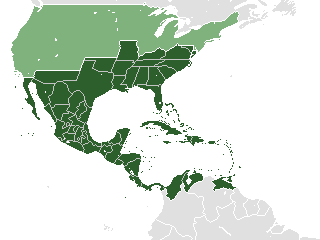

In what was a golden era for political opportunists. Filibusters seemed to thrive in the mid-19th century. The main driving aim of filibusters was imperialism, as opposed to the idea that their campaigns were for the restoration and promotion of slavery in America. Slavery was an ancillary motive of the filibuster wars but never the main objective.

They believed in the use of force to acquire new territory and took drastic measures to make it happen. The term was very commonly associated with citizens of the United States who made attempts to overtake governments in Latin America.

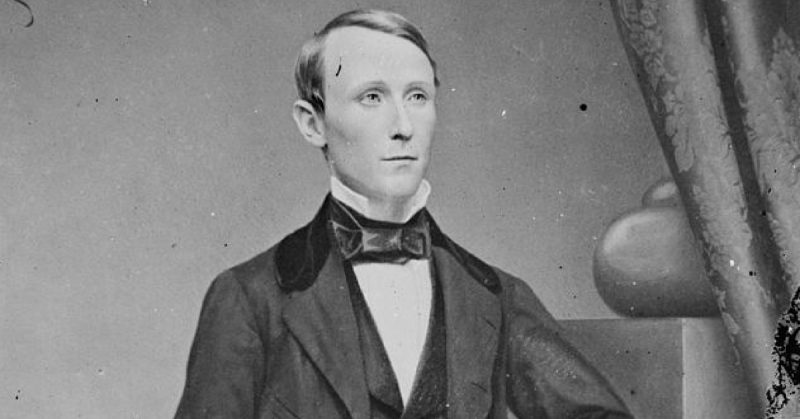

Of many such attempts, filibuster campaigns reached a climax with a remarkable maneuver by William Walker to become dictator and ruler of the state of Nicaragua.

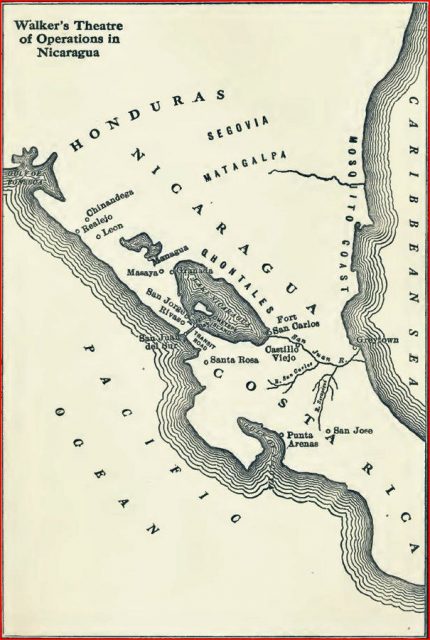

It was the year 1854 and Nicaragua was the quickest and safest trade route between New York City and San Francisco for both cargo and passengers. There were no cars or buses or aeroplanes that could get you anywhere in a matter of minutes and you ask “trains?” but at the time, the transcontinental railway system was not yet in place, neither was the Panama Canal so movement to and from those regions was through Nicaragua, making it very important for trade.

The slave trade was still a profitable business for many in the region. What happened to be a series of Civil wars in the nation ensued as a result of conflict between the Liberal party, which held its base at León, and the Conservative party with its base at Granada.

A conflict ensued between both parties after an election for the position of the Supreme Director of Nicaragua in 1853. Liberal candidate Francisco Castellón lost the election to his Conservative opponent, Fruto Chamorro.

The Liberals reported the elections to have been fraudulent and the newly elected Supreme Director soon after moved the government headquarters from Managua to the city of Granada out of fear of a coup breaking out in the region.

Members of the Liberal Party were even more outraged with the promulgation of a new constitution in the absence of any of their representatives, one which they considered to be erroneous. These actions led to war in the country, with the Liberal Party seeking a change of government.

The Liberals, in desperate need of military assistance, sought the aid of William Walker, a soldier of fortune. Walker saw the opportunity of a lifetime to fulfill his political ambitions in a warring nation that had seen no less than 15 presidents in the previous six years. He agreed to support them and brought in 45 men from San Francisco.

Upon arrival, he employed some 100 other mercenaries in what would be his fight against the Conservatives. At this time, Francisco Castellón was in command and gave the order to attack the Conservative forces in what is called the First Battle of Rivas.

The battle took place on July 29 with Walker leading the offense to the unsuspecting settlement in Rivas. His plan was to advance with his American soldiers and sweep out the enemy, where they would face an open attack with the local mercenaries following behind as backup and protection against them getting cornered for they were up against a 600 man force and were greatly outnumbered.

Walker’s soldiers wrecked a lot of havoc on the Conservatives from the opening attack. However, the natives, who were some distance away from the action, got caught off guard by a large number of soldiers and retreated under orders from Castellón, who believed that Walker and his men had been crushed.

Walker and his team of mercenaries were greatly outnumbered by the enemy, who tried to use a canon to flush out the Americans but were unsuccessful as the plan was foiled by the mercenaries. The Conservatives then managed to set one of the huts ablaze and Walker gave the order for a retreat which was carried out successfully.

Of the 45 men tightly knotted around Walker, 11 died during the war and two others were wounded whereas 70 Conservatives lay dead and 85 were wounded leaving more casualties on the side of the Conservatives than on that of William Walker.

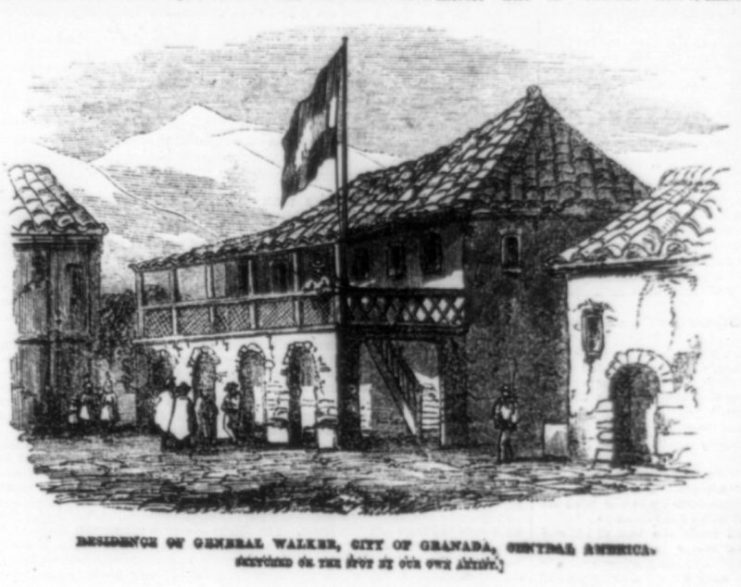

After the narrow escape from being burnt alive at Rivas, Walker and his men retreated into friendly territory and regrouped with more locals fighting for him. With his forces stronger, Walker then proceeded to launch a more offensive attack on the Conservatives and on 13 October, he defeated the defenses at the legitimist capital of Granada.

With the demise of Liberalist president Castellón in September from a case of cholera, Patricio Rivas was appointed as provisional president of the country. Walker who was now commander in chief of the armed forces of Nicaragua was in charge of the country’s decisions with Rivas merely acting as a figurehead.

William Walker exhibited extreme political ambition when he conducted farcical elections which saw the usurpation of the Rivas government and his installment as Nicaragua’s president in 1856 under the Liberal Party.

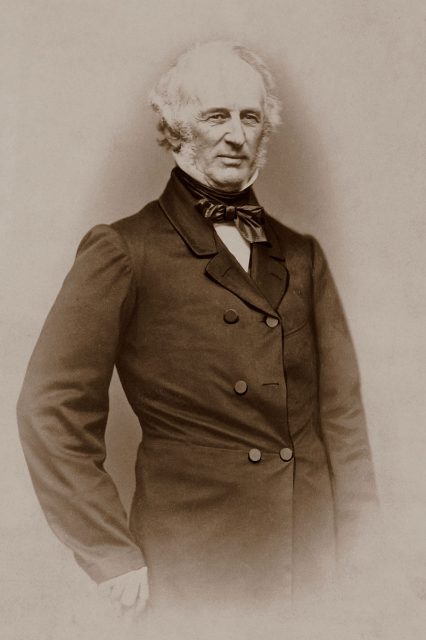

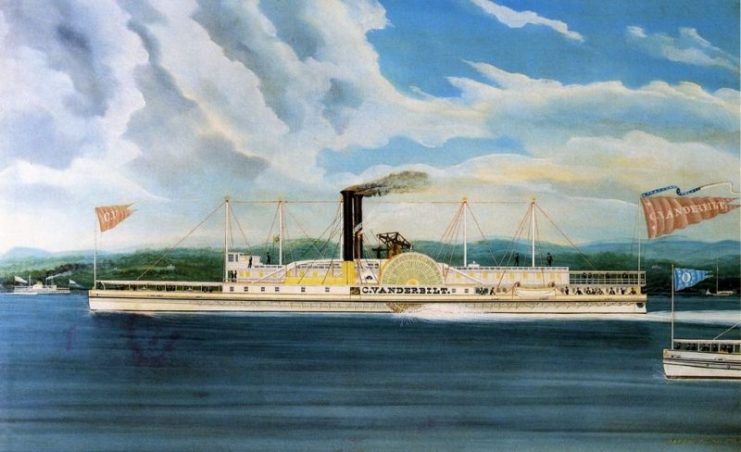

Whilst setting himself up to become president of the state of Nicaragua, Walker had stepped on some big toes and prominent among them was Cornelius Vanderbilt, a successful businessman and controller of an international shipping empire.

Walker during his campaign against the Conservatives had received $20,000 in funding from American railroad and shipping magnate Charles Morgan and Cornelius Garrison, shipbuilder and steamboat captain both of the Accessory Transit Company.

The two men had made an agreement with the filibuster to install Morgan as president of the Company upon the success of Walker’s campaign to the detriment of Vanderbilt who at the time was away on vacation in Europe with his family.

Vanderbilt discovered this plot and sent a telegram to the duo which read thus: “Gentlemen: You have undertaken to cheat me. I won’t sue you, for the law is too slow. I’ll ruin you. Yours truly, Cornelius Vanderbilt.”

Being a man of his word, Walker signed his death warrant when he revoked Vanderbilt’s Accessory Transit charter and took control of the company’s steamboats. Vanderbilt thereafter made it his life’s purpose to dethrone the ambitious American filibuster by allying himself with the Costa Rican government as well as other Central American authorities.

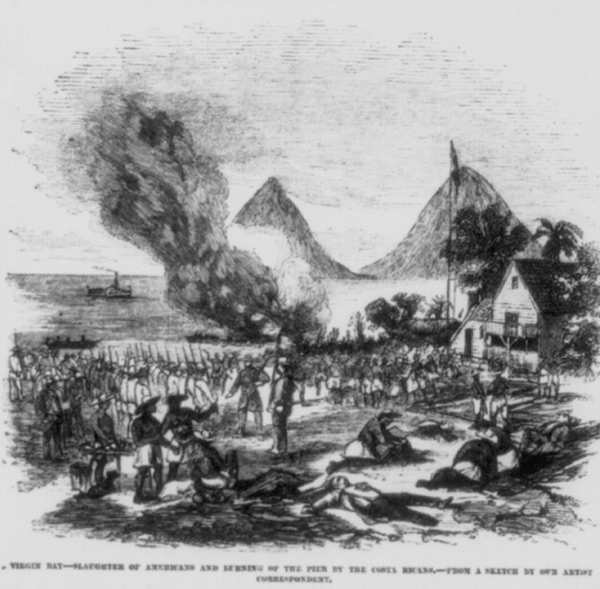

They had taken Walker’s diplomatic gestures as evidence of the man’s agenda to conquer their nations as well. This led Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora to declare war on Walker and other filibusters on March 1, 1856.

Being the richest and most powerful man in America, Vanderbilt had connections in high places and he devoted all his resources at seeing the end of Walker’s presidency including pressuring President Franklin Pierce to withdraw recognition of the filibuster as head of Nicaragua.

Walker had also stirred hatred in many hearts both from outside and from within by re-enacting slave trade in the region as well as making English the official language in Nicaragua. Several locals were angered by this decision. In April, the Costa Rica, Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras militias joined with Vanderbilt’s mercenaries and took control of Walker’s steamships cutting off his access to reinforcements.

He made his way back into Rivas but was captured in December and placed under arrest until May 1857. His release and that of his fellow officers was thereafter negotiated by a U.S. captain and Walker made his way back to New York.

After Walker was tried and acquitted of filibustering, he remained there for a while, telling tales about his escapades in Nicaragua. Many American people regarded him as a hero but the ambitious filibuster was only biding his time for a future return to the nation that held his thoughts.

He raised enough funds and ventured into the Nicaraguan state in November 1857 hardly expecting a warm welcome or a military parade. He only got as far as the Costa Rican coast before U.S. Navy officer Hiram Paulding arrested him and bundled him back to the states. He was then again tried and acquitted of all charges.

Driven by mad purpose and ambition, Walker decided to give it another go, this time taking a small army with him, he ventured into the sea and as fate would have it, their ship sailed into a reef just off the shores of Belize.

They were luckily rescued by a British warship but this did not stop the filibuster from continuing his expedition. He took his small army of 91 men and captured Trujillo, a city in Honduras. As they advanced into the country, they were met by a Honduran army and suffered heavy losses in battle reducing Walker’s army to about thirty men.

Turning around to seek reinforcements, 15 British ships cut off contact from outside the coast of Honduras. Walker and his men had nowhere to run and were subsequently captured.

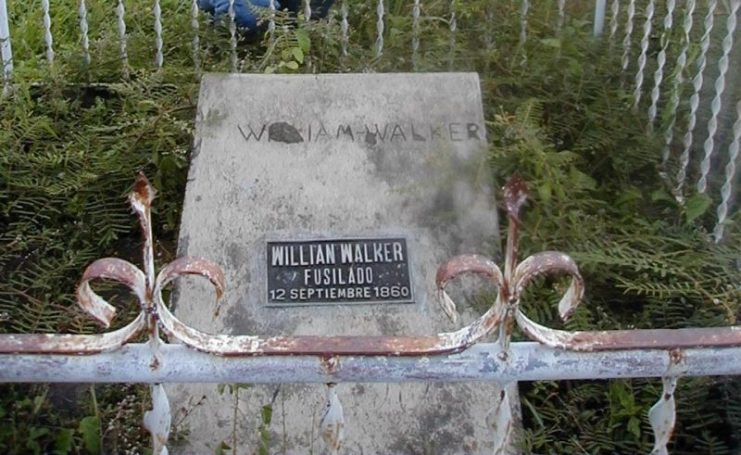

On September 12, 1860, Walker was executed by firing squad in Honduras, instilling a calm and quiet end to the trend of filibusters in Latin America.