. A number of memorials and monuments have been erected to commemorate his life and deeds. The most famous of these is the National Wallace Monument, a tower overlooking Stirling, erected in 1869. And, of course, there is also Braveheart, a stirring if inaccurate account of his life and deeds.