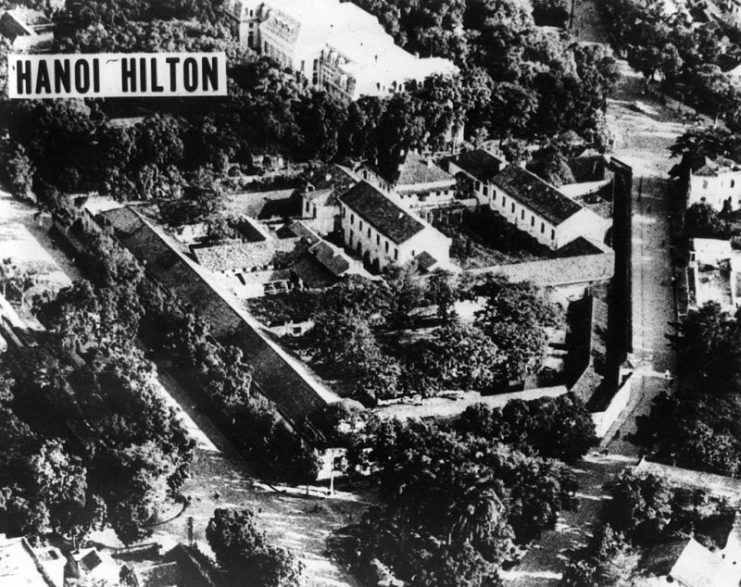

Of all the bad things that could happen to an American soldier during the Vietnam War, becoming a prisoner of war in the hands of the Viet Cong was likely one of the worst. Both Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) prison camps in the jungles of Vietnam were notoriously horrendous places, in which the general goal of the captors was to physically and psychologically break their captives down.

The means used toward this malevolent end were numerous: depriving captives of food, sleep, and water; exposing them to the elements, making them perform grueling physical labor, and, of course, torturing them. One man who the Viet Cong couldn’t break, despite everything they threw at him in their prison camp over three long years, was US Marine Colonel Donald Cook.

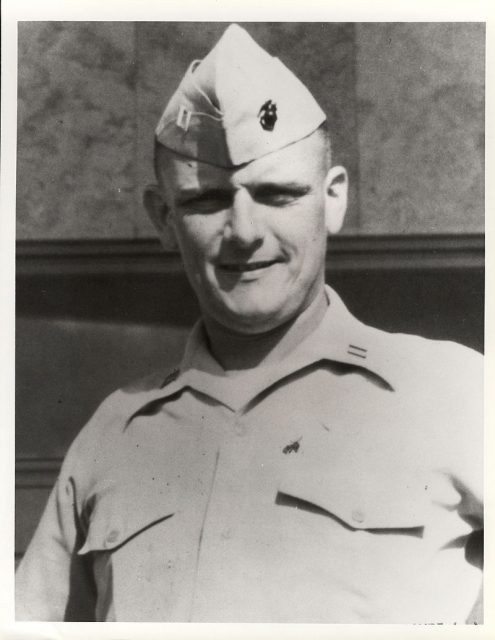

Donald Cook was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1934. The man he was to become was foreshadowed in his childhood, in which he excelled at all manner of sports, particularly football. Not simply a “jock,” though, he also did well academically.

In 1956 he enrolled in the Marine Corps as a private but was quickly earmarked as officer material. After being sent to Marine Corps Officer Candidates School, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1957.

After this, he studied and became fluent in Chinese, and attended the Army Intelligence School, where he graduated at the top of his class. After this he transferred to Hawaii, where he was attached to the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing as Officer-in-Charge of the Interrogator-Translator Team.

There he extensively researched Korean War veterans’ experiences as prisoners of war, which he used to construct as realistic a framework as possible of communist interrogation techniques. He then used what he had learned and constructed to train Marines in preparation for possible capture and interrogation at the hands of the enemy.

The tragic irony of this, of course, was that in a few short years he himself would become a prisoner at the hand of communist soldiers in Asia and be subjected to many of the exact types of interrogation and torture techniques he wrote about in Hawaii – and some that would be far worse.

In December 1964 he was reassigned to Communications Company, Headquarters Battalion, 3rd Marine Division, and shortly thereafter was transferred to Saigon, Vietnam to serve as an advisor to the Republic of Vietnam Marine Division. Not content with doing a desk job in the midst of war, Cook volunteered to lead a search and rescue party of Vietnamese Marines to locate and possibly save any survivors of an American helicopter that had been shot down.

When Cook and the Vietnamese Marines reached the wreckage of the helicopter in the jungle, they were ambushed by a vastly numerically superior Viet Cong force. While engaged in a fighting retreat, Cook was wounded in the leg and taken captive.

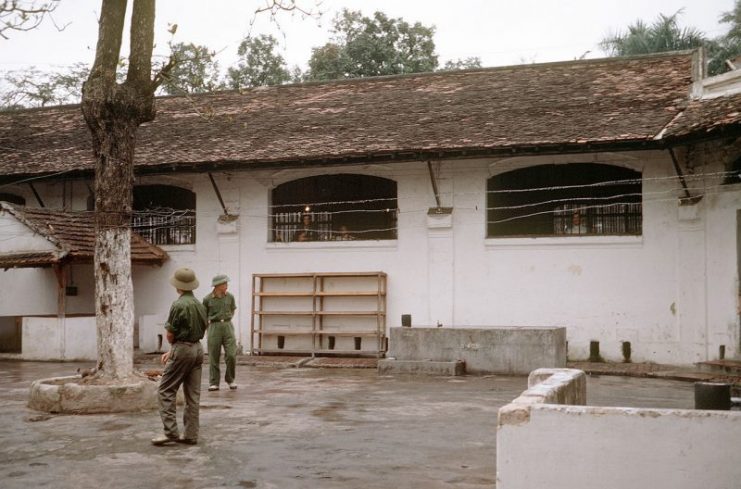

He was incarcerated at a Viet Cong prison camp in the jungle near the Cambodian border. In the camp were a number of other American prisoners of war, many of whom were in bad shape.

Cook, having faith in his own ability to endure whatever the Viet Cong could throw at him and wanting to make life easier for his fellow Americans, told his captors that he was the most senior American there, even though he was not. He knew full well that taking on this status would result in far harsher treatment for himself.

Sure enough, his Viet Cong captors immediately singled him out for “special” treatment. As part of their communist ethos, they were determined to be particularly harsh to those who came from the upper classes – like officers. Cook was subjected to solitary confinement in a bamboo cage, and was denied food, given only the barest minimum of rations to keep him alive.

Despite this, Cook was determined to resist all attempts by his captors to break him. He would run on the spot in his cage and do various calisthenics exercises to keep himself occupied and to maintain his strength.

When he was made to do grueling physical labor, he would do his utmost to outstrip the guards and not only match whatever work they were doing, but surpass them, even in his weakened state. Even when he contracted malaria and could hardly walk, he refused to let any other prisoner help him with his load.

Eventually, due to increased malnutrition and nutrient deficiencies, he started to lose his night vision and became steadily weaker. Even so, he still helped out other prisoners when he could, taking their work loads when they were sick, and using his medical knowledge to treat other prisoners who were afflicted with malaria.

He even gave up his own allowance of penicillin – vital for survival in the jungle, with its myriad diseases and means to develop infections – in order to help other sick prisoners, even though he continued to suffer from illness himself.

With his steadfast commitment to help other prisoners and always put others’ needs before his own, he managed to gain the respect of his captors. The camp commander would even compliment Cook on his grit and courage. Despite offers to negotiate his release, he refused to cooperate with his captors and divulge any information to them, and he encouraged his fellow American prisoners to be just as steadfast in their resistance.

Three years in such conditions, however, ground Cook down to a mere shell of a man. As weak as he was physically, though, he never once gave in to his captors’ demands for information. To the very end he kept on taking on other prisoners’ work and giving them his own food and penicillin rations.

He was last seen on a jungle trail in November 1967 by a fellow American prisoner, Douglas Ramsey, who was released in 1973. According to the Vietnamese government, Cook died of malaria on December 8, 1967, but his body was never repatriated, and the location of his remains is unknown.

More from us: Medal of Honor: High on Marijuana Peter Lemon Single-Handedly Fought Off Two Waves of Vietcong

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

Due to his sterling behavior in the prison camp, and continually serving as an example of what a Marine Corps officer should be even in the face of torture and deprivation, Donald Cook was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 1980.