We all know that the Second World War was truly a global war in the sense that battles were fought on many of the world’s continents and oceans.

In another sense, the war was global because many nations declared for one side or the other. Obviously, many more declared for the Allies, for political reasons as well as reasons of kinship and history.

Yet nations in the Western Hemisphere, who had no dog in the fight, declared for the Allies. There are a number of reasons for this. Belief does play a factor, but economics was a much larger one. For example, consider the economic benefits of being allied to the United States.

You may wonder if any of the nations of Latin America that declared war (and that was most of them) ever contributed to the war effort in any way besides providing raw materials. Did Nicaragua provide men? What about Mexico? Peru? Chile? Any of them?

The answer is no, with one exception: Brazil contributed a sizable contingent of soldiers who fought in Italy towards the end of the conflict. One of these “Brasileiros” was Max Wolff. A more German name you could not invent. Indeed, Max Wolff was of Austro-German descent on his father’s side.

His father, involved in the coffee industry, had migrated to Brazil near the turn of the century. His mother’s father was a colonel in the Brazilian Army. Wolff looked like the Aryan-type that Hitler idolized: tall, blond and blue-eyed.

Wolff was a so-called “Teuto-Brasileiro.” Although South America became a place where leading Nazis escaped after the war, the truth is that Latin America, and especially Brazil, was home to many people of German and Austrian descent even before WWII.

As many in the US know, there are more people of Irish descent in the United States than there are in Ireland. Well, the same holds true for people of German descent, and not all emigrants from Germany settled in North America.

Resource-rich and cheap South America called many of them. It is estimated that Brazil had a population of about one million people that claimed German descent before the Second World War.

As in the United States, the German communities in Latin America were divided in their opinion of Hitler and the Nazi regime. Many of these people, or their forebears, had fled German/Prussian militarism in the years of unification in the late 1800s and still more came for the same reason before WWI.

However, a large number came mainly for economic reasons. At that time, Germany (like today) was a densely crowded and relatively small nation where, for many, opportunity was limited.

Their pocketbooks might have been in South America, but their hearts were still in Germany. Many Germans in Latin America and Brazil professed admiration of and loyalty to Hitler. Some of these families sent their sons to fight for Hitler although, for a variety of reasons, the total number is unknown.

Wolff was one of the many Germans who hated Hitler and all that he stood for. When the time came to do something about it, he and just over 25,000 of his countrymen joined the Brazilian Expeditionary Force (in Portuguese, the acronym is “FEB”).

Wolff was one of the few of these men who had some military experience. He had been a military policeman who fought anti-government forces in the Revolution of 1932 and had been seriously wounded. He was one of the few “old men” of the unit, and the younger men looked up to him as a father figure.

When rumor reached Hitler that Brazil was going to send a division of men to fight against him, he scoffed: “The chance of Brazil sending troops to fight is about the same as a cobra smoking a pipe.” The nickname of the Brazilian unit was now official: “The Smoking Cobras.”

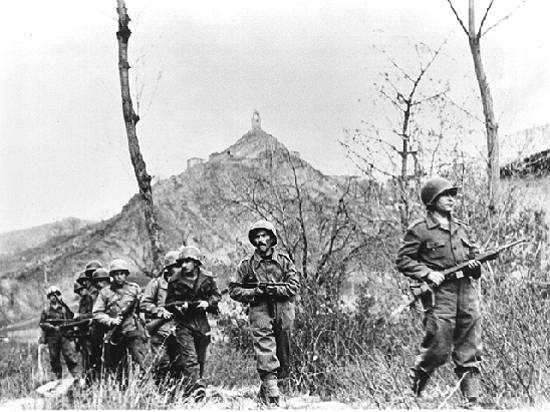

Reaching Italy in the miserable December of 1944, Wolff, a sergeant, was among the thousands of Brasileiros tasked with taking Monte Castello. The mountain is located about 35 miles (about 56 kilometers) southwest of Bologna and was a key fixture of German fortifications in the north of Italy, just before the peninsula widens out in the far north.

Like many new troops, when the Brazilians first arrived they were eager but unprepared. Despite their lack of experience, they were thrown into battle very quickly.

Scaling the hill, they engaged in a fire-fight with experienced German troops and began firing wildly, often at nothing. Of course, this brought a German barrage down on them, the mountain position being the site of a major German artillery position.

One of the men who kept it together was Wolff. He volunteered to run ammunition from the rear to forward units, and he carried the dead and wounded back from the front lines. This type of thing was to become a regular occurrence for him as his men slowly began to learn the ways of combat in the next weeks.

Wolff and his platoon frequently went forward on special missions, ambushing German patrols and doing reconnaissance.

Wolff soon became known as the “King of the Patrollers” for his actions, particularly when his commanding officer called for volunteers to retrieve the body of a dead Brazilian captain. This officer’s body was being used as bait by German snipers, who were shooting at anyone who approached the dead man.

One night, Wolff led a small unit to successfully retrieve the fallen officer.

Since Wolff’s unit fought under American corps command, he was the recipient of the American Silver Star for actions he took in March 1945.

13 Brazilians had wandered into a German minefield during a night operation and set off a chain reaction of mines. 13 men lay dead. Additionally, telephone lines that led from the front to command were cut.

Wolff and three of his men volunteered to retrieve the dead and repair the communication lines. Many believed they wouldn’t come back, but they achieved both mission goals.

The last known picture of Wolff shows him with a hand-picked group of his men. They are all standing leisurely about, all armed with Thompson sub-machine guns. Shortly after the picture was taken, Wolff and his men were sent out to patrol near the town of Montese, 40 miles (64 kilometers) to the southeast of Bologna.

As they crossed an open field with Wolff in the lead, a German machine gun opened up, hitting the Brazilian sergeant and killing him instantly.

Since this occurred weeks into a brutal winter campaign in the mountains, some say that Wolff had a death wish. However, he was remembered by his men as a leader of great bravery who put the lives of his men before his own.