Men like Churchill and Lloyd George felt bound to get involved in a battle of ideologies because of their convictions and prejudices as they continued to enjoy the dregs of victory over the Central Powers.

There are several accounts of the moment Brian Horrocks stood in front of the officers of XXX Corps in the cinema at Leopoldsburg to brief them on their upcoming role in Operation Market-Garden in September 1944.

“Gentlemen, this is a story you shall tell your grandchildren and mightily bored they’ll be…” Great stuff, but the event should not define the life of a career soldier like Horrocks because he already had enough stories to amuse any number of listeners.

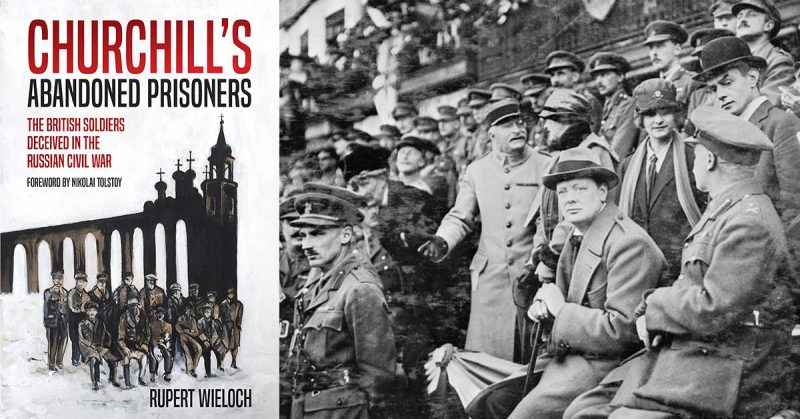

This excellent book by Rupert Wieloch places a younger Horrocks amid the chaos and cruelty of the Russian Civil War in 1919 where a string of adventures included a worrying time as a prisoner of the Bolsheviks.

The author introduces us to a number of British soldiers who were sent to Russia as part of Britain’s support for the Whites attempting to prevent the vast country from falling into the hands of the Red Army. As with many a civil war it was not a simple case of one side against another.

The war included a rainbow of factions opposing the Reds and each other in the quest for power, wealth and territory. The British were not the only nation who made the mistake of attempting to pick sides in a conflict they would have been better to leave well alone.

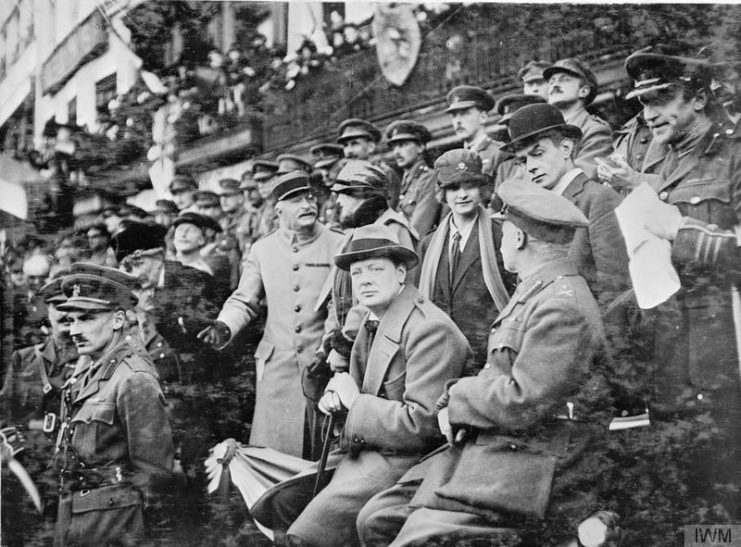

Men like Churchill and Lloyd George felt bound to get involved in a battle of ideologies because of their convictions and prejudices as they continued to enjoy the dregs of victory over the Central Powers.

The British were just part of an international effort in Russia that saw the competing interests of American, Canadian, Czech, Chinese, French, Italian, Japanese, and Polish military men coming up against the ambitions of a bevy of Russian dreamers, schemers and opportunists hoping to gain from the defeat of the Bolsheviks.

There were plenty of people trying to do the ‘right thing’ by not taking sides, but even the idealistic Americans were hindered by differing intentions coming out from the State and War Departments that left the soldiers on the ground seeing no consensus on the strategy to follow.

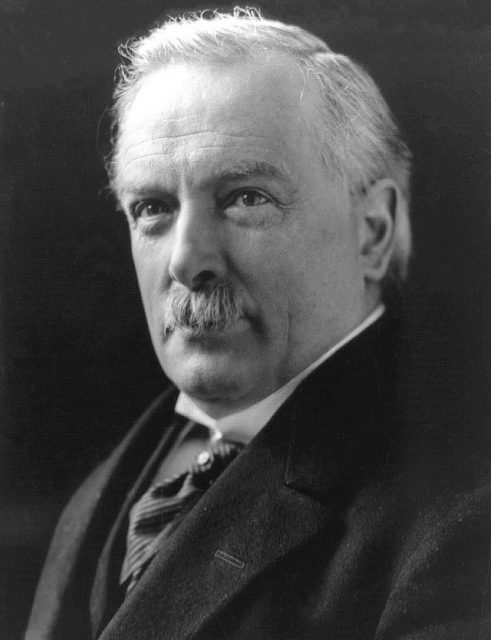

In Britain, Winston Churchill was implacably hostile to the Bolsheviks using his position as War Minister to encourage the use of British troops, money and war materiel to bolster the White Russians he championed. Prime Minister David Lloyd George, slippery as ever, was keen to improve relations with Lenin’s government to foster trade opportunities at a time when his country was flat broke after the trials of the Great War.

Both men would never let inconvenient truths get in the way of their ambitions and to that end neither were afraid to mislead Parliament to get what they wanted.

The British soldiers and sailors swept up in the Russian Civil War were piggy in the middle. We meet Emerson MacMillan, an American of Scottish ancestry moved to fight for the old country in the war against the Kaiser who arrived in time to be sent thousands of miles to face a totally different scenario.

His future wife Dallas Ireland was in Russia, too, working as a nurse. Major Leonard Vining was a sapper officer who had the invidious task of leading a group of Brits who were destined to fall into Bolshevik hands. The author introduces us to a host of characters, including the aforementioned Brian Horrocks, who found themselves in trouble. Horrocks had adventures and made lasting friendships in Russia but also endured the misery of typhus, a disease that killed tens of thousands.

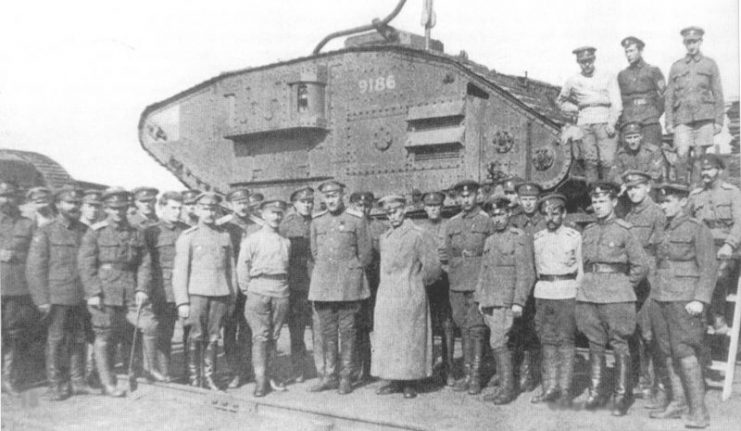

The British operated within territory nominally controlled by Admiral Alexander Kolchak, a one time Polar explorer and naval commander who had become supreme leader of the White government in Siberia. Kolchak’s rule was heavily reliant on foreign military aid, notably British; that saw thousands of troops on all sides wearing British uniform and carrying a mix of weapons and kit paid for with hard cash from London.

Kolchak was in possession of £65 million worth of imperial Russian gold and there is no doubt that his cash strapped foreign allies had their sights on it. Fighting Leon Trotsky’s army was one thing, but the greatest challenge facing Kolchak was his attempt to unify competing forces serving under the White banner. That his failure to do so would lead to the collapse of his realm and his execution seems inevitable when we read of the reality of just how weak and chaotic his regime actually was.

Kolchak held vast swathes of territory from Lake Baikal to the Urals but he was reliant on a tottering railway network to maintain his grip on power and it was this that saw engineers like Vining and MacMillan sent out to keep the show on the road. The scale of the task was too much for the resources available in a country beset by famine, influenza and typhus epidemics in addition to the small matter of a brutal civil war.

Rupert Wieloch’s heroes are typically the stuff of footnotes in bigger stories. A book like this puts flesh on bones we would rarely know but for diligent and enthusiastic research. The terrible canvas of the civil war is the background to a story of endurance and comradeship as the motley band of Brits are shuttled hither and thither witnessing all manner of horrors.

The author presents the grim stuff with care but it is impossible not to wince at the cruelty of a conflict that took place in a bitter Siberian winter. Cynicism is everywhere as competing forces do their best and worst. The reader is presented with a somewhat confusing trail of events but we are soon drawn to discussions far away from Russia where the deals were made that saw the British prisoners released.

The fact is that neither Churchill or Lloyd George came out of this tale particularly well, but it did their ambitions no lasting harm. Just as my allusion to Brian Horrocks’ speech in a cinema in 1944 did not define his full life as a soldier, champions of Winston Churchill might suggest that the lessons of the Russian civil war would help prepare Britain’s wartime leader for the stage that defines him.

An ungrateful and embarrassed British establishment gave no honours to the men who had endured so much for their country and some of the officers were actually demoted to save money while in captivity. Letters and accounts by bit part players such as Emerson MacMillan give us something tangible to take from a conflict that seems too huge and distant to get a grip on from this distance, but there is much to learn here.

Rupert Wieloch has written a genuinely interesting history that provides a useful entry point into the confusion of the Russian Civil War. It is a story that may well leave you not a little angry but it is not totally devoid of happy endings. Our man Emerson married Dallas once they were on safe ground and his fellow prisoners seemed none the worse for their ordeal once they reached good old Blighty.

The futility of what they were trying to achieve in Russia seems obvious a century on, but they were crazy times and the spirit of the chaos is alive and well in this entertaining and quite intriguing read.

Reviewed by Mark Barnes for War History Online

CHURCHILL’S ABANDONED PRISONERS

The British Soldiers Deceived in the Russian Civil War

By Rupert Wieloch

Casemate Publishers

ISBN: 978 1 61200 7533