From sabotaging factories to ambushing patrols, guerrilla warfare played a vital part in the Second World War. From early on, the British sent covert operatives to carry out these missions, as well as supporting locals in areas occupied by the Germans.

These missions created a challenge for the men in charge, as there were no existing programs or textbooks to train men in this way of fighting. Someone had to write the book on guerrilla warfare.

Creating a New Sort of Manual

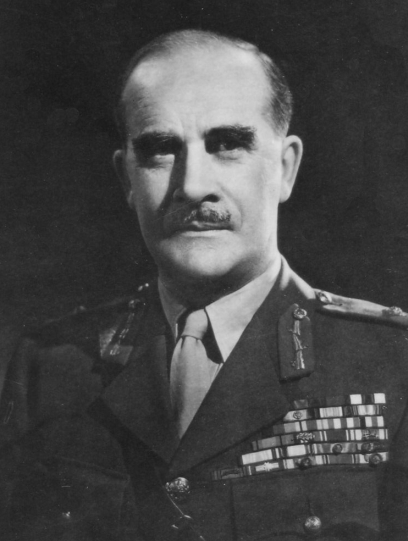

The man who did this was Colin Gubbins. Smartly dressed and with the civilized air of a British officer, Gubbins was an unlikely inspiration for guerilla warfare.

But beneath his sharp exterior lay a man with experience of the darker side of combat. A veteran of the First World War, he had subsequently fought against the Bolsheviks in Russia and Republicans in Ireland, spent a tour of duty in India, and finally found himself in military intelligence.

Seconded to the newly formed Special Operations Executive (SOE), Gubbins became responsible for all aspects of the covert war, including training and equipping combatants.

One of his first priorities was finding a training manual, but he quickly discovered that no such thing existed. No matter how many libraries he scoured, he found no such book in any language.

Therefore, he set about creating his own, a project which would eventually create two books: The Art of Guerrilla Warfare and The Partisan Leaders’ Handbook.

Searching for Inspiration

Gubbins wanted clear, usable guides that would educate his men in how to do the maximum amount of damage to their enemies. For this, he turned to a variety of sources.

T. E. Lawrence, popularly remembered as Lawrence of Arabia, was a natural starting point. A British officer with a gift for speaking Arabic, Lawrence was stationed in Cairo as an intelligence officer in World War One.

Having been given the task of liaising with Arabs rebelling against the Turks, he soon went beyond mere coordination, leading hundreds of rebels in raids against Turkish troops and railway lines.

His adventures, which he himself recorded in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, were the most famous precedent for irregular warfare by any British officer. They provided excellent examples of how to work with locals and make life difficult for the enemy.

Gubbins was just as willing to draw inspiration from enemies as from allies. He had fought against Republicans in the Anglo-Irish War, seeing firsthand how successful an irregular army could be.

A few thousand armed men, organized in secret and supported by civilians, had caused chaos for the British using ambush, sabotage, and assassination.

The Republican campaign had led to the liberation of Ireland. If their tactics could be successfully imitated, perhaps the Allies could liberate Europe from the Nazis.

A more surprising inspiration was Al Capone and his mob of Chicago gangsters. Operating during the prohibition era, Capone had become a seeping wound in the side of the city.

Hit-and-run attacks by his men proved devastatingly effective, making him the most feared and famous criminal in America.

Gubbins was inspired by Capone’s success in striking his enemies by surprise, causing maximum carnage and terror. Capone’s choice of weapons also influenced the SOE handbooks, thanks to the effectiveness of tommy guns in such actions.

Ways of Killing

Drawing on these varied sources, Gubbins developed his own philosophy of unconventional warfare.

The aim should always be for the guerrillas to hit hard, hit fast, and get out afterward, leaving the greatest possible damage in their wake. This was one of the points made in his instruction manuals.

Other points were more detailed and specific.

The manuals covered how to kill men up close. Instructions were included for strangling a sentry with piano wire, taking him out without drawing any attention.

There were instructions for carrying out sabotage attacks, including those using explosives. Gubbins advised on how best to do this to destroy trains and factories, the most common targets for SOE operations.

Operatives were advised first to derail a train, then shoot the survivors as they emerged. Always, the emphasis was on maximum destruction, a focus which would later lead to the development of spectacular specialist explosive devices.

This emphasis on destruction and fear led to some instructions that Gubbins’s superiors would surely not have approved of.

He discussed using deadly bacilli to poison water supplies, using only a pint or two of contaminant to wipe out an entire town.

These tactics didn’t just focus on hitting military targets. There was also plenty about attacking infrastructure, as Lawrence had done when destroying Turkish railways. If the guerillas could undermine the Germans’ ability to fight, then they could make the war more winnable for Britain’s conventional forces.

Small Enough to Swallow

Responsibility for publishing Gubbins’s books fell upon Joan Bright, a secretary recruited by the department just before the outbreak of war. She typed them up and then considered how best to approach publication.

It was Joan who decided that the books should be published pocket-sized, on edible paper. This way, they could be carried by operatives in the field, for ease of reference.

If they were in danger of being captured then an agent could swallow the book, a few pages at a time, in less than two minutes. They just needed a glass of water to wash it down.

Gubbins’s books were strange texts for a strange time. They played an important role in preparing Allied agents for operations across Europe.

The techniques of Chicago gangsters and Irish revolutionaries would help to shape the greatest war the world had ever seen.