Psychologists, historians, philosophers, politicians, poets – all have tried to understand what seems at times to be a basic human need – not food, shelter, or water, but the seemingly irresistible urge to kill each other in great numbers.

With each passing decade or less, human beings have developed newer and more effective ways of destroying each other. However, death is not necessarily a product of new technology, but of will, strength, skill in battle, and sometimes, luck.

In the long history of warfare, there have been battles that raged for days, months, or even years, like the Siege of Leningrad. These battles sometimes claimed the lives of thousands, sometimes hundreds of thousands of lives.

However, at times there have been single days of combat that have been so deadly that they have been etched on the human psyche, probably forever. Here is a short list of five of the deadliest single days in the history of warfare.

Salamis

Centuries before the developments of firearms, people were killing each other on a large scale. Many are familiar with the popular 300 films about the Greco-Persian Wars of ancient times. While historians agree that the Persians did not have a million men under arms, modern historians believe that the emperor Xerxes had somewhere between five and eight hundred thousand trained men to call upon in his empire.

After the ironically humiliating “victory” at Thermopylae, Xerxes’ rage knew no bounds and he proceeded to move forward with his operations to conquer the Greeks.

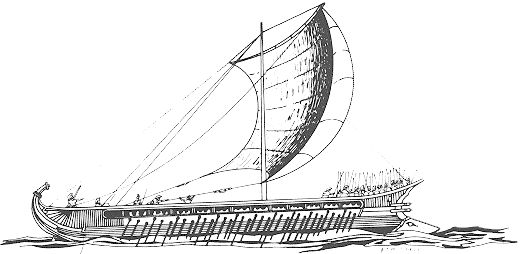

Loading his men onto some 900 galleys, he sailed them around the Attican peninsula where Athens is located, to land them on the Isthmus of Corinth. His plan was to place his army between Athens in the east and the powerful city-states of Sparta and Corinth in the west.

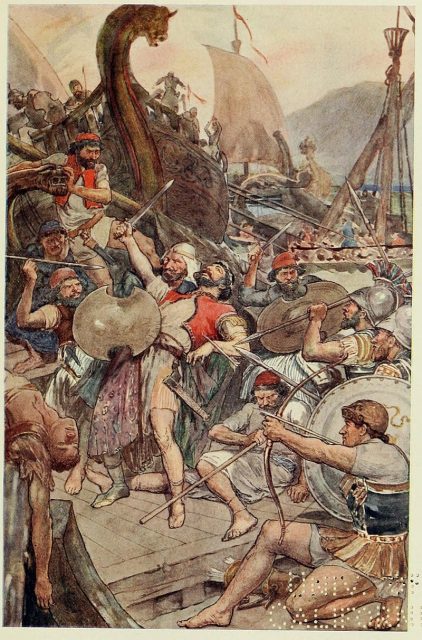

It was a good idea – in theory. However, the Persian forces pushed into the area between the mainland and the large island of Salamis, which lay just off the coast. The Greeks under Themistocles, though outnumbered three to one, hemmed in the Persians, whose fleet was both larger and made up of larger/slower ships. Then the Greeks attacked with fury.

The more nimble and better trained Greek ships moved among the Persian fleet, ramming and sinking many. Other ships were boarded and their crews slaughtered.

Not many today know this, but a notable number of Persian vessels were actually manned and commanded by Greeks, mostly from Asia Minor, which had already been subdued by the Persians.

One of them was the infamous Artemisia, the great female leader, who sank a large number of Greek ships herself. She had warned Xerxes not to sail into the area – he later told her he wished he had listened.

In this age of ramming ships, and hand to hand combat with sword and shield, an estimated three hundred Persian ships went to the bottom. Some put the estimates of dead at close to 40,000!

Cannae

For centuries after it occurred, the citizens of Rome remembered the Battle of Cannae. This battle, which occurred in 216 BC, cost the lives of almost all of the Romans involved – nearly 90,000.

Think of the butchery involved. 90,000 men on one day. Screams, smells, and sights of horror that only a relative speck of the human population has ever witnessed, thankfully.

This amazing death toll was the doing of one man, the great Carthaginian general Hannibal. For centuries afterward, Romans scared their children into sleep or obedience with the thought of him: “Go to bed, or Hannibal will get you.”

The wars between Rome and the North African city-state of Carthage were so brutal that at the end of the long series of conflicts, three wars which spanned nearly one hundred twenty years, the victorious Romans completely demolished the city of Carthage. They even sowed the earth around it with salt, so that nothing would grow there and no one would be tempted to rebuild.

Hannibal’s father, Hamilcar, had fought the Romans in the First Punic War which ended in 241 BC. That conflict between Rome and Carthage was fought for control of the Western Mediterranean and the trade which took place there. In 218 BC, after twenty-three years of “peace,” the Romans and Carthaginians went at it again.

The Second Punic War was a world war in many ways: it involved Rome and its allies, including Greeks and North Africans, against the Carthaginians, who had other allies among the Greeks and Africans. One of the main reasons for the conflict was over control of the Iberian Peninsula, or modern Spain and Portugal, just as the first had been.

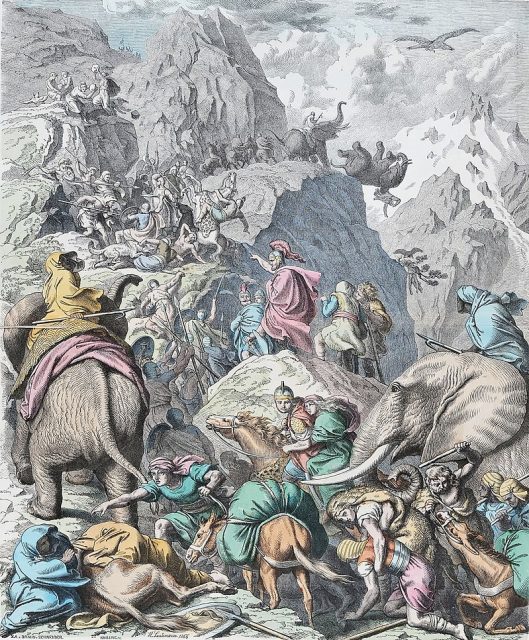

Surprising the Romans and inflicting defeat after defeat upon them, Hannibal moved into the Italian peninsula, where he remained for fifteen years.

Though he occupied much of southern Italy for this period, he was never able to completely subdue Rome. His victories, though costly to the Romans, were costly to him as well, and the source of most of his men, money, and supplies was across the Mediterranean.

However, he got very close to defeating Rome, and the closest he came was at Cannae. It is located just to the south of the “bone spur” of the Italian boot, above the “heel” and about ten miles from the Adriatic coast.

Despite an advantage in numbers, the Roman general was vastly outmatched. The Carthaginian troops were much faster than the Roman heavy infantry they faced.

Maneuvering his men faster than the ability of the Romans to react, Hannibal is said to have killed 50,000 Romans and perhaps 40,000 of their allies on the field that day. It is thought that this was about twenty percent of the trained men in the Roman army at the time.

Unfortunately for Hannibal, sometimes victories are just as costly in the long run as defeat. The Romans, faced with defeat and possible annihilation, dug in their heels and continued the fight. The war went on for years, but ultimately, Hannibal was defeated. He was then chased throughout the Mediterranean world before taking his own life circa 181 BC.

Borodino

Moving forward in time, we come to the deadliest one day battle in Russian history. Though battles in World War I, the Russian Civil War, and World War II were costlier overall, the most deadly raged for days, weeks, and months. In the case of Leningrad in WWII, they went on for years.

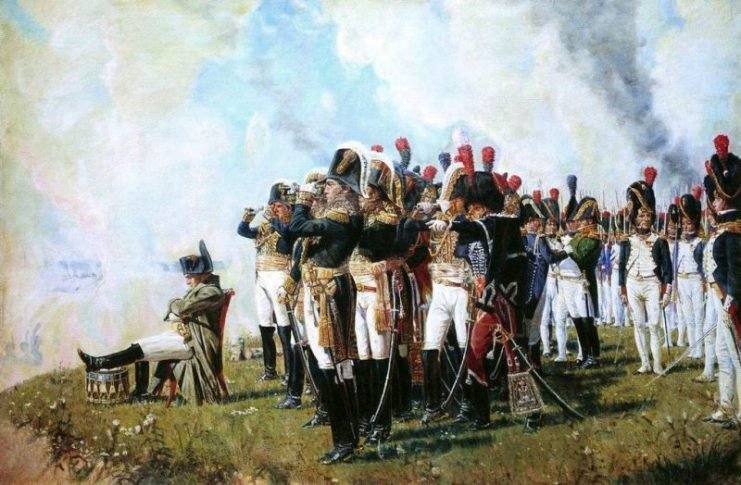

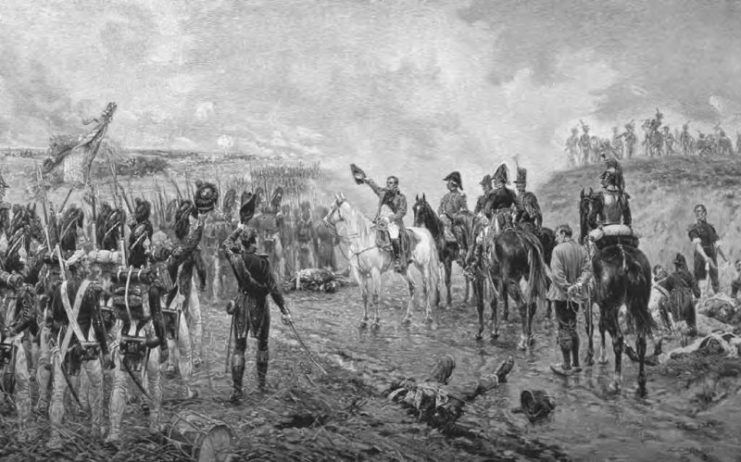

However, when Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812, perhaps the costliest one day battle in history occurred at Borodino, just eighty miles west of the Russian capital of Moscow.

Napoleon invaded Russia on June 24, 1812. Three months later, the Emperor was knocking at the gates of the capital, and Russia’s army went into the field with great desperation and bravery.

Beginning at dawn, two massive groups of men, each numbering well over one hundred thousand men, killed each other in great numbers until the sun went down.

Napoleon was the “victor” at Borodino, yet it sowed the seeds of his eventual defeat. Losing almost forty thousand men killed and wounded, many of whom would succumb to their wounds or freeze to death shortly, the French army moved into Moscow but found much of it had been purposely burned to the groun.

Lacking food, adequate shelter, and fuel, “le Grande Armee” was forced to begin its retreat from Moscow just weeks later. History records the tragedy that followed.

The Russians lost over forty-five thousand dead and wounded on that one day, but as happened in WWII, they could numerically absorb the losses, whereas the French could not. The Russians, joined by the Prussians and the Austrians, then chased Napoleon back to France, eventually forcing him to relinquish his crown and go into exile.

Waterloo

Napoleon’s life was characterized by great audacity at great odds, so in a way, it did not come as a total shock when he escaped exile on the island of Elba and returned to France in 1815 to lead it to war once again.

At Waterloo in present-day Belgium, Napoleon’s reconstituted army faced the Grand Coalition of Great Britain, Russia, Austria, and Prussia. Despite the odds, the brilliant French general almost carried the day, but at sundown on June 18, 1815, he was forced to acknowledge his final defeat.

The cost in lives was astounding: nearly 25,000 Frenchmen, 15,000 British and their European allies among the German states, and 7,000 Prussians.

The bodies lay out in the open for days. Corpse hunters and army units knocked teeth out of skulls in such quantities to sell to dentists that for years to come, people with dentures were said to have “Waterloo Teeth” in their heads.

The Somme

Of course, no list this grim would be complete without an example from World War I. The Battle of the Somme, which began on July 1, 1916, claimed nearly a million killed, wounded and missing by the time it was over in mid-November.

In a war marked by unbelievable carnage and slaughter for just a couple hundred miles of front in the west, the Somme came to symbolize the utter futility of the conflict.

It ended after great slaughter, and it began just that way. Think of this for a moment: in the Vietnam War, which essentially lasted for about ten years for the United States, the American death toll was just over 55,000 men.

In the first mere hours of the Somme, which took place in an area the size of a small city, some 20,000 British soldiers lost their lives.

The men went “over the top” and died before they could even advance a few yards. German machine gun fire simply cut them down like wheat being scythed. At a time when men from localities signed up and served together, the young male population of entire villages was wiped out in minutes.