On the 9th of April 1940, Germany invaded Norway. British attempts to protect the country proved futile against Germany’s military might. But for the man assembling Britain’s covert fighting forces, this would provide him with a valuable opportunity to experiment with commando tactics.

The Fight for Norway and the Birth of Commando Operations

Norway sat on crucial routes for the iron trade and ports facing out into the North Sea, resources that the Germans couldn’t afford to let their enemies control.

Britain, which had been considering invading Norway to keep it out of German hands, now leaped to the country’s defense. As German troops marched north and the outnumbered Norwegians set about a determined attempt to hold them up, Britain sent in its own expeditionary force.

Around the same time, a department known as MI(R) was forming units of irregular soldiers. These specialists were meant to carry out guerrilla operations behind German lines on the continent and, if Britain was invaded, to do the same in defense of the homeland.

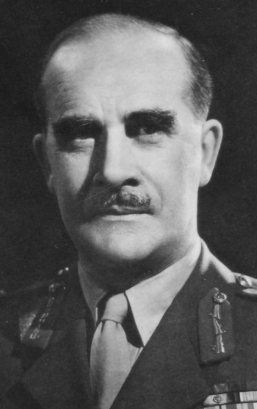

So far, these units were untested. Colin Gubbins, the officer in charge, saw an opportunity to gain experience through the Norwegian campaign.

Creating Scissorforce

Within days, Gubbins assembled four units labeled Independent Companies, which together formed Scissorforce. Their job was to make harassing attacks on the Germans, testing guerrilla techniques in modern warfare.

The companies were quickly assembled from volunteer units waiting to go to France. Each one consisted of 270 men and 20 officers, all equipped with winter uniforms and snowshoes. In theory, they were just what was needed.

In practice, things were different. There was no time for training in how to use the snowshoes, never mind the guerrilla techniques. Most of the soldiers were inexperienced.

20 officers were quickly imported from India, veterans of fighting against guerrillas on the North-West Frontier. The companies were also given specialist sabotage equipment, including mines, pressure switches, and time triggers, to use in destroying railway lines. It was as much as could be done on such short notice.

Arrival in Norway

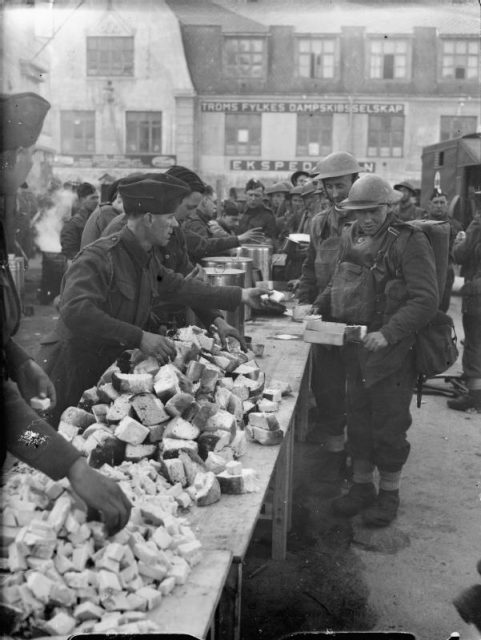

Scissorforce set sail from Scotland on the 5th of May. A few days later, they were dropped off on the Norwegian coast – one group at Bodø, the majority further south at Mosjøen under Gubbins’s command.

The situation they found was a dire one. The Germans were only 20 miles from Mosjøen and advancing fast. Norwegian forces were collapsing. French ski troops, who they had been told would fight alongside them, had instead been ordered to retreat, as the French sought to minimize their losses. Even the captain of the ship that had brought Scissorforce was in a hurry to get out before German bombers caught him.

Gubbins saw that firm leadership was needed if he was to test the theory of war he had spent months studying. As his troops prepared to face the advancing enemy, he moved rapidly across the icy landscape. Driving, cycling, walking, even swimming, he hurried from one place to the next, surveying the situation and delivering orders.

Having linked up with Norwegian partisans, he heard their reports on the strategic situation. A German army was advancing fast toward Mosjøen, up the main road from the south. Ahead of them was a large scouting force of cyclists.

This was a chance to take on the Germans. Gubbins was determined to make the most of it.

The Mosjøen Road

Gubbins placed a force on the road under Captain Prendergast, one of the men he had imported from the Indian Army.

Prendergast had seen the ambush tactics used by Pathan guerrillas, and now he planned to use them to his advantage. He spent the night reconnoitering the ground around the road, then set his men up in ambush spots. Their goal was to hit hard, hit fast, and then get out.

The thick, soft snow made movement hard for Prendergast and his men, but they had time to take up their positions. He chose an ambush spot where the road narrowed to cross a river, not far from Mosjøen. A lake and a ridge flanked the road, making escape difficult. Blocks at the ends of the bridge would force the cyclists to dismount, leaving them slow and vulnerable.

An hour after digging in, the ambushers saw the Germans approach. Prendergast waited until the targets were at their most vulnerable, when the lead men were halfway across the bridge, then he gave the signal to open fire.

Within seconds, Germans were dropping like flies. Those near the rear dived into a ditch, but Prendergast, predicting this, had already stationed men to fire into it.

The Germans only managed to fire two rounds between them. All 60 were killed.

Retreat

Gubbins hoped to repeat the attack, but there was no opportunity. In the face of the inexorable German advance, he was forced to retreat. Along the way, his men continued using the tactics he had planned for, blowing up anything they could to stop the Germans.

But the men weren’t trained for the hardship of guerrilla warfare in a Norwegian winter, and there was only so much they could do.

At Bodø, the British prepared defensive positions and waited for evacuation. The Germans had mastery of the skies and sent their bombers to punish the men who had ambushed their cyclists. By the time trawlers carried Scissorforce out, Bodø was in ruins.

Read another story from us: The Nazi Invasion of Norway – Hitler Tests the West

Lessons Learned

The Scissorforce expedition was a valuable learning experience for Gubbins. It became clear that extensive training and preparation were needed before sending men into this sort of fighting. When MI(R) was merged into the new Special Operations Executive (SOE) a few weeks later, Gubbins was put in charge. He took the opportunity to create an extensive program of training and special weapons development.

Next time, his commandos would do more than kill a few cyclists.