History often makes strange bedfellows. After Hitler invaded Russia, Churchill said that he would make a favorable comment about the devil if Hitler invaded Hell.

China is a leading geostrategic competitor with the United States, and they are one of the biggest and oldest communist regimes in the world. This and other factors make them a forgotten ally during World War II and overshadow their huge contribution to freedom.

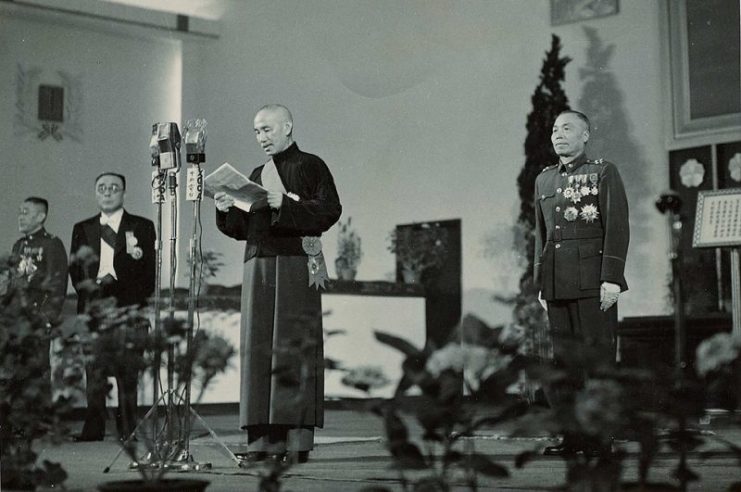

As I discussed in Decisive Battles in Chinese History, by the fall of 1944 the Chinese leader, Chiang Kai Shek, was under a great deal of pressure to give command of the armies to the American liaison in China, General Joseph Stilwell.

Other Chinese generals suggested they strike the Japanese rear. After all, they argued, the Japanese were 212 miles of railroad away from their central supply depot and 447 miles of road away from their core areas. And they were already short of supplies.

But the need to maintain national prestige and defend the Hengyang at all costs prevented what might have been the more effective military option.

China’s Tenth Army was outnumbered two to one, and its defense of Hengyang, led by Fang Xianjue, lasted 47 days and resulted in one of the most ferociously contested battles of World War II.

Hengyang was a key rail junction for at least four nearby provinces. Its loss could open up an avenue of approach to the Chinese wartime capital.

The Chinese soldiers were told that international prestige was on the line and they held every block. They set up earthworks, trenches, pillboxes, and bunkers throughout the urban terrain. They also established hidden machine-gun nests around the city.

The Japanese planned to take the city in two days. They started with a massive artillery barrage, absorbed huge counterattacks, and sent mass human wave attacks against the fortified positions in the city.

Because of a shortage of ammunition, the Chinese adopted a “three don’t” policy: don’t shoot what you can’t see, don’t shoot what you can’t aim at, and don’t shoot what you can’t kill.

This preserved ammunition but also resulted in frequent hand-to-hand fighting. The city was reduced to rubble.

Outside the city, 13 Chinese armies tried to attack the scattered Japanese forces. The Japanese eventually used piles of bodies to scale the Chinese defensive positions.

Ultimately, the Chinese were forced to retreat after running out of ammunition, but their fierce fighting displayed Chinese bravery and the desire to resist the foreign invaders.

The concentrated forces of the Japanese along with failure to coordinate the relief efforts of surrounding Chinese units with the relieving armies meant that Chinese forces were defeated piecemeal.

The political pressure Chiang was under and the strained relationship with Xue Yue illustrated the difficulties Chiang had ruling China during the Nanjing decade and throughout World War II and the civil war. His disagreements with Stillwell represented the conventional but mistaken view of Chinese weakness and supposed lack of desire to fight.

The Battle of Hengyang, or the Fourth Battle of Changsha, was one of the most desperately fought and intense conflicts of the entire war, yet few outsiders seem to know about it or care.

That offensive, which occurred late in the war, was designed by the Japanese to decisively solve Japanese strategic problems.

The Japanese naval fleet and merchant marine were suffering severe losses at the hands of American naval forces, so they wanted to clear and hold a contiguous land route connecting all of Japanese territory from northern China to Indo-China. They also wanted to destroy American bomber bases in China that were pummeling the Japanese homeland.

The campaign that included this battle featured over 500,000 Japanese soldiers, comparable to the German invasion of the Soviet Union. It devastated China and destroyed key industrial areas in Nationalist territory. This operation destroyed an estimated 25 percent of China’s industrial base.

Tax revenue dropped sharply. Critical shortages of food resulted from the loss of grain areas, and the Chinese lost over a million soldiers just in that year.

Chiang wrote, “I’m 58 years old this year, of all the humiliations I have suffered in my life, this is the greatest. . . 1944 is the worst year for China in its protracted war against Japan.”

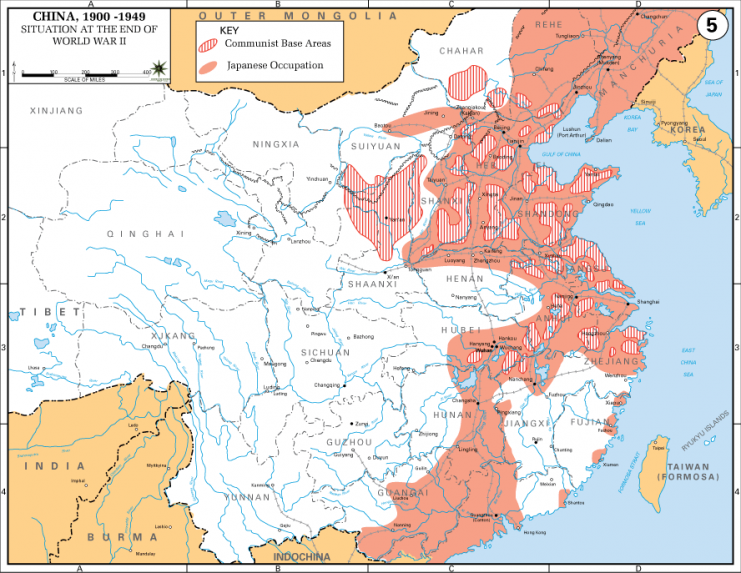

Most critically for postwar China, Chiang had to withdraw the small portion of his forces keeping a wary eye on the Communists. About 30 out of 130 divisions kept them under control.

The Communists took advantage of the absence of Japanese forces in the region to expand significantly. They took over Japanese-based territories and supplies that had been vacated or left behind. The Communists were the true winners of the Ichigo offensive.

Contrary to popular belief, shaped by the memoirs of a bitter General Stillwell, Chiang was committed to fighting the Japanese, not just hoarding material for the eventual fight with the Communists.

As shown by the furious resistance in Hengyang, the active guerrilla war, and the carnage from the Ichigo offensive, the Nationalists fought for their nation and honor to the tune of over a million soldiers dying in 1944 alone.

Chiang bravely resisted Japanese aggression as early as 1937, long before the Western powers joined the war against Japan or Germany. China suffered greatly, fought longer, and fought just as bravely as other Western powers. It even fought the Communists long before the Cold War had started.

Chiang led a fractured government that was beset with jealousy, mistrust, and competing agendas among warlords, Communists, and Nationalists against one of the best armies in the world, and he had to fight with extremely limited resources.

Hue Yue, for example, was a trusted associate of Chiang’s who served in the northern expedition that unified the country, but he and other generals wanted Chiang to fight the Japanese more than the Communists. Hue actually agreed with the decision to arrest him during the Xian Incident (1937) if he didn’t form a united front with the Communists.

This made for rather tense relations, as the political leader had to direct and coordinate strategy throughout the war with a general who supported his arrest.

Strategically, China was put on the back burner during the war. American strategy in the Pacific such as island-hopping, the bombing of the Japanese homeland, and destruction of shipping is credited with winning the war.

But the war in China occupied many Japanese units and exhausted some that were scheduled to assist in Japanese offensives in the Pacific, such as the Battle of Guadalcanal (August 1942–February 1943).

After the war, Chinese officials argued that if resources for Pacific island-hopping offensives in 1944 had been given to them, they could have stopped the Ichigo offensive and protected American bomber bases in China. There is merit to this argument, as China actually received a rather small amount of Lend-Lease material until 1945, by which point the outcome was hardly in doubt.

Those arguments about military aid were vigorously disputed by Western analysts, with most viewing China, and Chiang in particular, as backward, feudal, and corrupt. This is simply inaccurate and unfairly judging Chiang.

He led vigorous training programs supervised by German officers before and during the early parts of the war. (This led to the somewhat ironic situation in which German advisers were placed in Chinese units fighting their future Japanese allies).

He had rather strong ideas for reform, but because of a violent insurgency and then an aggressive world war on his doorstep, he was unable to implement vital changes like land reform.

Stillwell’s disagreement with Chiang, the many journalists who heaped praise on what they viewed as Communist reformers, and the Communist winners of the civil war helped solidify the Western view of China as an incompetent military regime, but the Chinese executed the war using various strategies to mobilize support, maintain armies, and fight battles.

Nationalist propaganda looked at various national heroes, ranging from Sunzi to Yue Fei to Qi Jiguang to help rally resistance. Their economy sometimes moved to a barter system so the government could get needed funds.

Up until the Ichigo offensive, the Nationalist government stabilized farm production and tax revenues and essentially turned the war into a stalemate.

Figures vary widely, but an estimated ten million soldiers and twenty million civilians were killed in what is sadly and unfairly seen by many historians as a useless Chinese contribution to World War II.

As we consider history it’s important to remember that enemies today are often friends from yesterday and vice versa. China was a vital ally in the war against Communism, fought the Axis powers — and fought bravely — but because of the cruel twists in history such as a bitter American general, hostile American press, and the victory of the Communists in their civil war, their contributions in World War II are largely forgotten.

Read another story from us: Virtually Unpunished – Horrible War Crimes in the “Rape of Nanking”

In assessing potential Chinese threats such as seemingly aggressive behavior in the South China Sea, it’s important to consider more of their history and their potential to be an ally against a resurgent Russia and nuclear North Korea.

At the very least, Americans should remember China’s contribution to freedom by bravely fighting Japan during World War II.