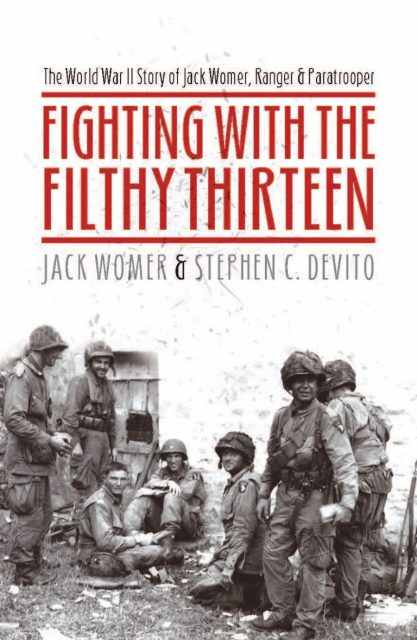

The following edited extract is taken from Jack Womer’s memoir ‘Fighting with the Filthy Thirteen’ about his time spent among the most notorious paratroopers of the 101st Airborne.

On the day before Christmas, the Krauts bombarded us with heavy artillery throughout the afternoon. They stopped for a little while in the evening, and then taunted us by playing Christmas carols and other popular Christmas songs on loudspeakers. Our lines were only about 300 yards away from theirs, so we could hear the music loud and clear.

A lot of guys had been hit during the shelling despite the fact they’d been in their foxholes. Flying pieces of shrapnel would occasionally find their way into a soldier’s body even if he was taking cover. Sometimes artillery shells landed directly in a foxhole and exploded, and instantly killed anyone who was in it. A lot of guys were injured from trees that had been knocked down from exploding artillery. A tree would fall over a foxhole, and the limbs or large branches would drive into the foxhole and penetrate a man’s body.

Whenever the shelling stopped, those of us who weren’t wounded would climb out of our holes to look for wounded soldiers and tend to their needs. This was actually quite dangerous. The Krauts knew that we did this, and sometimes they would resume shelling shortly after they had stopped, to kill or wound the guys who were walking about looking for wounded men.

The cruelest thing that I witnessed the Krauts do throughout the entire war occurred on Christmas Eve, 1944. About seven or eight men from the 506th PIR had been severely wounded from the Kraut shelling. They were in pretty bad shape and needed immediate medical attention if they had any chance of surviving. Even if they could survive, it was obvious that they wouldn’t be able to return to combat duty. They were finished as far as the war was concerned.

A few of us helped the ambulance drivers load the wounded into two ambulances. The ambulance drivers were going to take them back to one of the 101st Airborne’s makeshift aid stations or field hospitals that had been set up behind our lines. The ambulances took off from our lines on a dirt road, and we watched from our position as they drove away. After the ambulances had traveled a few hundred yards we saw them stop. A bunch of Krauts had forced them to come to a halt, and ordered the drivers to get out. We watched as the Krauts mercilessly shot and killed the ambulance drivers and the wounded men, all of whom were unarmed, and siphon the gasoline out of the ambulances. I don’t know whether the ambulance drivers went the wrong way and inadvertently drove into the Kraut lines, or had gone in the correct direction and a few Krauts had penetrated along that dirt road; all I know is that the Krauts killed all of those unarmed men for a few gallons of gasoline.

When a soldier sees his enemy do such things, it creates a desire within him to go out of his way to do the same. Killing is no longer done for purposes of survival or fulfilling a mission, it is done out of vengeance and bitter hatred for the enemy. When we saw this we became filled with rage.

We wanted to leave our foxholes with our rifles, grenades and bayonets, and hunt and kill as many Germans as we could find, as if they were wild animals, not for the sake of winning the war, but to get even.

At one point on Christmas Eve the Krauts shelled us with “Christmas cards.” these were just propaganda leaflets written to convince us that corporate America and our own military were our real enemy, and that we should join forces with the Krauts and take sides against the United States.

The Krauts placed these leaflets inside of blank artillery shells and fired them at us. They were trying to break our spirit and make us give up. But their attempt at trying to frighten us into surrendering didn’t work. None of us gave in to them. They resumed the shelling of our lines with heavy artillery throughout the rest of the evening and until about 2:00 am on Christmas morning. On Christmas day itself they resumed shelling and kept it up for hours. They hit us with some pretty big artillery. When those shells exploded the ground would shake vigorously as if there was an earthquake happening right underneath us. The percussions from the endless stream of exploding rounds rattled every bone and organ in our bodies, and played hell with our nerves.

The artillery barrage shook the hell out of us, both physically and mentally. A lot of men got hit with shrapnel, falling trees or flying splinters from blown-up trees while hiding in their foxholes. They cried out in agony. The rest of us wanted so much to crawl out of our foxholes and help them, but to do so during the artillery barrage would have been sheer suicide.

To endure the shelling, I spent most of Christmas Day curled up and face down in the bottom of my foxhole, praying to God that I wouldn’t get hit.

Later on Christmas Day the weather again cleared, and this allowed our bombers to bomb the hell out of the Kraut positions that had been shelling us. Looking up from our foxholes and seeing our own bombers fly overhead towards the Kraut lines made us feel real good. C-47s also flew overhead and dropped some badly needed supplies on us. I remember many of us collected the parachutes attached to the cartons and cases that were dropped. We cut the parachutes up into long strips and used them as bandaging material for our wounded. We couldn’t keep enough bandages on hand, as there were so many wounded soldiers.

It was pretty rough on Christmas Day. The only food I ate was a ration can of ham and eggs. On every Christmas day since, I think about what we soldiers experienced on December 25, 1944, and how lucky I was not to have been wounded or killed.

On December 26th, the lead division of General George Patton’s third Army arrived from the south and broke the Kraut line that surrounded us. We were no longer surrounded, and our lines were now reinforced by Patton’s first-rate Third Army. Seeing all of those many third Army tanks and troops sure made us happy. While the battle for Bastogne was far from over, this was the beginning of the end for the Krauts as far as their attempt break through the American front with their offensive.

Somehow I never reached my breaking point at Bastogne and during the 130 days I spent at the front line. But there were guys who did, including guys that had spent less time in combat than me. When a guy reached his breaking point he was usually pulled from the front as soon as a replacement could be obtained and sent somewhere where he could, hopefully, calm down. While I didn’t “break,” by the end of December 1944, I was at wits end with the war. I wanted nothing more than to go home, return to work at the Bethlehem steel mills, marry Theresa, start a family, and put the war completely behind me. I wrote to Theresa constantly expressing exactly how I felt. But I couldn’t go home just yet.

Jack Womer passed away in 2013.

His memoir ‘Fighting with the Filthy Thirteen’ is now available in paperback on Amazon.