One war to fight is arguably enough in anyone’s lifetime. Two back-to-back is enough to destroy most people.

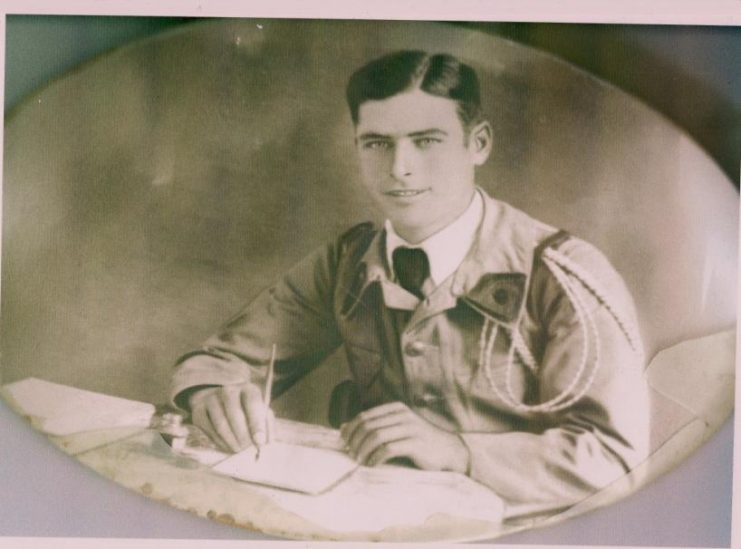

Coming to the end of their second major war, Spaniards Francisco Jeronimo, Justo Balerdi, and Raphael Ramos found themselves in Northern Italy in March 1945, about to undertake one of the most daring raids in the entire history of the British Special Air Service (SAS).

But how did these men from a neutral country end up fighting their second war, soldiering in Great Britain’s elite, hit-and-run regiment? This is the story of these men and others like them. Men who, after fighting in their own brutal civil war to combat fascism, fought to free all of Europe.

In early 1939 the three-year-long Spanish Civil War had come to a close. Fascist leader Generalissimo Francisco Franco controlled all of Spain and for those fighting on the side that lost–the democratic, left-leaning Republicans–there were two stark choices.

They could either stay in Spain and face the wrath of Franco, which invariably meant prison or execution, or they could attempt the long and treacherous trek through the snowbound Pyrenees Mountains in an effort to escape.

The thousands that chose the latter option longed to find freedom and possibly a means to continue the struggle. But they faced an uncertain welcome from a French government that did not want them.

They were imprisoned in “internment camps” in conditions only a little better than the Nazi concentration camps to come. They were fed near-starvation rations and barred from contact with wider French society. The French government hoped such treatment would force the “Spanish Reds” to go home.

However, knowing what they faced if they returned to Spain, many opted to stay put.

French opinion changed overnight after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany on 1 September 1939. France and Great Britain had tied themselves to Poland’s fate, and thus found themselves at war with Germany.

In the Spanish Civil War, Germany had sent troops–the Condor Legions–and warplanes to fight on Franco’s side. Working with the age-old premise that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” the Spanish Republicans and the Allies now had a common cause.

The French also felt that the war-hardened Spaniards languishing in the camps might be useful. Of course, their “freedom” would come with conditions, ones that were beneficial to France.

Such conditions would see thousands die on the battlefields of France, Norway, and Crete, to name but a few. Tens of thousands more would be worked to death in the concentration camp at Mauthausen-Gusen in Nazi-controlled Austria, just for the “sin” of being Spanish Republicans.

In early 1940 the French government went to the Spanish internees with an offer. They could leave the internment camps, but only in one of a few ways.

First, they could join the French military workforce, similar to the British Pioneer corps, and be tasked with manual labor in support of the war effort. Or they could take up contracts with French industry as workers, or become farm laborers in rural areas.

Lastly, they could “volunteer” for the infamous French Foreign Legion (the Legion). The Legion had been created in 1831, “to let any available foreigners assist them [the French government] in any necessary bleeding and dying for La Patrie.”

With war coming, the Legion needed fodder and the Spanish could play their part, as would refugees from all over Europe, including Czechs, Poles, White Russians (anti-communists) and the many Jews who had to fled Hitler’s “Final Solution.”

But in 1939, the Legion’s biggest draft of recruits would be the Spaniards. As a massive bonus, they had one thing the French really hungered for: battle experience fighting against fascism and the Germans.

Thousands of Spaniards “volunteered.” There were, after all, fringe benefits to joining the Legion. Pay and allowances were one benefit. Plus, if the recruit had a family in an internment camp, they also would be freed.

Jeronimo, Balerdi and Ramos decided that their best chances lay with the Legion. If nothing else, it might allow them to take the fight to the fascist enemy once more.

Jeronimo would end up with the 6th Regiment and get posted to Syria. Balerdi and Ramos would be sent to another part of the French colonies in North Africa, serving with another arm of the Legion. It would be three long years until their paths would cross again.

As the war for France grew suddenly very dire, the French recruited the strongest, healthiest, most combat-experienced men who remained in the internment camps directly into the French military. They would now have a chance to prove their mettle.

One of the earliest moments of Spanish glory in the French army was at Narvik, in Norway, in April 1940. Spaniards made up one third of the 3,600 “French” expeditionary forces that went ashore on the 14th, advancing into the teeth of the German invasion.

In the resulting bloody fighting the “French” regiments saw great success, but the cost was a punishing casualty rate. One Spanish company alone lost seventy men, more than half its total number.

Eventually, the surviving units had to be pulled out, to defend France from the German onslaught. In the face of imminent invasion, Spaniards were spread all across the front lines of France, from the borders of Italy northwards to the channel coast.

They would meet the Germans head on, defending places redolent with history, such as Alsace and the Somme. Whole regiments of the French Foreign Legion were cut to pieces by the enemy’s Stuka dive bombers, and lightning artillery, tank and infantry thrusts–all part of the Nazi Blitzkrieg (lightning war). Often the Legionnaires fought with weaponry dating back to World War I, or even earlier.

During the first days of the battle for France, a Spanish workers’ company was digging defenses around a chateau near Tourcoing, on the French border with Belgium.

The French officers fled under constant artillery fire, but the Spaniards that remained entered the chateau. Finding machine guns, rifles and a limited supply of ammunition, they opted to stand and fight.

One of the Spaniards had a large Republican flag hidden under his worker’s uniform. He proceeded to unfurl it, and it was raised above the chateau. A hundred Spanish men prepared to fight and die under their own flag in a French chateau.

By the end of the battle, there were a mere thirty left alive. The German officer leading the assault inquired as to the nature of the flag of these die-hard defenders. He could barely believe the answer he was told.

With the battle for France coming to an end, Spaniards all over France and Belgium hungered to continue the fight, by whatever means possible. But of some 9,000 Spaniards that made it to Dunkirk, less than 2,000 would make it across the Channel.

For those trapped in France, fortune was now to take a much more sinister turn: if caught, they faced the full brunt of the Nazi concentration camp system.

They would not be treated as prisoners of war (POWs) like the French soldiers they had fought alongside. Instead, they were transported to some of the deadliest work camps the Germans had to offer.

Most found their way to Mauthausen. Spanish women, children and old men would join the soldiers as they were worked to death in Mauthausen’s granite quarry, climbing the 186 steps of the “stairs of death” while carrying huge boulders on their shoulders.

Of the 10,500 known Spaniards who entered Mauthausen, eighty percent would perish.

Jeronimo, meanwhile, found himself in a state of limbo. Syria, a French colony, had now to decide which side it was allied to: either the Vichy Government of France under the boot of the Nazis, or the Free French under Charles De Gaulle.

Not willing to wait around for a decision that could go very badly for them, some sixty-odd Spaniards of the 6th Regiment decided to take matters into their own hands.

They stole two French Army trucks, and along with all their weaponry they made a break for British-controlled Palestine.

They met resistance from a military policeman who barred their way on the border, but that was quickly resolved with a punch to the face from one of the Spaniards.

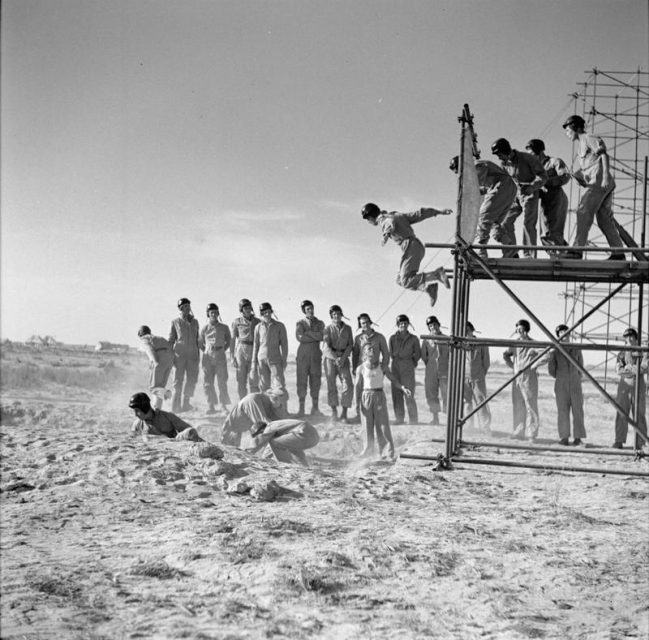

Shortly after, they found themselves being greeted wholeheartedly by Colonel George Young of the Royal Engineers. Young had recently been tasked with creating a Middle Eastern-based commando regiment, and these experienced guerrilla fighters were perfect for his needs.

Along with Jeronimo, Balerdi also found himself attached to the commandos and soon became a Corporal. An enlightened Colonel Young allowed the Spaniards to elect their own non-commissioned officers, and they were soon ready take the fight to the enemy.

At first, things did not go so well for the men of 50 Middle East Commando, as their unit was christened. They had to deal with canceled mission after canceled mission. They would find themselves en-route to a target, and the abort signal would come across the radio yet again.

During one of those aborted raids, some wise guy scribbled the words “never in the field of human conflict have so many been buggered about by so few” on a bulkhead in HMS Glengyle, the 10,000-tonne Royal Navy landing ship they were traveling in.

In February 1941 the British Army decided to amalgamate the Middle Eastern Commando with four other commando units under the legendary elite forces commander, Colonel Robert Laycock. They were to be known as Layforce and would see much action.

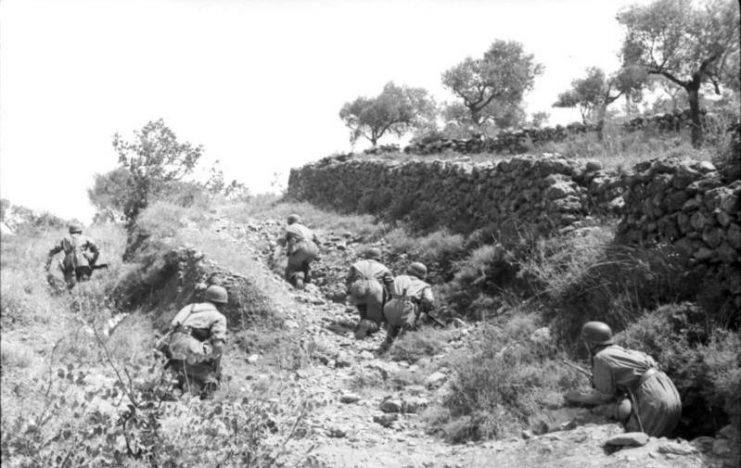

The Spaniards–now serving with E Company, D Battalion, Layforce–were chiefly involved in the bloody and heroic defence of Crete.

With the Battle of Crete raging, Layforce was thrown into the fray in an effort to retake the vital Malame Airfield from elite German Mountain troops.

However, by the time they finally landed on the night of 26/27 May 1941, they found that they were to act as a desperate rear guard, for the island was being evacuated.

D Battalion would be a blocking force that held the enemy back, fending off German paratroopers and Stuka dive bombers from one shore of the island to the other, buying time for the British and Commonwealth forces to evacuate.

By the end of the May the evacuation was over, but the majority of the surviving Spaniards now found themselves behind wire fences, as “guests” of the German army, and deeply worried about their status as Spanish nationals in British service.

Fortunately, a medical officer from New Zealand solved the issue. Captain Archie Cochrane came up with the notion that the commandos should destroy anything that would give them away as Spaniards, and tell the Germans that they hailed from Gibraltar. Since that was British sovereign territory, that would make them all British, yet could account for their looks and their accents.

The ruse worked. Those men who survived owed their lives to Cochrane, for his inspiration is the reason they avoided transportation to Mauthausen and almost certain death.

Jeronimo, however, didn’t stay a prisoner for long. He escaped quickly enough to never have been recorded as a POW by the Germans. He spent the next eleven months hiding in the White Mountains of Crete, picking up the language and passing himself off to any Germans as a Cretan.

He reportedly spent time with escaped British officers, looking after them by foraging for food and keeping them safe from discovery. When asked by one whether he wished to become that officer’s batman, or military servant, Jeronimo told him in no uncertain terms that “he polished the boots of no man.”

The eleven months passed slowly and food was scarce. Sometimes all they lived on was snails and dried grapes.

Once, Jeronimo was almost captured in a Cretan village while resting. The family shouted a warning as the Germans approached, and Jeronimo, though half asleep, reacted instinctively and made a run for the open window.

However, he mistimed his jump. His head collided with the frame and he fell to earth outside, a crumpled unconscious heap. Luckily for the family–not to mention Jeronimo–he was never discovered, even in his slumber. He woke up after the Germans had gone.

In the spring of 1942 Jeronimo was rescued from Crete in a British Special Operations Executive (SOE) mission. Plagued by malaria, he was hospitalized and nursed back to health.

At this time, he volunteered for the SAS. In Phillipeville, Algeria, Jeronimo met up with Justo Balerdi and they were reunited with Raphael Ramos. Another Spaniard, Juan Torrent Abadia, also joined them. All four volunteered for special service, and were shortly “badged” into 2nd SAS.

That meant they had to drink a toast in a Phillipeville bar and have their names changed to English-sounding ones. In part the reason was practical: few could pronounced their Spanish names. In part this was for security reasons, for they could expect little mercy if captured and identified as Spaniards.

After much laughter and drinking, one officer complained that it was all getting a bit silly. Three of the Spaniards wanted to be named after iconic British war heroes: Walter Raleigh, Francis Drake, and Robert the Bruce.

In the end, one was named after film star John Coleman, one was named Robert Bruce, and one the plain-sounding Frank Williams. The young and fiery Ramos, however, stubbornly refused to be completely renamed.

All four would see action over the next two years with the SAS, jumping into France after D-Day and harassing the enemy behind the lines during operations such as Dunhill and True Form.

Most of them made at least 3 combat jumps, and were able to wear their wings proudly on their chest after doing so. In late 1944, Jeronimo (now Williams), Balerdi (now Bruce), and Ramos would deploy to Italy, under the leadership of legendary SAS commander Major Roy Farran.

In March 1945 the three Spaniards parachuted behind enemy lines as part of a forty-strong SAS squadron tasked to join up with a ragtag band of Italian partisans. Under the leadership of Farran, they spent the next two months harassing the Germans lines of communication.

Their mission, codenamed Operation Tombola, culminated in one of the most audacious SAS operations of the entire war: the assault on the German 14th Army Headquarters (HQ), which commanded 100,000 troops holding back the Allied advance.

On that daring raid the Spaniards would distinguish themselves, and Ramos would earn the Military Medal. Captain Michael Lees of the SOE had stormed a spiral staircase at one of the HQ villas, getting shot five times in the process. Ramos carried the badly wounded Lees for many miles to safety, and thus saved his life.

“Churchill’s Spaniards” had helped make this one of the most successful operations in SAS history. But the Spaniards’ successes would come at a cost in the end.

Balerdi would come to a bloody end in his second war. On the SAS’s final assault on a German convoy in a small Italian town, driving through in jeeps with all guns blazing, Balerdi took a stray round to the head and was killed instantly.

After eight years of fighting, his war was over. Jeronimo had forged a close bond with Balerdi, and had now lost his closest friend just weeks before the end of the war.

At the end of World War II, Churchill’s Spaniards were dealt a cruel hand. After so much fighting, they reaped none of the rewards. Their country remained fascist after the war.

The Allies opted to keep Spain as an anti-communist bulwark rather than free it from Franco’s tyranny. The part these brave men had played in the war was, conveniently, largely forgotten or ignored.

Damien Lewis’ new book, SAS Italian Job, features more about this story and you can order it here!