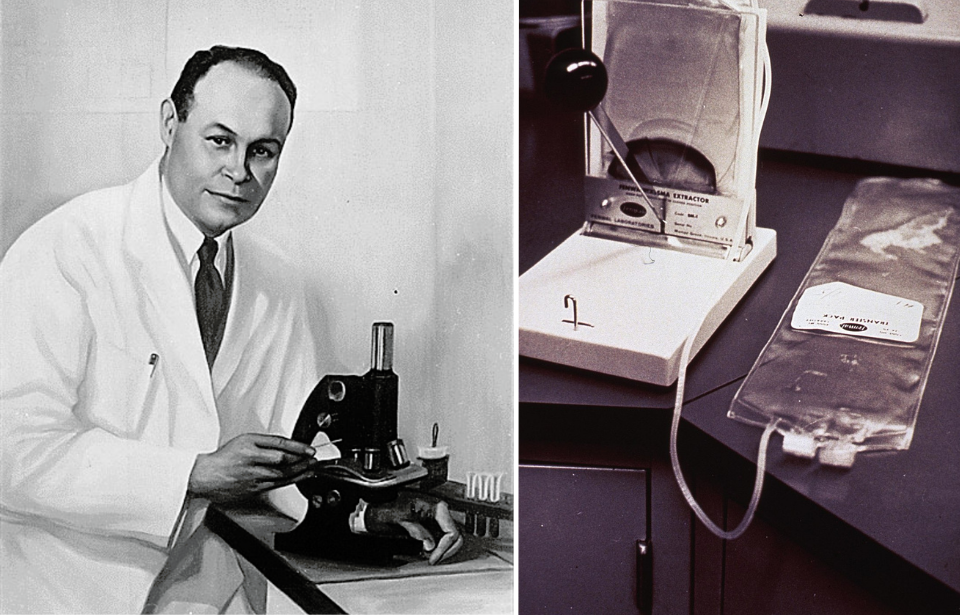

It’s long been known that giving soldiers blood transfusions increases their ability to live through traumatic injuries. What many might not realize is that the method with which blood and plasma are transferred between locations was the brainchild of Charles R. Drew, an African-American surgeon.

A rising star in the medical profession

Charles R. Drew was born in Washington, D.C. in 1904. After finishing college, he spent two years working as a professor of biology and chemistry, football coach and the first athletic director at Morgan College in Baltimore, before attending medical school at McGill University.

During this time, Drew worked with John Beattle, who was looking into a possible connection between blood transfusions and shock therapy. It became clear that the best way to treat victims of shock was to give them a blood transfusion, but there was an issue: there was no successful way to transport or store blood en masse.

Following his graduation from McGill, which earned him a Doctor of Medicine and Master of Surgery degree, Drew continued his education. In 1938, he was granted a Rockefeller Fellowship and went on to study at Columbia University in New York City, where he trained at Presbyterian Hospital.

While at Columbia, he wrote his doctoral thesis, Banked Blood: A Study on Blood Preservation, during which he realized plasma could be preserved longer by de-liquefaction – the separation of blood from its cells. When the time came to use the plasma, it could be returned to its initial state through reconstitution.

In 1940, his findings earned him his Doctor of Science in Medicine degree.

Recruitment by Blood for Britain

In late 1940, Charles R. Drew was recruited by John Scudder and E.H.L. Corwin to create a prototype program around blood storage in the United Kingdom. He was able to apply the research from his university thesis and further develop his knowledge of the topic.

Drew understood plasma extraction required centrifuging and sedimentation. Once that was complete, the plasma was pooled under air and ultraviolet lighting conditions, before being cultured for bacteria. An anti-bacterial called Merthiolate was then added, after which the batches were tested weekly. After diluting with a saline solution and completing a final bacterial test, the plasma was packaged and ready for shipping.

Drew was sent to New York City, where he served as the medical director for Blood for Britain, an organization focused on aiding the British by sending blood from the US to the UK. He ensured hospitals conducted clean transfusions, and during this time created “bloodmobiles,” refrigerated trucks that enabled blood to be transported greater distances. He also set up a central location for donors to give blood.

The Blood for Britain program was a success during its five months. It’s estimated nearly 15,000 people donated blood, resulting in the collection of over 5,500 vials of plasma.

Work with the American Red Cross

In February 1941, the American Red Cross recruited Charles R. Drew as the director of its first blood bank, earning him the title of “Father of the Blood Bank.” The program supplied blood and plasma to the US Army and Navy.

While it accepted blood from both White Americans and African-Americans, the latter was stored separately. This didn’t sit well with Drew, who objected the policy, which remained in place until 1950. In protest, he resigned from his post in 1942.

Drew’s work throughout the course of World War II is credited with saving thousands of soldiers’ lives. It also changed the way blood was banked in the United States and standardized its long-term storage, techniques which were adapted and used by the American Red Cross.

A tragic death

On April 1, 1950, Charles R. Drew was travelling with three other African-American physicians to the annual Tuskegee clinic. He was tired, as he’d spent the previous night working in an operating theater. The resulting exhaustion caused him to lose control of the car. After somersaulting three times, the vehicle came to a stop.

While the three other physicians received only minor injuries, Drew’s leg was caught below the break pedal, resulting in serious, life-threatening injuries. By the time paramedics arrived on scene, he was in shock and barely alive, due to the amount of blood he’d lost. He was pronounced dead 30 minutes after arriving at Alamance General Hospital in Burlington, North Carolina.

Charles R. Drew was laid to rest at the Nineteenth Street Baptist Cemetery in Washington, D.C. on April 5, 1950. At the time of his death, he was the Head of the Department of Surgery and the Chief of Surgery at Freedmen’s Hospital at Howard University.