It was said that the agents even gave the project the motto of “Every man his own stylo.”

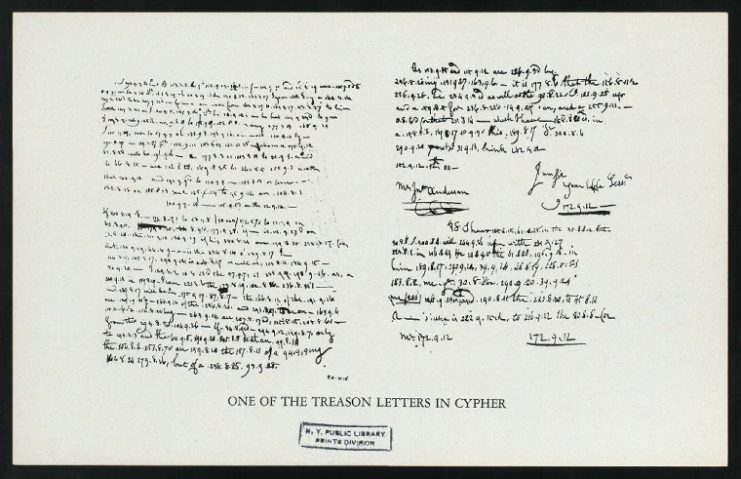

The art of spying includes trying to communicate what intelligence you have gathered in a timely and concealed fashion.

One of the popular ways to do this has been to use “invisible” ink. A message is written using ink that cannot be seen by the naked eye until a chemical or compound was applied to it. The hidden message would then be revealed.

The challenge to overcome was to choose an ink whose ingredients are readily available to a field agent and which are of a very practical nature. Also, what the message needed to be written on should not arouse any suspicion if found on a spy.

Invisible ink was first used in ancient times by both the Greeks and Romans. It had been perfected in Europe by the 16th Century, where various recipes were commonly used like a very popular one based on vinegar and alum.

This was a simple recipe where you mixed a solution of eight parts white vinegar to one part alum powder. Traditionally, the mixture was used to write a secret message on the shell of an egg. Then when the egg was boiled in water until hard inside, the writing would appear on the egg white when the shell was removed.

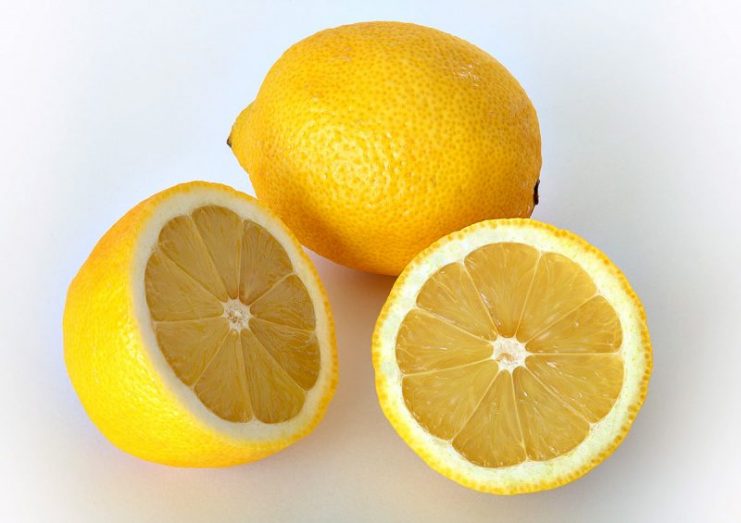

During World War One, lemon juice proved a straightforward and highly effective invisible ink and was commonly used by the Allies. A message could only be exposed clearly with an iodine solution. The paper would turn light blue and the message would show up in contrasting white.

This system, though cheap, had its drawbacks. The message could only be written on paper, and the recipient needed iodine solution to activate the message. Furthermore, the enemy quickly learned to look out for lemon-scented letters!

Another popular invisible ink combination of that era was to write the message in vinegar and use a solution of red cabbage to cause a chemical reaction to reveal the message. But like lemon, odor was a dead give away. Furthermore, on the battlefield, lemons and vinegar might not be readily available.

So in a quest to keep one step ahead of the enemy, one of the most bizarre proposals in spying was allegedly put forward by the Allies.

In 1915, British intelligence MI6 (SIS- The Secret Intelligence Service) was looking at ways of passing secret messages that could not be revealed by the use of iodine since the Germans now knew this was the way to detect Allied secret messages.

MI6 was considered using semen as a source of invisible ink, but abandoned the idea allegedly due to the foul smell and, presumably, because female spies might be at a disadvantage in sourcing a supply.

It was said that the agents even gave the project the motto of “Every man his own stylo.”

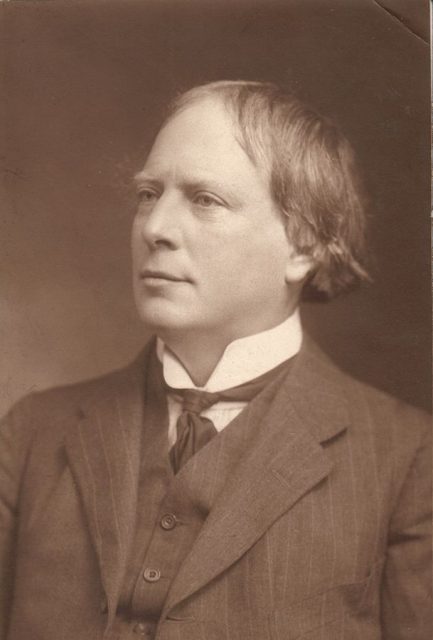

The suggestion is thought to have come from Mansfield Cumming after he had made inquiries at the London University about what might make the best invisible inks.

This may all seem a little far fetched, especially with the man involved being conveniently called “Cumming.” The only brief reference to the proposal was supposedly found in an intelligence officer’s diary some years later. At first glance, it looks very much like being an urban myth.

But, there might possibly be some truth to the story. The Head of MI6 at the time was a Mansfield Smith-Cumming. So it’s not inconceivable that he might have been involved and the “Smith” part of his name got dropped for comic effect when the story was retold.

In addition, it was a well-known fact that he liked finding innovative inventions to aid his agents and that he had a particular fascination for invisible inks.

War does bring about strange misconceptions and tales that seem too bizarre to be true, but nevertheless turn out to be so. Take for example the naming of the “Joystick.” There are many stories behind the origins of this name.

One of the stories goes that a journalist from the Evening Standard newspaper was visiting a British Fighter squadron. When being shown around the cockpit of one of the aircraft, he was told it was steered by a “Joystick.” This was, in fact, the risqué nickname given to it by amorous young pilots as it was positioned between their legs.

Not realizing they were sharing a joke with him, the journalist faithfully reported in his article the next day that the “Joystick” was being used by our gallant pilots to steer their new high-tech fighters into battle.

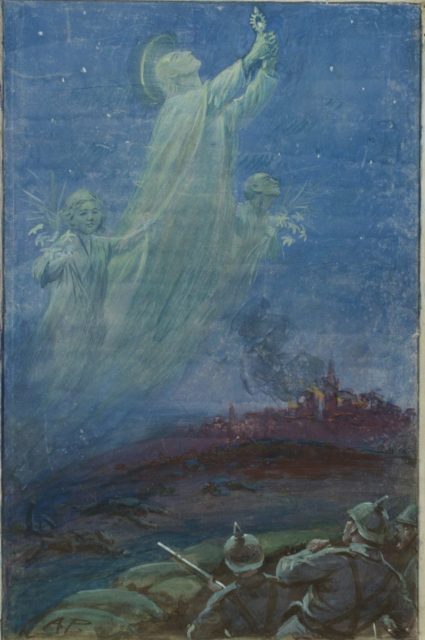

And what about where a large number of British soldiers who claimed to have seen giant angels during the Battle of Mons in 1914? This was later found to be a myth that started with a fictitious short story that was published shortly after the battle.

Arthur Machen had written a story called The Bowmen about a group of ghost archers led by Saint George, who came to the rescue of some beleaguered British troops. It had been featured in the London newspaper the Evening News using the battle as inspiration.

Machen never had any intention for the story to be taken as fact, but the newspaper forgot to mark it as being fiction. Since it was written like a journalist’s account, many found it very believable.

The myth grew so strong that, over a hundred years later, many believe the Ghostly Angels of Mons to be a true event.

Given the above, the story of MI6 considering using semen as invisible ink might not be as far fetched as it sounds.

Sadly there is no record of what reactive compound was needed to reveal any message written with semen. But, as it’s made up of mostly of protein, citric acid, fructose sugar, sodium, and chloride, heat might be a possibility.

Or it might be that the citric acid in semen was deemed sufficient to enable it to be detected by iodine. However, this would be another reason why it was not pursued as an alternative invisible ink for MI6 during World War One.

Read another story from us: Tiger Tanks & Tea: The British Cup of Char in War

Twenty-five years later, during World War Two, the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) came up with a list of what the perfect characteristics of invisible ink should be:

- Mixes well with water.

- It should be a simple and straight forward method.

- Does not produce a tell-tale odor.

- Not easy to detect with the naked eye.

- Does not react with iodine or with any other commonly used detection fluids or compounds.

- Invisible under ultraviolet light.

- Does not discolor the paper it is written on.

- Should not reveal itself under heat.

- Easy to obtain and has at least one plausible innocent use by the holder.

- Not to be an unstable substance.

So, one cannot help but wonder how semen would rate as an invisible ink based on these criteria and compared to the more commonly used lemon solution method.