When World War Two started in 1939, the British Army was significantly behind their German counterparts. Their tactics and especially their armament and equipment were no match to those of the Germans.

Only an occasional explosion would arouse the suspicion of locals, who started to call it their village the Bang Village.

The way things stood at the beginning of the war, the British were not expecting anything positive. This was made perfectly clear to them in the 1940 French Campaign.

When Winston Churchill was appointed Prime Minister, he was one of the few politicians in the United Kingdom who fully realized the situation. As he saw it, the British had to concentrate their efforts on sabotaging the enemy’s military and economic capacities.

For this task, small groups of well-organized men equipped with proper arms could be as effective as hundreds of soldiers. The British just had to rely on their traditional inventiveness.

It was for this reason that he was amazed by the group of inventors and scientists in the War Office department known as the Military Intelligence Research (MIR). He believed that what they did was the proper way to fight Germans.

He took control of their work, gave them a free hand, and opened up resources for them to work on some of the most interesting weapons of World War Two. They became “Churchill’s Toyshop.”

Irregular warfare department

MIR was a department founded in 1939 by Major Joe Holland, a renowned expert in irregular warfare. The task of those within MIR was to research various methods of irregular warfare.

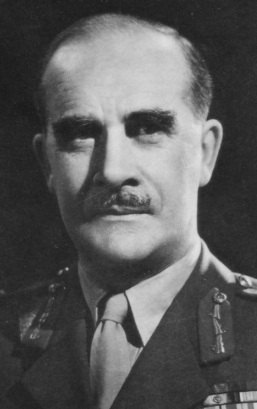

Major Holland knew that special operations required special weapons and equipment, so he established a sub-division for developing such weapons: MIR(c). In charge of this sub-division was Major Millis Jefferis from the Royal Engineers.

https://youtu.be/XRDqImtzxqk

During Major Jefferis’s pre-war military experience, he had become an expert in explosives. When the war started, he was engaged in destroying bridges and railway communications in Norway. As soon as he was appointed in charge of MIR(c), Jefferis started gathering a team of inventors

His first teammate was Stuart Macrae, an inventor and editor of the famous popular science journal Armchair Science. Macrae had some military experience working as a trainee engineer during the First World War. When he was approached by Jefferis, Macrae left his position and joined the division.

Mining the Rhine

The first project for Jefferis and Macrae was Operation Royal Marine. They designed a special mine called a “W bomb.” These mines were supposed to be dropped into the Rhine where they would float downriver to destroy German bridges and transport vessels.

Unfortunately, the operation was not successful — not because the weapon was in any way flawed, but because the operation started only when the Germans attacked France. However, around 1,700 W bombs dropped in the first week did stop German traffic on the river for a few days.

Operation Royal Marine did have a greater effect in the long run since it was a brainchild of the First Lord of Admiralty, Winston Churchill. It brought him in contact with these talented inventors, and he was more than impressed.

Under the wing of Prime Minister

In November 1940, all MIR divisions were moved to the newly formed Special Operations Executive (SOE). All, that is, except for Jefferis and his MIR(c). They became a department of the Ministry of Defense (MD1), under the direct supervision of the Prime Minister who was the Minister of Defence.

As Churchill had already seen great potential in their work, he decided to include it in his effort to win the war.

Jefferis was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and Macrae to Major. Churchill made sure that they had all the money and resources they needed through his position as First Lord of Treasury. Jefferis and his team had a free hand to do whatever they wanted and were responsible to Churchill only.

Such privileges allowed Jefferis to gather a number of great scientists and inventors in his department. However, these privileges also resulted in animosity from high officials who didn’t approve of not having any insight into the inventors’ work. All they saw was a department that was spending a lot of money on no one knew what.

It was because of such jealousy that the department got the nickname of “Churchill’s Toyshop.” The reason for this was that the entire work of the MD1 was covered by the veil of greatest secrecy and only a few people knew of their business.

Bang Village

When the war began, MD1’s residence was in 35 Portland Place, downtown London. When the first bombs fell on the city, Jefferis and his colleagues had to move their workshop to a quieter place. The village of Whitchurch in the county of Buckinghamshire was the perfect spot. It was far enough from curious eyes and at the same time close to Prime Minister’s country house, Chequers.

A large country mansion called The Firs was chosen to house the team and their workshop. It was in this isolated and large house that most of the Toyshop weapons were made. No one knew what was going on behind the fence of the estate. Only an occasional explosion would arouse the suspicion of locals, who started to call it their village the Bang Village.

The only “outsider” that was allowed to visit the mansion was Churchill. He used every opportunity to visit his Toyshop to check for new toys.

A bowl of porridge and a condom full of aniseed balls

Someone might find it hard to believe that men from the MD1 were working on top-secret government projects. They had no high-tech laboratories and were buying most of their materials in local workshops and hardware stores.

An aluminum washing bowl filled with porridge and fitted with a condom full of aniseed balls doesn’t sound like something that sinks enemy ships, but it did. These items were used to build the prototype of the famous limpet mine.

This innovative explosive device sank a number of German and Japanese ships during the war. It was made in the house workshop of Cecil Vandepeer Clarke in Bedford with only £6 being spent on parts.

To most army officials, these weapons were ridiculous and they did their best not to accept them into service. Such was the case with the sticky bomb. In the situation of a likely German invasion and given the low quantity of anti-tank rifles, there was a great need for an anti-tank weapon.

Jefferis and Macrae invented a bomb that consisted of a glass sphere filled with nitroglycerin gel and covered with a sticky compound. The bomb would be thrown and would stick to the target before exploding.

The glass sphere was put on a stick to make throwing it easier and ensure that the thrower’s hand did not get stuck to the bomb. However, a weapon that looked like a big lollipop was mocked by Army officials. They saw it as useless, even dangerous, and advised not going ahead with serial production.

In contrast, Churchill had huge confidence in inventors from the MD1. He just sent the War Office a short message: “Sticky bomb. Make one million.”

Weapons of future

At the peak of their work, MD1 employed 250 men. Their work resulted in some of the most interesting weapons of the war.

The famous PIAT anti-tank grenade launcher was developed and made in the Toyshop. The “Johnnie Walker Bomb” was an aircraft bomb that repeatedly dived underwater and back to surface until it hit the underside of a ship.

The AP Switch was a quite simple anti-personnel booby trap. It consisted of a rifle tube dug into the ground that fired a .303 inch cartridge when stepped on. The AP switch was a very nasty weapon, as the bullet would fire straight up into a soldier’s crotch. Soldiers called it the “Castrator.”

Some other weapons invented at the MD1 became an inevitable part of covert operations even after the war. Such was the case with the “Beehive charge,” a shaped charge mine designed to focus the explosion on a small area. It was perfect for blowing holes in walls and killing the enemies behind those walls.

One of the most notable inventions made in the Toyshop was the “Lead Delay Switch.” Officially designated Switch No. 9, it was a time fuse that used the mechanical creep of a lead alloy as a detonator.

Such detonators became a standard for explosive charges for a long time after the Second World War.

After the war ended and Churchill lost the office of Prime Minister, MD1 was disbanded. It was probably an act of revenge by those high officials who opposed their work from the beginning.

Read another story from us: How Churchill Became The World’s Greatest Wartime Leader

Jefferis, Macrae, and Clarke went on with their business and continued to work on new inventions. Their work at Churchill’s Toyshop had provided a solid grounding for the development of a whole new arsenal of weapons for special operations and irregular warfare.