On October 1, 1807, a lone British packet was sailing 110 miles off the Northeast Coast of Barbados. The crew of 28, both men and boys, were nearing the end of their journey. They were sailing for Barbados and the Leeward Islands with a hold full of mail and dispatches.

Packet Ships like the Windsor Castle were vital for the Royal Navy. They transferred personnel, news, and orders around the world as quickly as the wind and weather would allow. To do so, they had to be fast, lightly armed, and maneuverable; but that also made them a target for privateers.

Early that morning the crew were finishing their breakfast and beginning their daily tasks of sweeping the decks, repairing sails and spars, and maintaining their ship. Suddenly they heard the most dreaded call of any packet sailor: “Sail Ahoy!”

The acting Captain, William Rogers, looked to the horizon and saw the faint outline of two masts and sails approaching from behind. It could mean one of three things: a friend, a neutral, or an enemy. The unidentified ship was racing towards them sails billowing as it gained speed.

Captain Rogers ordered lead shot be put in the mail bags. If there was a risk of capture, the mail, and all official correspondence, must be destroyed to keep it from an enemy. For almost four hours the two ships sailed as fast as they could hoping to gain any possible speed advantage. Despite their efforts, the ship was closing in on them and Rogers knew they would have a fight on their hands.

The ship bearing down on them was a schooner, with two masts and sails running fore and aft. She was clearly very fast, maneuverable, and did not appear friendly. Rogers ordered his crew to prepare for action and to repel boarders.

Shortly after noon, in a burst of color and canvas, the French Tricolor flag was raised on the schooner. It was their worst fears. A French privateer; their only hope was to fight.

The French ship opened fire, and cannon balls thundered towards the British packet. Rogers responded with two chase guns on the Windsor Castle. Neither ship hit their mark, but the French knew the packet ship was not surrendering.

Rogers knew his ship was more valuable intact than at the bottom of the ocean. A privateer’s goal was to capture an enemy vessel and sell it. They preferred to scare a foe into submission or board and take it by force. While the battle picked up, Rogers considered his options.

As the French ship fired, she continued to close the gap, until she pulled alongside the British packet. Grappling irons flew through the air and hooked onto the Windsor Castle’s rigging and rails. The French pulled the two ships closer and prepared to jump across the ever shortening gap.

Ten Frenchmen, armed with cutlasses, pistols, and boarding axes made the leap, but Rogers’ crew was ready and waiting. Their long pikes found their mark and impaled the French assailants. While British morale rose slightly, they could see they were outnumbered almost 3 to 1. The French, though, decided to change tactics, and cut away the grappling lines.

The ships remained locked together as high aloft the Windsor Castle’s rigging was tangled in the privateers. The ships crews continued to fire shots at one another. Small boarding attempts were made but were repelled by the British. The Packet’s mail was hung over the side, ready to be cut away and dropped to the bottom of the ocean at a moment’s notice.

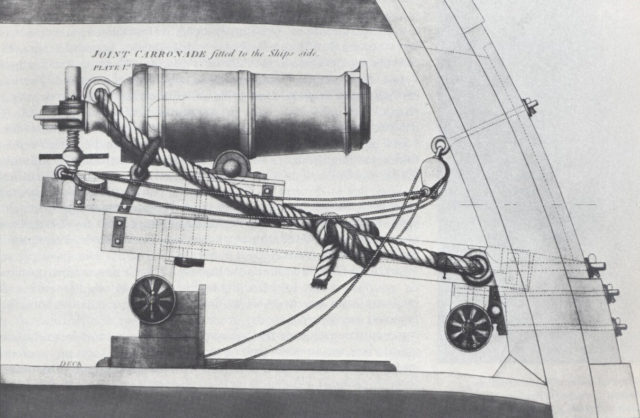

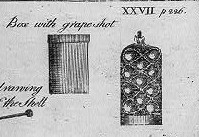

Around 1500, the tide began to turn. The British crew rolled one of their 9 pounder carronades into position, loaded with double grapeshot, canister shot, and around 100 musket balls. They waited for the right opportunity to fire, and it came as the French crews gathered on the deck to make another boarding attempt.

The British prepared their long pikes again and stood fast, but as the French pressed close to the rail ready to jump, the carronade fired. A rain of iron and lead sprayed across the French deck. Men were annihilated where they stood, while nets, sails, and rigging were torn to shreds.

Following the devastating shot, Captain Rogers and five of his crew leaped aboard the French ship. They faced about 60 French, but the privateer’s crew were stunned and reeling from the powerful cannon shot, many were wounded, others dazed.

Fear struck the French, and they scrambled below decks to escape the crazed English sailors and their carronade. The boarders were alone on the deck but knew they could not fight the whole crew at once. Rogers ordered the captives on deck one at a time, clapping each in irons as they came. Finally, the affair was over.

As the smoke cleared, it became apparent how incredibly fortunate the Windsor Castle had been. Her crew of 28 incurred three dead, and ten wounded. Her opponent, identified as the French privateer Jeune Richard, suffered twenty-one dead and thirty-three wounded out of a crew of 92.

The British packet had captured a well armed and fast privateer schooner, making life in the Caribbean just that much safer for English merchants.

Small single ship actions were often the most vicious. Large fleets battled in strict formations and from a distance, but two ships grappling pitted men against one another.

In few cases have men shown such bravery, skill, or ingenuity as the crew of the Windsor Castle on that day, October 1, 1807.