Since its inception, the VC has been awarded 1,358 times to 1,355 men. And no, there is not a typing error in that sentence. Three men managed to earn this highest of awards twice. It seems like an impossible feat. And yes, it involves unsurpassable bravery on the recipient’s part.

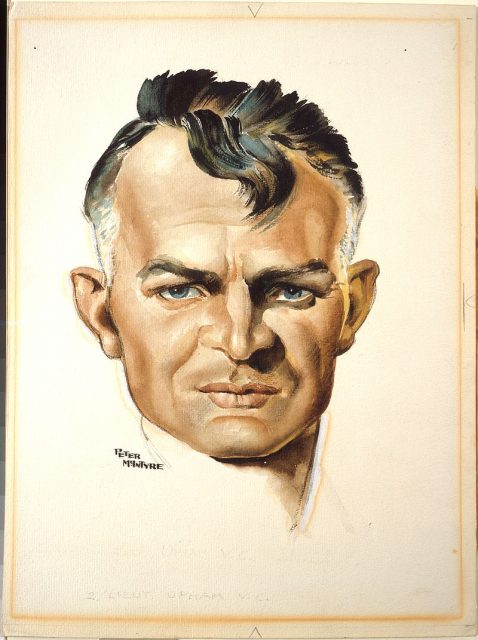

Captain Charles Upham was the only combat soldier to be awarded the Victoria Cross twice. Although no less impressive, the other two dual-recipients, Captain Noel Chavasse and Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Martin-Leake, were both doctors in the Royal Army Medical Corps and got the awards for rescuing the wounded under fire.

The warrior shepherd

Charles Hazlitt Upham was born on September 21, 1908 in central Christchurch in New Zealand. He was the son of John Hazlitt Upham, a lawyer, and his wife, Agatha Mary Upham née Coates.

The young Upham attended Waihi boarding school near Winchester, South Canterbury in the years from 1917 to 1922. Later, he went on to Christ’s College, Christchurch, from 1923 to 1927. He earned his diploma in agriculture at the Canterbury Agricultural College in 1930.

He went to work as a sheep farmer and soon became a manager, after which he worked for the New Zealand government valuing farms. In 1938, Upham had his first brief encounter with the Victoria Cross when he met his wife Mary (Molly) Eileen McTamney, who was a distant relative of the aforementioned Captain Noel Chavasse.

They became engaged a year before Upham joined the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force that was sent to Europe to help fight in World War II. His fiancé soon followed as a nurse for the Red Cross.

By March 1941 Upham, after rising to the rank of sergeant, was fully commissioned as a lieutenant after having been persuaded to join the Officer Cadet Training Unit.

CC BY-SA 3.0

Thus it was as an officer that Upham would receive his VC in Crete in May 1941. During an attack on Maleme Airfield, Lieutenant Charles Upham led his platoon against a heavily and well-organized enemy position. He moved across 3,000 yards under heavy enemy fire, in the process destroying several enemy posts. He and his men were held up on three occasions.

He grabbed a bag of grenades, his weapon of choice, and assaulted a German machine-gun nest, dispatching eight enemy paratroopers. Then he destroyed another machine-gun position before moving to within 15 yards of a Bofors anti-aircraft gun and rendering it inoperable.

When it was time for him and his men to withdraw, Upham helped carry away the wounded to safety under constant enemy fire. Once he and his men were safe, he was given the order to rescue an isolated unit.

With only a corporal for support, Upham went off in search of the soldiers, covering 600 yards while under fire and killing two Germans before locating the lost unit. If it had not been for him, the men would have certainly perished.

Charles Upham continued fighting over the following days despite sustaining wounds to the shoulder from grenade shrapnel as well as a bullet to the foot. He advanced with his platoon, himself drawing enemy fire, until they managed to kill over forty German soldiers.

When his men were ordered to retire, he sent them back under the command of the platoon sergeant while he went off to warn other men that they were going to be cut off by the Germans. He then fought off two German troopers by placing the barrel of his rifle in the fork of a tree because he had lost the use of one of his arms.

Despite suffering from dysentery, during the retreat from Crete Upham climbed the side of a 600 feet deep gorge—looking like a skeleton because of the illness, as one commanding officer remarked. He positioned himself in readiness, and with a Bren gun he held off a force of 50 Germans, killing 22. He never wore a steel helmet like his comrades, claiming that they never fitted properly.

The VC citation for his bravery ended with these words: “He showed superb coolness, great skill, and dash and complete disregard of danger. His conduct and leadership inspired his whole platoon to fight magnificently throughout, and in fact, was an inspiration to the Battalion.”

When Upham was informed of the award, he merely said, “It’s meant for the men.”

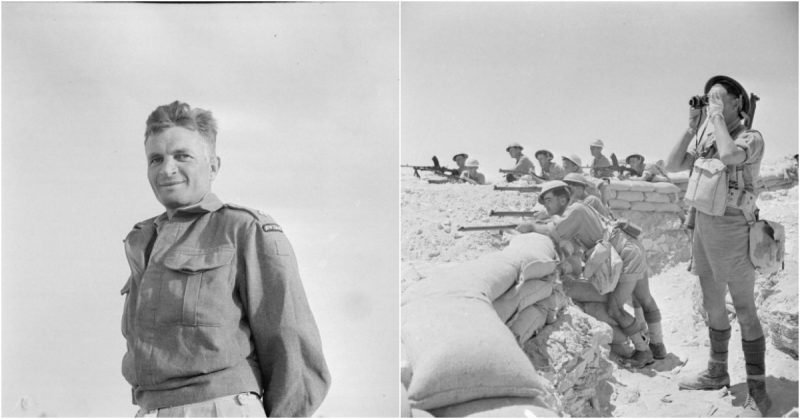

Almost precisely a year later, during actions on July 14-15, 1942, the now newly-promoted Captain Charles Upham again displayed unsurpassable courage during the First Battle of El Alamein in Egypt.

The tale of his exploits starts with the customary pluck and panache we have come to expect from Charles Upham. During the defense of Ruweisat Ridge, he dashed forward under heavy enemy machine-gun fire and tossed grenades into a truck full of Germans.

Captain Upham’s platoon formed a part of the rear guard. When he was given the order to send an officer forward to report to the commander of the advance division, he decided to go himself. Armed with a captured German machine gun and driving a jeep he advanced, encountering much enemy resistance along the way.

Over two days, Upham destroyed a German tank and several machine-gun nests even though his arm had been broken by a shot to the elbow. He never left his post, incessantly rallying his men to greater feats. His leadership resulted in the British and Commonwealth forces holding off the Germans and Italians.

After the skirmish, he was taken away to have his wounds treated. However, the moment his injuries were dressed, he rejoined his men in the fighting. He fought on until he was shot in the legs and could no longer walk. Ultimately, the enemy overran his position, resulting in his capture.

Photo by Mattinbgn CC BY SA 2.0

In captivity, the Italian doctor treating his arm recommended that it be amputated to prevent gangrene, as there was no medication to ward off infection. Upham vehemently fought off such attempts because he knew that such an operation without anesthetics often resulted in death. In the end, a fellow POW who was also a doctor saved him from that fate.

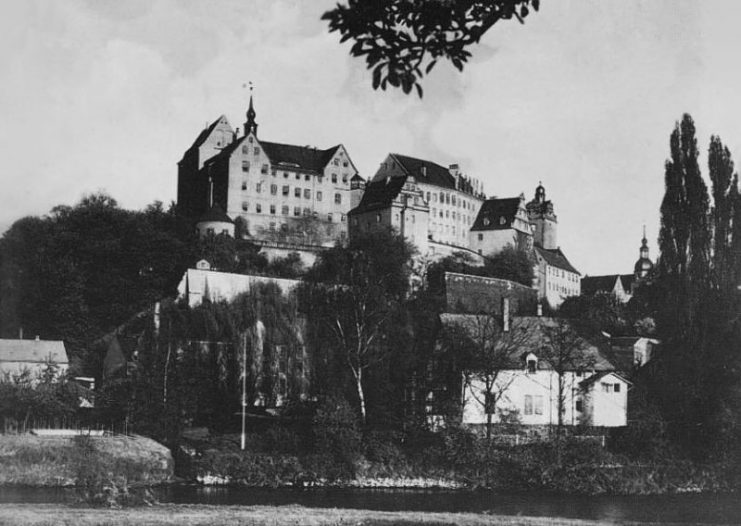

Upham’s multiple escape attempts are yet more extraordinary feats of bravery, some of them reckless, that took place before his transfer to Colditz Castle in Germany, the infamous POW prison dedicated to captured Allied officers. On one occasion, for example, he attempted to escape from a prison camp in broad daylight.

He eventually got entangled in the barbed wire surrounding the camp. The prison guard who was first on the scene held a pistol to Upham’s forehead and threatened to shoot him. Upham merely stared back at him and casually lit a cigarette.

Charles Upham finally ended up in Colditz Castle, where he remained until the Americans liberated it. He was so eager to get back to what remained of the war that he had the Americans equip him so that he could join their unit. But despite being prepared, he was ordered back to England where he was reunited with his fiancé Molly. They finally married at New Milton in Hampshire on June 20, 1945.

Photo by Terry Macdonald CC BY SA 3.0

During his time in England, Captain Charles Upham attended the investiture for his first VC by King George VI on May 11, 1945. Not long after the ceremony, the King was approached by General Howard Kippenberger with the recommendation for a second VC for Upham.

The King seemed surprised and suggested that a bar, a mark representing a second VC, to the cross would be “very unusual indeed.” He then moved on to ask, “Does he deserve it?” To which Kippenberger replied, “In my respectful opinion, sir, Upham won the VC several times over.”

The legend of Charles Upham continued well into his retirement in New Zealand. When he returned home with Molly, the community had gathered £10,000 to buy him and his wife a farm. He refused the gesture, and the money was instead used to set up the C. H. Upham Scholarship for children of ex-servicemen to study at Lincoln University or the college of Canterbury.

He did get his farm though with a loan. Moreover, he turned out to be quite a successful farmer as well. He lived there with his wife, with whom he had three daughters, until January 1994 when he moved to Christchurch because of his deteriorating health.

The man who was the only combat soldier in the then-British Commonwealth to earn two Victoria Crosses for the “most conspicuous bravery, of some daring or pre-eminent act of valor or self-sacrifice, or extreme devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy” died in Canterbury on November 22, 1994 in the presence of his wife and daughters.

Charles Upham’s funeral was held at Christchurch Cathedral, and the streets of the city were lined with thousands of people. His passing was also commemorated in London, where the people paying their respects were joined by many dignitaries and members of the Royal Family.