During World War 2, Churchill and Roosevelt met in locations such as Tehran, Cairo, and Moscow, locations that would have them traveling very close to, or over, enemy territory.

Why did the countries take such risks with their leaders?

Unlike modern-day politicians, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his British counterpart, Winston Churchill, did not have the luxury of traveling in state-of-the-art jets to wherever they needed to go. There were no anti-missile defense systems or the like to keep the Nazis away.

For these two gentlemen, a transatlantic flight was risky and rare. Furthermore, the Germans did their utmost to get their hands on enemy leaders, especially their arch-nemesis Churchill.

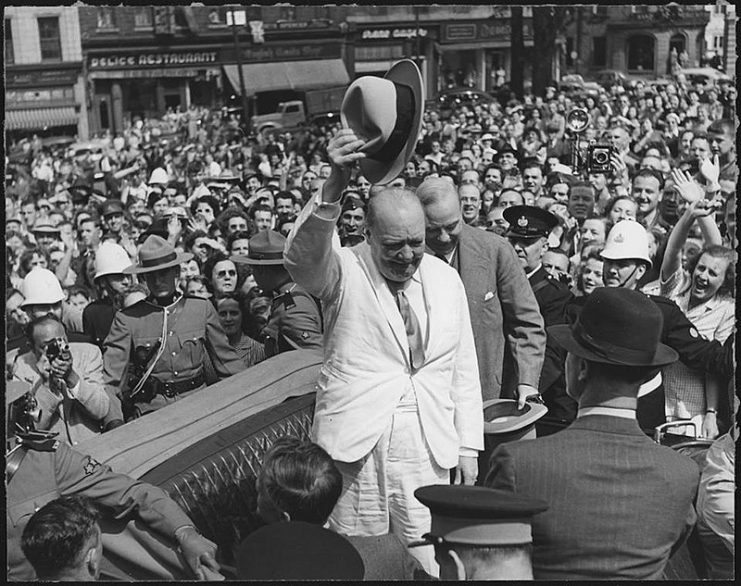

And still, Winston Churchill traveled over 100,000 miles in 25 trips, sometimes spanning entire continents during the Second World War. This was a feat far greater than any other wartime leader. That said, Churchill did get an earlier start with the Americans only joining the war at the end of 1941.

The British Prime Minister was always fearless, at times getting perilously close to dangerous war zones. In spite of this, he assiduously believed in face-to-face negotiations no matter the risk to his life.

With a dry sense of humor, Winston Churchill often traveled using the alias “Colonel Warden” for security reasons.

Aged 65 at the onset of the war, Winston Churchill was not a young man. Furthermore, he was not somebody one would describe as physically fit – the Prime Minister loathed any sports.

His attitude was beautifully summed up when somebody asked him how he had reached the impressive age of 92. Churchill responded, “Absolutely no sports, just whiskey, and cigars.”

Despite his somewhat controversial view on Imperialism and his endorsement of human rights abuses in the colonies, we all know Winston Churchill as the man who stood up to Adolf Hitler.

During Britain’s “Darkest Hour” he never surrendered – he gave hope to a nation that stood on the edge of a precipice. His first speech as Prime Minister on May 13, 1940, exemplified the man’s spirit and drive.

“We are in the preliminary stage of one of the greatest battles in history … I would say to the House as I said to those who have joined this government: I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat. We have before us an ordeal of the most grievous kind. We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering.”

With those words, the United Kingdom’s leader dove into action. Less than a week after having been offered the King’s commission to his office, Churchill departed for France.

These were perilous times. The Nazi juggernaut had already advanced on Paris. It would be the first of several trips undertaken by the British leader to France before the French capitulation.

But would the danger stop him? Not a chance!

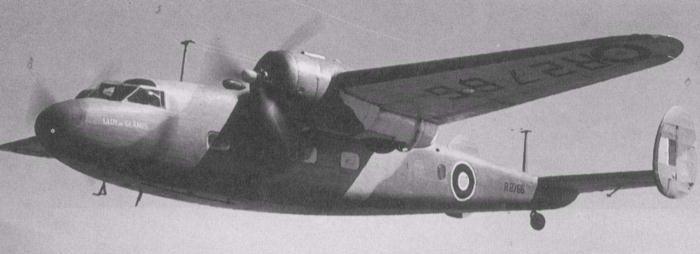

Instead, a squadron of RAF fighters escorted Churchill’s de Havilland D.H. 95 Flamingo plane to wherever he needed to be in France. On one such occasion, Major-General Edward Spears, the Prime Minister’s attaché to the French Prime Minister, wrote about Churchill’s review of the Hurricane pilots:

“Churchill walked towards the machines, grinning, waving his stick, saying a word or two to each pilot as he went from one to the other, and as I watched their faces light up and smile in answer to his, I thought they looked like the angels of my childhood. … These young men may have been naturally handsome, but that morning they were far more than that, creatures of an essence that was not of our world: their expressions of happy confidence as they got ready to ascend into their element, the sky, left me inspired, awed and earthbound.”

Flying Officer Gordon Cleaver, one of the Hurricane pilots, remembers events somewhat differently, describing his comrades as “just about as hungover a crew of dirty, smelly, unshaven, unwashed fighter pilots as I doubt have ever been seen. Willie, if I remember right, was being sick behind his aeroplane when the Great Man arrived and expressed a desire to meet the escort. We must have appeared vaguely human at least, as he seemed to accept our appearance without comment, and we took off for England.”

Churchill continued flying to France until the very end, despite the risk to his person. Miraculously avoiding the then dominant Luftwaffe, he pursued the fleeing French leadership all the way to Tours prior to French capitulation – the UK was alone against the Nazis.

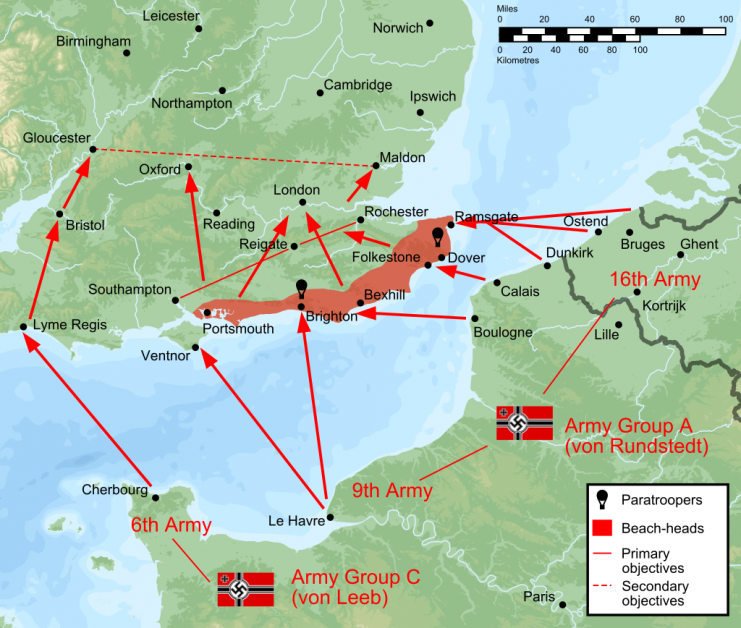

After the Nazi occupation of France, Winston Churchill’s full focus turned to the Home Front. The Battle of Britain had begun. Herman Goering hurled the full force of the Luftwaffe at Britain’s cities and production facilities in the hope of shattering British morale. He failed.

Between July and October 1940, the Third Reich and the United Kingdom pitted the full might of their air forces against each other until, ultimately, the British prevailed.

![German Do 17 bomber and British Spitfire fighter in the sky over Britain. December 1940.[Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1969-094-18 / Speer / CC-BY-SA 3.0]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2016/07/39.-640x430.jpg)

[Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1969-094-18 / Speer / CC-BY-SA 3.0]

When Adolf Hitler finally directed his full attention to the East and the Soviet Union in June 1941, Churchill could finally do what he had always planned.

Since it had been over a year since his last trip abroad, it was time for Winston Churchill to expand his horizons from short Channel hops to places further afield.

Operation Sea Lion

However, in a way, Churchill had already started his next voyage in his mind. He and his American equivalent, FDR, had already exchanged letters that would put any ardent modern-day “WhatsApper” to shame. In total, the two leaders exchanged an estimated 1,700 letters and telegrams during the war.

The close friendship of the two men is wonderfully described in Winston Churchill’s quote: “Meeting Franklin Roosevelt was like opening your first bottle of champagne; knowing him was like drinking it.” It’s safe to say the two men got along.

FDR and Churchill had already been holding secret talks about US military intervention since early 1941. It was the time for the two men to talk face to face and so RIVIERA was born – a top-secret mission for an Atlantic Conference in Newfoundland was in the offing.

However, the Atlantic Ocean was the domain of the Nazi U-boat, which had already done an extremely efficient job of sinking thousands of tons of British shipping.

Furthermore, Churchill and his entourage had to get around German naval surface ships and the dreaded long-range Focke-Wulf planes, also called the “Scourge of the Atlantic” for the havoc they wreaked on British shipping. Luckily, the British were having considerable luck with Nazi codes, invariably getting a heads up concerning German activity.

Ever the optimist, Churchill decided to go ahead with the meeting despite the risks. He embarked on HMS Prince of Wales along with an escort of destroyers.

As it happens, the German warships Tirpitz, Scharnhorst, and Gneisenau were in port fitting out and the U-Boats were too slow. In effect, the trip was far less dangerous than initially predicted.

The famous meeting between FDR and Churchill in Placentia Bay resulted in the “Atlantic Charter.” The agreement was pivotal for the British war effort – it outlined the post-war rules and the US’s support of the UK.

The return home was, in imitation of the outbound voyage, uneventful but sadly many sailors of HMS Prince of Wales would drown four months later as the result of a Japanese attack.

Later in the year, in December 1941, Churchill once again crossed the Atlantic after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and attacked British possessions in South-East Asia. This time, the indefatigable Prime minister traveled on board HMS Duke.

The Prince of Wales sister ship reached Hampton Roads Virginia safely. Only gale force winds made the voyage bothersome; the Nazis were never a threat.

However, Churchill did encounter some danger during this voyage. It happened during his recuperative stay in Florida after a mild heart attack. Apparently, a rather large shark was spotted off the coast. After that, the PM decided to stay in the shallows for the remainder of his stay.

As well as resulting in the Allied formulation of the future war strategy against the Axis powers, this most recent trip had another pivotal impact: Churchill discovered a whole new way of getting around.

On January 14, 1942, Churchill’s party left Norfolk Naval Base for Bermuda to meet up with the Duke of York. During the four-hour flight, Churchill got to know the aircraft a lot better. Captain John Kelly Rogers even let the Prime Minister take the controls for a while.

Churchill then inquired whether it would be possible to make the journey from Bermuda to the UK. The pilot affirmed that it could be done – and they did.

From then on, for the larger part, Winston Churchill took to the air. It was perfect for him: he loved flying and hated to waste time. Furthermore, as the war progressed, the Luftwaffe no longer had control of the air.

Six months after Bermuda, Churchill undertook his only transatlantic round-trip during the war. BOAC’s Bristol carried Churchill and his party from Stranraer in Scotland to Baltimore, USA, then 14 days later back to the UK via Newfoundland.

In August 1942, during the heat of the war in North Africa and the Mediterranean, the Prime Minister flew to the Middle East. After that, he went on to Moscow to meet Stalin for the first time. The two leaders got along swimmingly thanks to copious amounts of booze.

The sky would beckon Churchill many more times in 1943. He flew from the UK to Casablanca (Unconditional Surrender Conference with FDR), with ensuing stops at Nicosia, Cairo, Tripoli, and Algiers. Again, it must be said that the Mediterranean was still dangerous due to the Italian and German air forces. Then, at the end of the year, FDR, Joseph Stalin, and Churchill all met up in Teheran.

In 1944, Churchill undertook many more trips. For example, he went to the Italian theater around Naples. Later in the year, he went via Naples to Moscow. After D-Day, Churchill traveled to Paris for the first time since the Nazi invasion. Finally, on Christmas Eve, he boarded a Skymaster plane for Athens to mediate in the Greek civil war.

The PM’s 25th and final trip during WW2 was uncharacteristically distant from danger. Churchill spent a week in Bordeaux painting before the final summit in Potsdam, Germany.

Read another story from us: How Churchill Became The World’s Greatest Wartime Leader

As you have seen, Churchill was by far the more active traveler compared to FDR. It is even rumored that the “British Bulldog,” as the Soviets liked to call him, wanted to land in France with the forces of the British Empire on D-Day. The King persuaded his Prime Minister to leave the fighting to younger and fitter men.

For Churchill, danger was never a deterrent – he was a fighter all of his life. For him, meeting face to face, no matter the odds, always superseded personal safety.