11 Victoria Crosses and Four Distinguished Conduct Medals were awarded in this most epic of battles.

Eleven Victoria Crosses, the highest and most prestigious medal in the British military, were awarded to the defenders of Rorke’s Drift during the Anglo-Zulu War in 1879. Seven of the decorated soldiers were from the 2nd and 24th Foot, and this constituted the most Victoria Crosses ever conferred for a single action carried out by one regiment.

Zulu, the 1964 movie starring Michael Caine, is a cinematic depiction of the battle. It shows how a garrison of slightly over 100 men, including the sick and wounded, fought off 4,000 Zulu warriors in a heroic defense.

Some military historians even go as far as claiming that it was the single most courageous battle in British history, despite the relative insignificance in relation to the outcome of the Anglo-Zulu War.

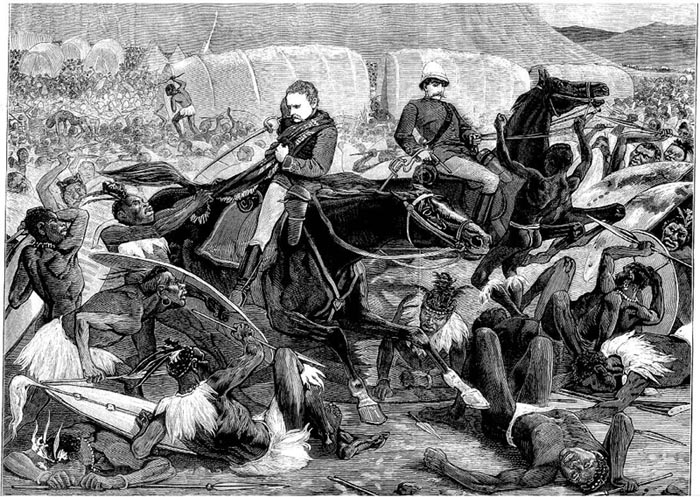

The British defeat at the Battle of Isandlwana preceded Rorke’s Drift

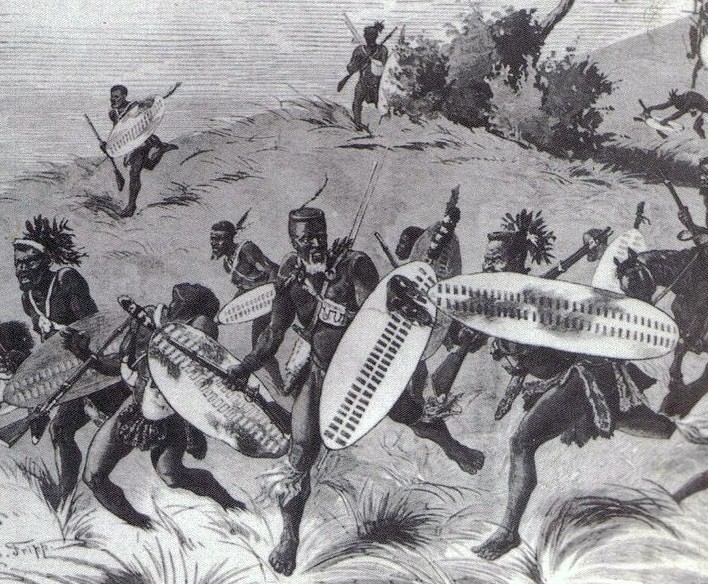

It is amazing how two such conflicting events could take place in the space of 24 hours. This was the first time in history that an army equipped with spears and shields defeated a technologically superior force and then immediately went on to be defeated in a triumph of the few against the many.

On January 22, 1879, British soldiers were camped at Isandlwana in present-day KwaZulu Natal Province of the Republic of South Africa, deep inside Zululand. These soldiers of the Empire were secure in their belief of superiority.

They were armed with the latest breech-loading Martini-Henry rifle. It was a combination of this weapon and their bravery which allowed them to hold out for over an hour until they were finally overwhelmed by the Zulus. Over 1,300 British and native contingent troops were slaughtered that day.

However, this Zulu victory came at a cost: approximately 2,000 Zulu warriors were killed and many more wounded.

Nevertheless, the Zulus, flushed with victory, were relentless. They soon turned their attention to Rorke’s Drift.

The Zulu king hoped that the politicians in Great Britain would abstain from their continued imperial land grab as a result of his victory — even though the invasion of Zululand was unsanctioned by parliamentarians in Britain.

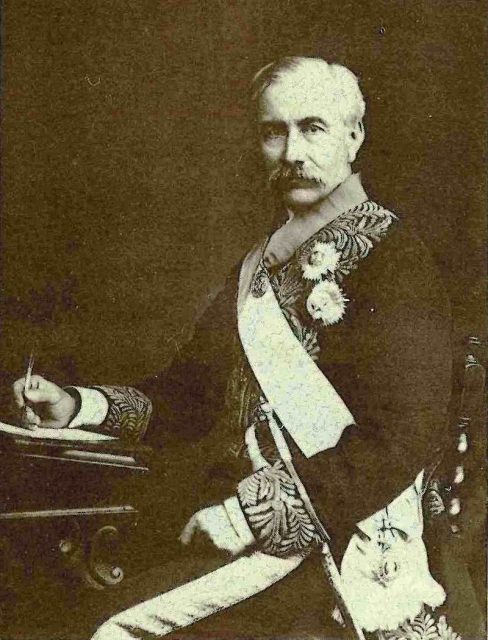

Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere, 1st Baronet, High Commissioner of Southern Africa, took it upon himself to present an unacceptable ultimatum to King Cetshwayo which included the disbandment of his “Impis” (army). A conflict was inevitable.

One side was modern, the other following martial traditions of old — but all had hearts of steel

Rank upon rank of intrepid Zulu warriors lined the hill above the mission station of Rorke’s Drift. It must have been a fearsome sight to behold.

The British soldiers stationed there had expected to prepare defensive positions and repair pontoons over the Buffalo River; they had not anticipated fighting for their lives. Probably only the local colonial troops in the garrison had any real idea of the Zulu’s military capabilities.

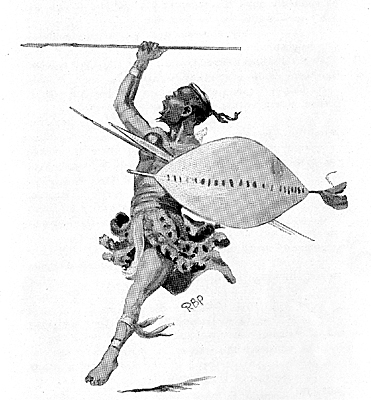

Throughout southern Africa, the Zulu warrior was renowned for his bravery, superior fighting skills, and tenaciousness. This was the case even though they were merely militia fighters.

An enemy would be unwise to allow the fact that they were only armed with spears and shields to delude him. Like the Roman legion of old, the Zulus were a resolute fighting force that, like a hacksaw, carved through enemies.

Fifty years ago, Shaka Zulu the famous or infamous (depending on your point of view) Zulu king forged a realm that exploded across the African landscape. He is credited with revolutionizing Zulu fighting tactics. For example, he introduced the short stabbing spear called the iklwa and a cowhide shield, the isihlangu.

The close-quarter tactics inspired by Shaka were simple but deadly effective. First, his troops did not walk on sandals like other tribes but barefoot. This gave them increased speed.

Second, he introduced the “impondo zenkomo” or “buffalo horns” formation. The horns were the flanking elements. The head or main body, consisting of the prime fighters, delivered the coup de grace. The loins were made up of a supporting force.

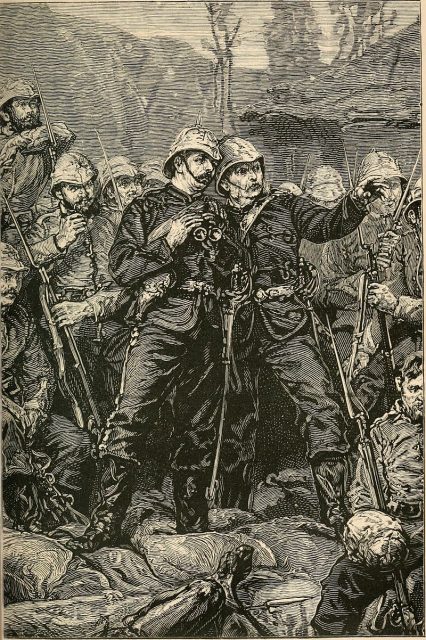

It goes without saying that the two men in command of Rorke’s Drift, Lieutenants John Chard of the Royal Engineers and Gonville Bromhead, were up against a formidable fighting force that would give them no mercy.

When Lieutenant Gert Adendorff and a trooper of the 1st and 3rd Natal Carbineers arrived as two of the few remaining survivors of Isandlwana, a decision had to be made.

The legend of Rorke’s Drift

The disconcerting news that a Zulu Impi was heading toward the mission station left ranking officer, Lieutenant John Chard, with two choices: flee with wagons containing the wounded, or stand and fight. He chose the latter of the two options.

Lieutenants John Chard and Gonville Bromhead started defensive preparations. A perimeter of mealie bags linking the storehouse, hospital, and stone kraal was supposed to hold off the enemy.

The “loins” of the Zulu army was a reserve unit consisting of men aged 30 to 40 years old. This unit appeared on the scene at 4:30 pm. The men had left camp that same morning and fast-marched across some 20 miles of hilly terrain.

The warriors’ stamina was so prodigious that they were still able to storm the British defensive position for eleven and a half hours straight without rest.

Wave upon wave of Zulus descended upon Rorke’s Drift. At first, the British were able to hold off the warriors with continuous barrages of fire. Wounded men supplied the marksmen with ammunition.

The Zulus then attacked the hospital, gaining entry and killing off the injured and the sick. However, some of the survivors managed to fend them off with bayonets.

Come nightfall, Chard and Bromhead gave the order to withdraw to the center of the mission station. The final battle lasted throughout the night. Finally, even the gallant Zulus had had enough.

The men at Rorke’s Drift waited in silence. They expected the next wave to arrive, but it never did.

At 7 am the following day, January 23, 1879, a Zulu Impi appeared on the crest of the hill. The British manned their positions, expecting to die. After a few nail-biting moments of deathly silence, the soldiers of Africa stole away like wraiths, never to appear again.

Some historians believe that had the Zulus attacked in force one last time that they would have overrun the station and won the day. But we will never know.

The British started with 24,000 rounds of ammunition. By the time the fight was over, a 600-round box and what the men had left in their munitions pouches was all that remained.

About 350 Zulus and 17 defenders lost their lives during the actual battle.

Another 500 Zulus who had been wounded in the attack were killed during the ensuing slaughter at the hands of the British relief force afterward. The British claimed it was a quid pro quo action in retaliation for the brutal treatment of the surviving British servicemen in the aftermath of Isandlwana.

The defenders of the station took no part in the culling.

Read another story from us: Napoleon & the Zulus – Death of the Little Prince

Rorke’s Drift was a welcome boost to British morale after the defeat at Isandlwana. The Anglo-Zulu War continued for several months until the valiant Zulus were finally defeated at the Battle of Ulundi, the Zulu capital.

King Cetshwayo was captured, and his kingdom became a part of the British Empire ten years later.