The United States has always demonstrated its fierce independence by going in directions that other nations might find unusual or even downright odd.

But if it has sometimes proven unpredictable or even curious in its national policies or direction, it has also shown itself a leader in many aspects of the military. Its Navy, in particular, must be granted credit for its advanced and unique approach to ship design and building.

During the 1930s, this propensity for uniqueness proved itself valuable to the U.S. Navy, which was certain it could win any war with the Japanese on the Pacific. (Little did they, or anyone else, know how soon Pearl Harbour would prove them right.) Being a significant threat at sea was what would help the U.S. win, so the thinking went.

That was when the Iowa Class battleship was born.

https://youtu.be/KFhMZwrTiWw

The ship was designed with all the best nautical features modern Navy techniques could offer, but it had something else that no other American boat had: speed.

Up until then, Navy ships could generally command no more than 21 knots, or, if pressed, 27. Such was the case with the Carolina Class of ships, whose designers and engineers had been more concerned with armor and ammunition.

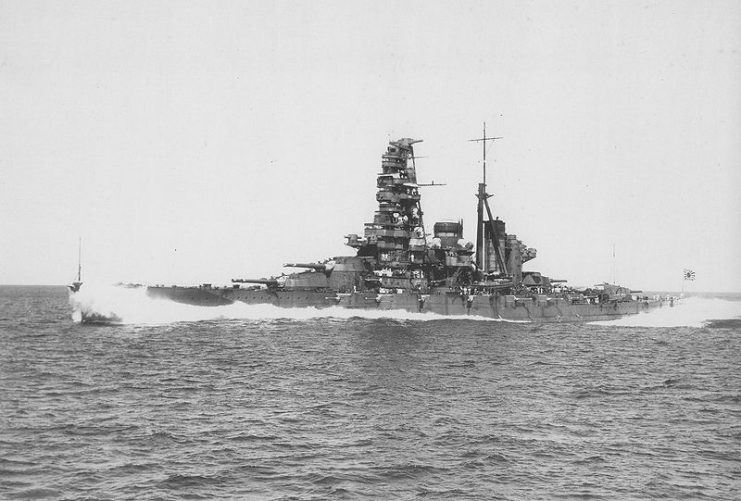

When the Iowa Class was introduced, most people wondered what the fuss was about. It might be able to reach 33 knots but it weighed an extra 10,000 tons, considerably more than the Dakota Class, for example. The reason speed was so important to the Navy was simple, really: the Kongo Class battleships in Japan’s Navy.

America knew that it would have to make a strong advance through the sea to go up against Japan’s Kongo Class battleships, which were equipped with eight, lethal 14” guns, and could reach 30 knots. Navy experts believed that these boats could penetrate U.S. cruisers, thereby making it “open season” on U.S. supply ships. Therefore, America wanted ships that were faster, and the Iowa Class was it.

Initially, the Navy looked at two separate designs for Iowa. The first one was still focused on armor and ammunition. But the second design was very much like the South Dakota Class of battleships in some of its elements, but it had only a 5,000 yard (over 4,570 meters), so-called “immunity zone” as protection from its shells. American naval designers were often forced to choose between firepower or speed. Historically, they’d favoured the former, but with the Iowa, the Navy chose the latter.

Many people, both inside the Navy and in other branches of government, viewed the Iowa Class with a healthy dose of skepticism. It was believed to have many drawbacks, such as the armor, firepower, and displacement, and not enough mitigating benefits to balance those out. In fact, its level of armor was seen as wholly inadequate in comparison to any other ship in service in the U.S. Navy at the time.

Despite such skepticism, the Iowa ships, like so many new ideas, simply needed time to prove its worth. And it did. Iowa Class ships are the only battleships that remained in “fighting shape” right through the Second World War and up until the Gulf War. The battleships certainly earned the right to be nicknamed the “grand dame” of U.S. Navy battleships, and they proved their worth repeatedly for five decades.