An old proverb dictates that, “revenge is a dish best served cold,” but to Southerner Jack Hinson, revenge tasted best when he was consumed with the heat of anger and it smelled of blood. Hinson tried to live as a peaceful man, no mean trick when surrounded by America’s Civil War, as he was.

But in spite of the battles raging all around him, Hinson started no fights with his neighbors, nor arguments around the dinner table with his family. He simply would not choose a side in that most dreadful American conflict, even though he lived smack in its midst, in Tennessee.

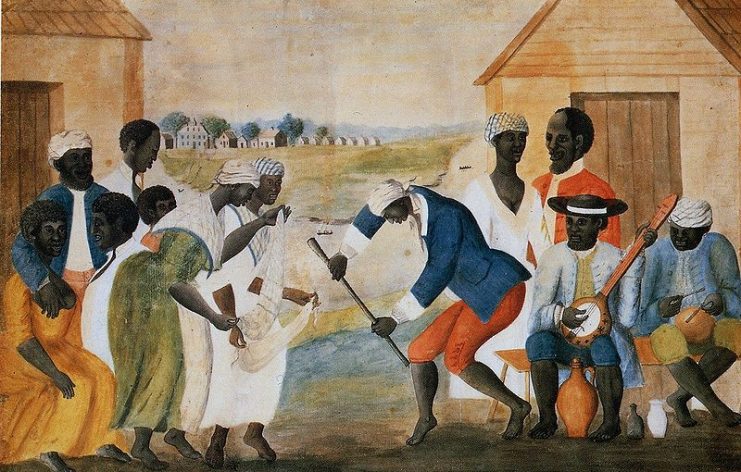

In the early 1860s, Jack Hinson lived with his wife and 10 kids on a plantation called “Bubbling Springs”. He was content to stay out of local squabbles about the war, and though he owned slaves, he quietly told his family that secession would be bad for their farming business. Still, he kept those views private, and just got on with life and taking care of his family.

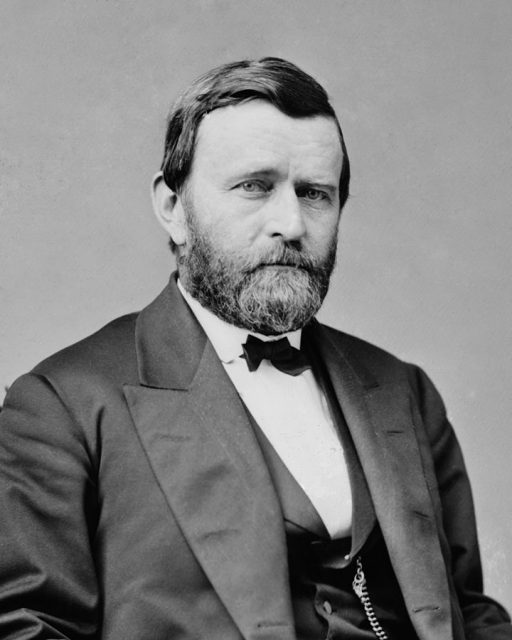

Hinson even managed to stay apolitical when he hosted Union Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, who was so enamored with the plantation that he commandeered it for his local headquarters. After Grant won the pivotal takeover of Fort Donelson, Union soldiers were a common sight along the Kentucky-Tennessee border. And yet Hinson still took no sides.

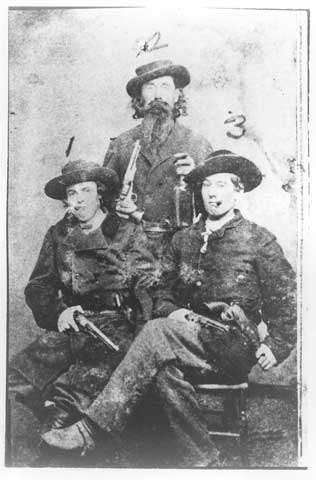

Then, events conspired to change Jack Hinson from a fence sitting farmer to a rage-filled murderer. One son signed up with the Confederacy, another with a local militia. Unfortunately for these young men, Union soldiers found them in the wilds of the region while they were deer hunting one day, and mistook them for bushwhackers.

“Bushwhackers” were men who lived in the wild, men who inflicted terrible damage on the Union troops, then melted back into the forest. They were decreed enemies of the Union, and if caught, were not given a trial, they were simply dealt with in the harshest manner possible.

Because the local structures of civility and law and justice had deteriorated so badly after the fall of Fort Donelson, some bushwhackers no longer confined themselves to killing Union soldiers. Some pillaged entire homesteads and wreaked havoc on whole communities. Consequently, they were badly mistreated before being killed by their captors.

To be mistaken for bushwhackers sealed the Hinson boys’ fate. They were murdered by a Union lieutenant, their bodies mutilated, heads severed and jammed onto the posts outside the gates of the Hinson estate. Their decapitated bodies were left rotting in the sun in the town’s central square. One was 22, the other only 17. It was only Jack’s connection to General Grant that spared him, and the rest of his family, a similar fate.

But Jack Hinson went almost mad with grief for his boys. He swore revenge, and he got it in spades. But first, he sent the remaining members of his family elsewhere so that he could exact his revenge untethered by familial responsibilities or, perhaps, his conscience.

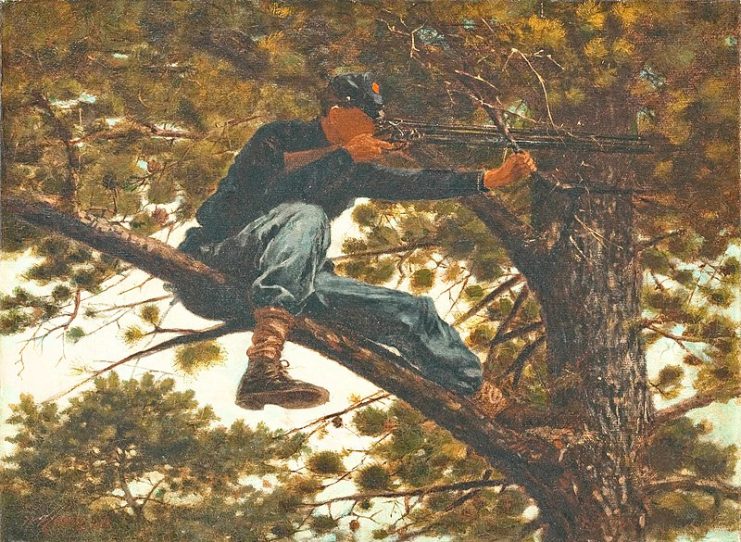

First, he needed a weapon, so he purchased a rifle made to his exact specifications, accurate to half a mile. Hinson then found a cave in which to live, taking only the bare necessities to help him survive. His first order of business was to kill the two men who were responsible for his sons’ deaths; the man who gave the order, and the one who carried it out. He killed both.

Hinson then went after Union supply boats, their captains, crews, and whatever officers he could find. He had started the war as a neutral man, he did not finish it as one. Though throughout his later life he maintained that he was on no one’s side, Union records estimate Hinson killed more than 130 officers, an extraordinary feat for a man in his late 50s when the war started.

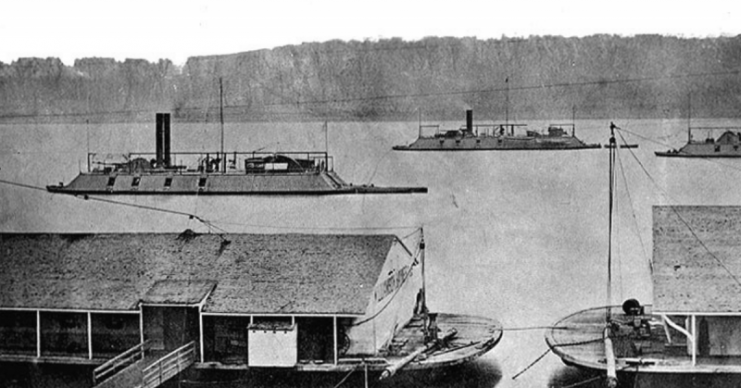

Read another story from us: Ironclads and Huge Cannons: Union Attack on Fort Donelson

Hinson finally went back to his plantation after the war. He died there, in 1874, a much diminished man, as he had lost so much of his family to war and disease. It is impossible to estimate the toll all those murders took on his soul.