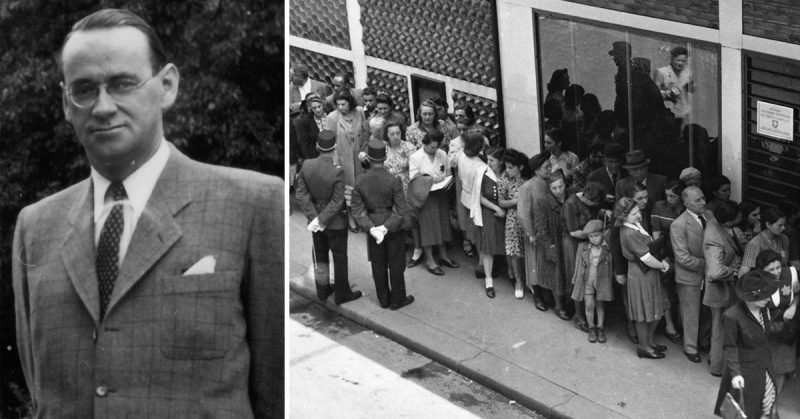

When thinking about the occupation of Hungary by the Nazis in the Second World War, Carl Lutz is not a name that resonates with many people — but it should.

This courageous diplomat was a Swiss version of Oskar Schindler. During his tenure as Swiss Vice-Consul in Budapest, he helped close to 10,000 Jewish children emigrate from Nazi-occupied Hungry. He saved over 62,000 Jews in total.

Who was this man who managed to save more people than almost anybody else during the Holocaust? And how is it that we know nothing about him? For years, this man’s feats have remained in obscurity. It was only long after his deeds that his fellow Swiss finally recognized his achievements.

Moreover, Carl Lutz’s efforts remain very much in the shadow of the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who achieved world fame with his activities to save thousands of Jews. However, Lutz’s work in Budapest was the largest civilian rescue operation for Jews during the Holocaust.

Carl Lutz was born into a Methodist family in Walzenhausen in the Swiss mountains of the Canton Appenzell on March 30, 1895. He was the archetypical Swiss man in that he was a multi-faceted character. On the one hand, he was introverted and religious; on the other, he displayed a penchant for adventure and the unexpected.

His father owned a sandstone quarry in Appenzell. When he was only 14 years old, his mother died of tuberculosis. By the time he was eighteen, he had moved to the USA where he lived, studied, and worked for more than 20 years.

In 1920, Lutz started work for the Swiss Consular Corps at the Swiss Legation in Washington DC.

Lutz climbed the ranks and became Chancellor of the Swiss Consulate in Philadelphia in 1926, and later in St Louis.

In 1934, he met his first wife, Gertrud Fankhauser. They were married in 1935 after he left the USA and became the Swiss Consulate General in Jaffa (which was then Mandatory Palestine). It was in Jaffa where he would, for the first time, encounter hatred towards the Jews when he witnessed a defenseless Jew being lynched by an Arab mob.

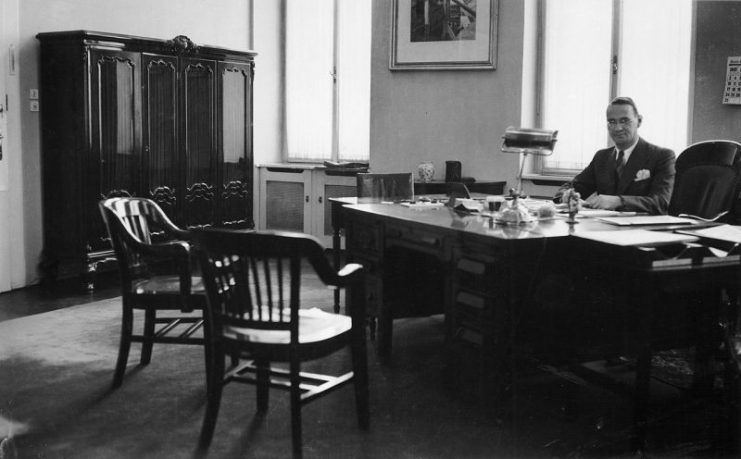

His life’s voyage then took him to Budapest in 1942 where he became the Swiss Vice-Consul to Hungry.

Hungarian Jews were not as persecuted as, say, their brethren in the Netherlands, Poland, and France. While they did suffer from limitations to their political and economic activities, they were spared the mass-exterminations witnessed in other parts of Europe.

So far, Adolf Hitler had left Hungry alone. He was more than happy with the Hungarians’ behavior as a model ally, supplying troops for the invasions of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union.

However, when the Führer discovered that the Hungarians had been conducting secret armistice negotiations with the Allies behind his back, he changed his tune. Germany invaded Hungry in March 1944, and the country was annexed to the Third Reich.

Almost immediately after the Germans had marched into Hungry, the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” was put into full effect. Tens of thousands of Jews, Roma, and other Nazi-decried undesirables were rounded up and deported to the extermination camp at Auschwitz.

Although the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem honors a number of diplomats who — for example, in Paris — issued visas to Jews to prevent their deportation, nowhere else was the number of those rescued from mass murder as high as in Budapest.

Both Carl Lutz and his wife not only issued passports but also hoisted the Swiss flag above houses in order to place their inhabitants under diplomatic protection.

Despite the close alliance with Nazi Germany, the Hungarian government under Miklós Horthy had previously refused to conduct mass deportations. However, after the German invasion, this practice was implemented with great brutality.

Out of the approximate 800,000 Hungarian Jews, about 565,000 were murdered in Auschwitz. More than 424,000 of them were deported within the space of only 56 days. The number would have been even higher were it not for men like Carl Lutz.

The German occupation in Hungary was similar to that of Denmark. The Hungarian government was not dismantled after the German invasion. Despite the presence of German troops presence, the Hungarian state functioned almost as before.

Horthy continued to regard himself as head of state. In this position, in July 1944, he was able to stop the deportations for a while. However, this action should not be misconstrued as a sudden spell of humanitarian compassion. Rather, Horthy was acting in his own interests because he believed in the eventual defeat of the Axis powers.

He wanted to expand his negotiating powers and avoid jeopardizing relations with the Allies after the war.

During this time, Carl Lutz continued to work tirelessly in his mission to save as many Jewish people as he possibly could. He negotiated with the Hungarian and Nazi authorities, even reaching as high up as Adolf Eichmann, who once said that he should be shot. Fortunately, that threat was never acted upon.

But Lutz’s most ingenious invention was the “Schutzbrief” or the “Protective Letter.”

CC BY-SA 3.0

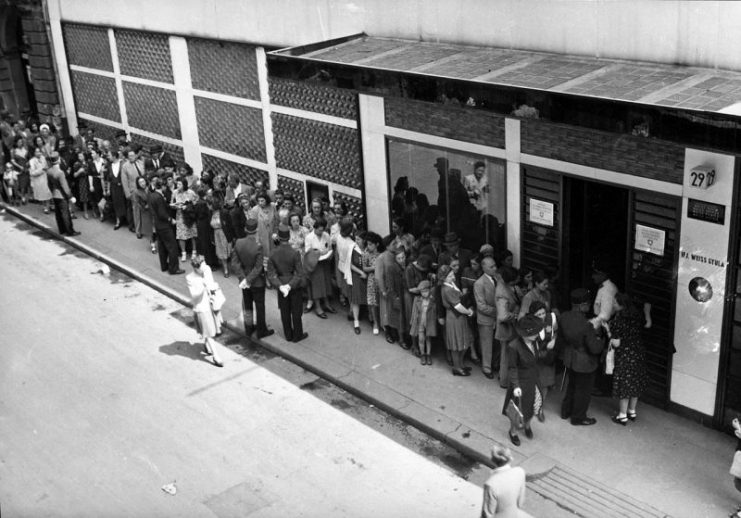

Since the USA and the UK had no diplomatic representation in Hungry, Lutz acted in their capacity as a wartime representative. He shrewdly used this position to create an emigration certificate to British-controlled Palestine. The protective letter for Jews numbered in their thousands and prevented deportation to the death camps.

Another one of his clever ideas involved him extending diplomatic protection to up to 76 buildings in Budapest. By using ingenious twists in diplomacy and the tenets of the Geneva Convention, he managed to create havens that housed and fed the Jews.

It was in one of these establishments, formerly called the Jewish Agency for Palestine, located in the “Glass House” and renamed to the Swiss Legation’s Emigration Department, where he met his second wife and the mother of his adopted daughter Agnes.

Carl Lutz was indefatigable. At one point, he dove into the Danube to save a Jewish woman after members of the Arrow Cross Party (fascist Hungarians) had shot her. Lutz helped the bleeding woman reach the quay, which bears his name, Carl Lutz Rakpart, to this day.

He then promptly addressed the man in charge and said that the woman was under Swiss protection. He departed the scene with his charge, leaving a stunned group of fascists behind him. They had been too afraid to confront such an eloquent man whom they presumed was someone important.

“The scope of his actions I only recognized much later in their full dimension,” explained Agnes Hirschi, the Jewish girl Lutz adopted after the war when he married her mother, Magda Grausz. During the months when she lived with Carl Lutz and his second wife, she was shielded from the events taking place in the outside world.

But that would soon change as the Nazis escalated their killing and persecution.To this day, Agnes Hirschi hates the darkness. She survived the end of the Second World War in a cellar in Budapest. For weeks, she and 30 other people who were in there did not see the light of day.

“I need the light,” said Hirschi during a later interview. She then went on to explain how it had been in January 1945, living in the bomb shelter under the burned-out building of the British Legation in the Hungarian capital. The fuel for the oil lamps and the food had gradually run out. “Our situation was very precarious.”

In the final weeks of the war, when Budapest faced devastating air raids, no one could leave the dark basement. Gertrud Lutz, Carl’s wife at the time, had taken very good care of the situation. However, survival became harder with each passing day, especially in the exceptionally cold winter of 1944-45, when islands of ice floated on the Danube.

Hirschi remembered the hunger and fear that spread through the basement. Carl Lutz had also become more nervous and skinny.It was almost a miracle that the then seven-year-old was in that basement, and even more so that she was still alive at the beginning of 1945. She owed her life to Carl Lutz.

After the war, Lutz divorced his wife Gertrud and married his Jewish maid, Magdalena Grausz. He adopted her little daughter Agnes, who was then still called Agi Grausz.

After the war, Carl Lutz’s heroic deeds became more of a bane than a boon for the rest of his life. Back in Switzerland, instead of standing ovations and recognition of his herculean humanitarian effort, the diplomat received an official reprimand for his actions in Budapest.

There wasn’t even anybody to greet him at the Swiss border when he returned — he was merely asked whether he had anything to declare.He and his first wife did gain some recognition for their deeds during the Second World War. Both of them were awarded the title “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in the name of the Israeli government.

In addition, Carl Lutz was nominated several times for the Noble Peace Prize although he was never awarded the accolade.

Lutz died in Bern, Switzerland, in 1975, a somewhat confused man. According to his adoptive daughter, he never understood why he had been denied recognition for his extraordinary achievements, especially by the Swiss.

His daughter, Agnes, made it her life’s mission to honor the memory of her father, not just because she promised him on his deathbed, but also out of personal gratitude.

It took another 20 years until a significant biography was written about him: Carl Lutz und die Juden von Budapest (published in English in 2000 as Dangerous Diplomacy) by Theo Tschuy.

Moreover, a string of much-deserved tributes followed after his death. It is just so sad that, apart from the Israeli recognition, such a great man was only posthumously awarded on an international scale and not during his life.

Here is a list of tributes dedicated to the hero of Budapest:

- 1963, a street in Haifa, Israel, was named after him.

- 1965, Lutz was the first Swiss national named to the list of “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem, Israel’s memorial to the Holocaust.

- Cross of Honor, Order of Merit, Federal Republic of Germany.

- 1991, a memorial dedicated to Carl Lutz was raised close to the old Budapest ghetto.

- 2014, George Washington University in Washington, DC, posthumously honored Carl Lutz with the President’s Medal in a ceremony attended by his stepdaughter Agnes Hirschi and various international dignitaries.

- A street in Jerusalem, Israel, was named after him.

- In 2018, a meeting room in the West Wing of the Federal Palace of Switzerland in Bern, Switzerland was renamed the Carl Lutz room.