WWI in comparison with WWII saw minimal fighting in the Far East and the Pacific. There was combat in the region, however, some of it resulting in long-lasting consequences.

Colonial Conflict

Overseas colonies were important to European powers at the beginning of the 20th century. They provided valuable economic resources, strategic bases for fleets and armies, and prestige.

The extent of each country’s holdings varied considerably. Britain had the largest empire as shown on the infamous world maps swathed in pink in British schoolrooms. The French were not as dominant but had substantial territory in southeast Asia. Germany, a relatively young country, was busy catching up. Its most important possession in the Pacific was the port of Tsingtao on the Chinese Shantung Peninsula, which it obtained in 1898. It also held the Carolines, Marianas, Marshalls, Palau, Samoa, and part of the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. Compared to the British Empire they were small fry.

At the start of WWI, Tsingtao was the home port for 4,000 soldiers and held the most powerful German navy outside Europe.

The Allied Advantage

From the outset, Tsingtao and the other German colonies were in an awkward position. Not only were the troops there outnumbered by the forces of the individual powers in the region, but most of those powers were against them. Britain had a fleet of warships based in Hong Kong. They were backed up by the fleets of Australia and New Zealand, who joined the British war effort. The French had substantial bases in Indochina.

Japan was as significant a threat locally as any of the European colonial powers. The Japanese were allied to Britain and had ambitions to carve out an empire of their own.

The Siege of Tsingtao

Seeing that Tsingtao was vulnerable, the Japanese decided to take it. They demanded the Germans evacuate. When the Germans refused, Japan declared war on them on August 23, 1914.

Japan started by blockading Tsingtao at sea. Then on September 2, Japanese troops began landing on the peninsula and laid siege to the main city.

Faced with 23,000 Japanese soldiers and 1,300 British – the Germans were outnumbered six to one. The guns of warships and artillery hammered at their defenses while troops on land forced a way forward. The Germans fought hard, and poor weather helped them, but it only delayed the inevitable.

On November 7, Tsingtao surrendered.

Picking Off the Colonies

Across the Pacific, Allied troops over ran German territory. British troops took the Solomons with little resistance. Forces from Australia and New Zealand captured Samoa in a bloodless invasion. In November, the Japanese took the Marshalls as well as Tsingtao.

By the end of 1914, almost nothing remained of the German Pacific colonies.

The East Asiatic Squadron

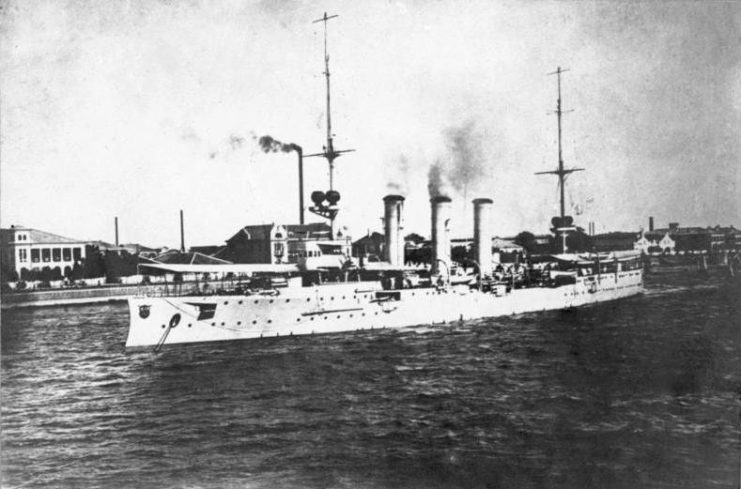

Meanwhile, the East Asiatic Squadron – seven German cruisers based in Tsingtao – were battling the Allies at sea. Their job was to cut British underwater communication cables and destroy British merchant shipping, to cripple Britain’s lines of supply and communication.

Following a few months of raiding, five of the German ships were pursued by the British to the seas off the coast of Chile. There, on November 1, 1914, at the Battle of Coronel, the Germans brought the superior range of their guns to bear, sinking two British ships and damaging a third. It was a German victory that created outrage in Britain, leading to the sacking of Admiral Prince Louis of Battenberg as head of the Royal Navy.

From Coronel, the East Asiatic Squadron rounded the tip of South America and headed into the Atlantic. They were on their way to attack Port Stanley, a British base in the Falklands, on December 8.

Unknown to the Germans, two modern battlecruisers had been sent to join the British squadron in the Falklands. They sailed from Port Stanley and smashed the German cruisers. Four of the five were sunk, and the fifth was scuttled a few months later.

The Emden

Meanwhile, of the two remaining East Asiatic Squadron ships, the Königsberg was the least successful. Its crew sank two ships off East Africa but was then trapped in the delta of the River Rufiji, damaged by enemy fire, and scuttled.

The Emden achieved the greatest success as it circled the Indian Ocean and southwest Pacific. In just over three months, it captured five British merchant ships, sank 15, and sank a Russian cruiser and a French destroyer. It also bombarded an oil facility at Madras.

Fourteen Allied ships were sent to hunt the Emden. One by one, they sank the ships providing it with supplies. Then, on November 9, the Australian cruiser Sydney caught up with the Emden at Direction Island, off western Australia. Again, guns with better range won the day, but this time they were on the Allied side. It was the first battle fought by an Australian warship and a promising start for the Australian Navy.

China

Most of the fighting in Asia was over by the end of 1914, but three years later there was an afterthought. On August 14, 1917, China declared war on Austria-Hungary and Germany, joining the war on the Allied side.

The Chinese offered to provide 300,000 troops to fight overseas. It was an offer that could not be fulfilled, due to the internal turmoil in China. Instead, 230,000 Chinese laborers were sent to work behind the Allied lines. They worked on tasks such as building railways to keep the machinery of war in motion.

A One-Sided War

The fighting in the Pacific was primarily one-sided. With no local powers to support them, the Germans were isolated. Their colonies and ships were quickly picked off by their opponents.

It was an area of the war that killed German colonial ambitions in the region while bolstering the aims of Japan. It set the stage for the subsequent world war, in which Japan sought to throw out Western influences and dominate the Pacific itself.

Source:

Ian Westwell (2008), World War I