People used to think of spying as dishonorable. Many British officials rejected it in WWII – they wanted to fight a “gentlemanly war.” Churchill felt otherwise, however, which turned the war in Britain’s favor. The Cold War and James Bond films further changed the public’s perception of spying into a glamorous, even sexy adventure.

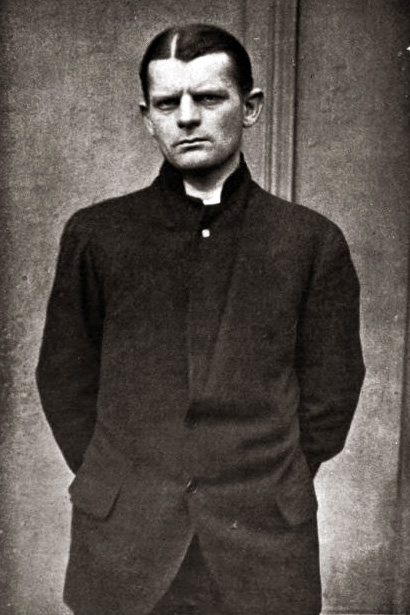

However, in WWI few countries had a specialized secret intelligence service. Carl Hans Lody was a far cry from the suave James Bond and not because he was German.

Born on January 20, 1877, in Berlin, he was orphaned when he was young. At age 16 he joined the Imperial German Navy and worked his way up the ranks to become a captain.

A serious illness put an end to his naval career, forcing him to become a tour guide with the Hamburg America Line – a German luxury cruise company that sailed between Europe and the US. While working there, the 35-year-old Lody met a wealthy young German-American woman whom he married in October 1912.

They settled in Omaha, Nebraska but the marriage did not last long, and they divorced in February 1914. Lody returned to Berlin where he was approached by the Nachrichten-Abteilung (German naval intelligence) who recruited spies.

Given his naval experience, familiarity with international ports, fluency in English, and time spent in the US, Lody was an ideal candidate. He willingly signed up. In May he was in France reporting on what was happening. Then he was transferred to Britain.

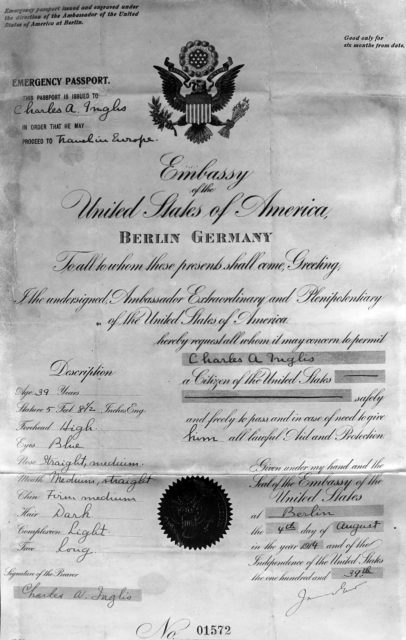

He was sent to the Firth of Forth in Scotland’s Edinburgh-Leith area because of the warships docked there. At the time the German government believed it could win the war with a single decisive naval battle. With a false passport in the name of Charles A. Inglis, he arrived in Edinburgh in August.

He had no training or code-books, only a set of addresses in neutral countries he was to send his reports to. Spy-fever had gripped Britain, and some German agents had been arrested; Lody needed to be careful.

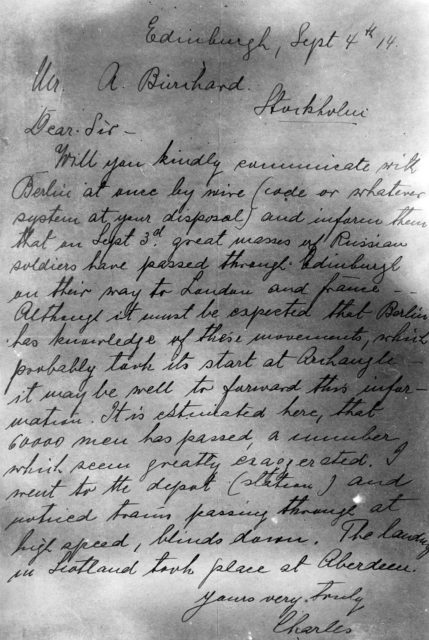

However, his very first telegram to Stockholm was intercepted as British intelligence knew the address was a cover for German agents. As it was not in code (none of his reports were) and contained no sensitive data, they allowed it to be sent. Unaware, but hoping to cover his tracks, Lody moved out of his hotel and into a boarding house.

British intelligence, meanwhile, began wondering if they might have an ally in the German. On September 4, he reported that 60,000 Russian troops had passed through Scotland on their way to France. No such thing happened. It was merely a rumor he had heard, but it made the Germans nervous.

He then traveled to London and reported on the city’s security measures on September 15. He was back in Edinburgh two days later and was told by sailors about British plans to mine German waters. Incredibly, although true, he did not believe it and did not report the incident.

On September 27 he sent a report containing detailed information on Scottish coastal defenses; it was intercepted and not sent on. By then Lody’s landlord was becoming suspicious about him. Fear of espionage was very great and every day foreigners were under suspicion.

Concerned, the Germans sent an agent to provide him with a safe address, but Lody had fled to Ireland. Traveling through Liverpool, he gained more military information which he sent on September 30, but the British were no longer passing his reports on. The manhunt for Lody had begun. They found him on October 2 at the Great Southern Hotel in Killarney.

Taken to London, he was kept at Wellington Barracks – but there was a problem. He had been spying on Britain, but he had done it “outside the zone of operations” of the war. Under British law, that did not qualify him as a spy.

The Manual of Military Law had been published earlier that year in February. Unfortunately, it was also vague about what defined a spy and how, exactly, to punish one. It was also unclear as to whether a person should be court-martialed or tried by a military tribunal. On October 21, it was decided Lody would be tried by the High Court – the trial took place nine days later.

On November 2, Lody was found guilty of two counts of war treason based on two letters he had sent from Edinburgh and one from Dublin. He freely admitted to what he had done, impressing everyone with his calm and dignified manner.

He was sentenced to death on November 5. Lody then wrote his final letter – thanking his guards for their “utmost courtesy and consideration.”

The Tower of London, originally a castle, had been used as a treasury, public records office, and a prison. It was also where traitors were traditionally executed.

On November 2, Lody was found guilty of two counts of war treason based on two letters he had sent from Edinburgh and one from Dublin. He freely admitted to what he had done, impressing everyone with his calm and dignified manner.

He was sentenced to death on November 5. Lody then wrote his final letter – thanking his guards for their “utmost courtesy and consideration.”

The Tower of London, originally a castle, had been used as a treasury, public records office, and a prison. It was also where traitors were traditionally executed.

At dawn on November 6, Assistant Provost-Marshal Lord Athlumney escorted the doomed man out of his cell. Lody held his hand out, “I suppose that you will not care to shake hands with a German spy?”

“No,” Athlumney replied as he took Lody’s hand. “But I will shake hands with a brave man.”

He was executed at the Tower by firing squad – the first man in 167 years. He was the only German spy to receive a trial in either world wars.

Interestingly enough, Lody’s execution violated British law. The courts amended that situation after his death.