In May 1944, the USS England achieved a remarkable victory when it single-handedly destroyed an entire squadron of Japanese submarines.

This victory was made possible by the skill of the England’s executive officer and by the adoption of a strange weapon: a mortar called the hedgehog.

The Hedgehog

The hedgehog was the brainchild of Major Millis Jefferis, a British officer working in a secretive department in Britain’s Ministry of Supply. His job was to produce specialist armaments for use in the war against the Axis powers.

Jefferis’s department created a wide range of weapons, from limpet mines to unusual hand grenades. These often went through unexpected changes during the design process, and that was particularly true for the hedgehog.

The hedgehog was originally created as a land-based sabotage weapon to be used behind enemy lines if the Germans invaded Britain. But it ended up becoming a naval weapon employed to destroy submarines.

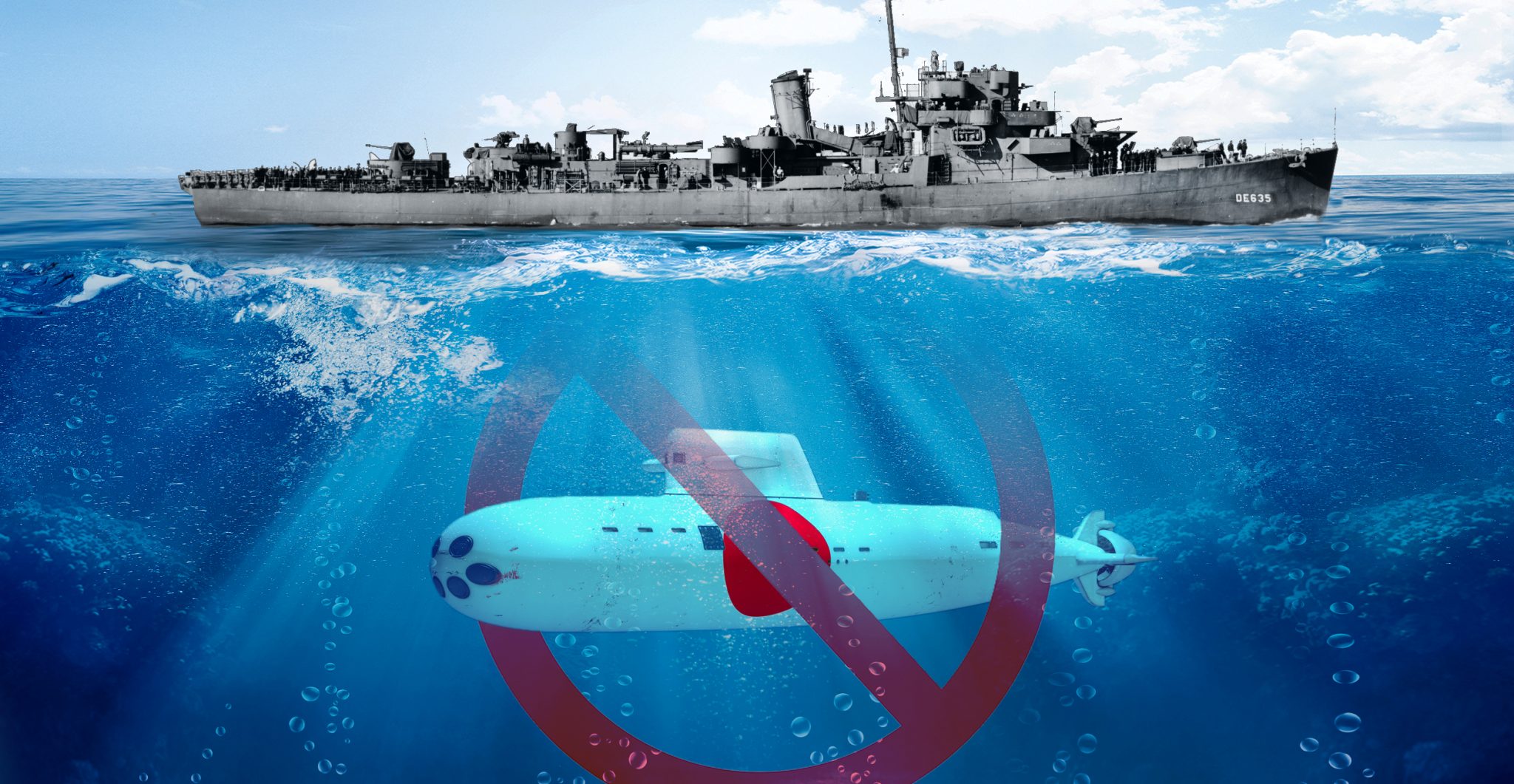

The hedgehog fired a whole cluster of explosives at once. These hurtled up into the air, then plummeted down into the water. Using carefully calculated mathematics, their arcs would cause the weapons to cluster together to ensure maximum impact as they hit a submarine.

Unlike a depth charge, a hedgehog round only exploded if it hit an enemy vessel. This ensured that the full explosive force was delivered to the enemy. It also meant that the crew would know if the weapon had hit because otherwise there would be no blast.

Adopted by America

The hedgehog was first installed on British ships in 1943. The British were heavily engaged in battling German u-boats, both to maintain the naval blockade on Germany and to protect supply convoys. But British naval commanders were wary of this new device, preferring to stick with depth charges.

The Americans proved more enthusiastic. Late in 1943, they fitted hedgehogs to a number of their ships, including the USS England, a destroyer escort. Given its name, the England was a particularly fitting transport for this English-made weapon which would soon be put to good use.

Squadron Seven

In the spring of 1944, Admiral Soemu Toyoda created the plan for Operation A-Go. This was a concerted effort by the Japanese military to destroy the US Navy in the Pacific. Supply and transport lines in the Pacific were almost entirely seaborne, so if the Japanese could take control of the waves, then they could halt Allied advances.

Toyoda knew that submarines would be crucial to the success of A-Go. Rear-Admiral Naburo Owada was given command of Squadron Seven, a submarine force with a key role in the battle.

Owada’s orders in the buildup to the operation, given to him by Toyoda on the 3rd of May, were to launch a surprise attack against Allied task forces and invasion forces, an attack which would stop Allied attempts to strike against the Japanese.

Unknown to Owada, the Americans were intercepting many of the signals about his operations. US officers learned that the I-16, one of the largest Japanese submarines, was heading toward the Solomon Islands, commanded by the brilliant Yoshitaka Takeuchi.

It was time to take the hedgehog hunting.

John Williamson Goes Hunting

Details of the I-16’s movements were sent to the England. The ship was commanded by W. D. Pendleton, who set out to hunt down the Japanese boat.

Pendleton’s executive officer was John Williamson, a smart young officer who was also a tech geek. While the England was still in San Francisco, he had carried out test firings of the hedgehog into the harbor. He was convinced of the weapon’s power.

Filled with excitement, Williamson and the rest of the England’s crew set out to hunt down the I-16. It was a dangerous mission. With the powerful Japanese ship lurking just beneath the waves, one mistake on their part could see them sunk by enemy torpedoes.

At 1:25 pm on the 18th of May, the England’s soundman, Roger Bernhardt, detected the I-16 1,400 yards (1,280 meters) away. The battle was on.

First Blood

The England’s engines turned to full power as she raced to intercept the I-16.

Takeuchi was an expert in his craft. At a range of 400 yards (365 meters), he turned hard left and kicked the screws on his sub into high gear. He was using a technique called kicking the rudder, in which a submarine captain caused as much disturbance in the water as he could. This distorted sonar echoes, making it hard for the enemy to find him.

But Williamson was also an expert. Using the data gathered by the England‘s sensors, he sat down to calculate the location and exact depth of the I-16. At 2:33 pm, Williamson got a fix on the I-16. Using the results, he targeted the hedgehog.

A moment later, the hedgehog roared. A perfect ellipse of mortar shells raced into the air, then descended into the ocean.

Williamson waited in tense silence, desperate to see if he had hit. Then there was an explosion, and another, and another, and another.

Punctured by six hits, the I-16’s hull crumpled and then collapsed. Catastrophic decompression tore the sub apart, wrenching its crew out into the ocean.

The England had its kill.

Twelve Days

For the next 12 days, the England hunted the rest of Squadron Seven through the Pacific. Thanks to Williamson’s math and the power of the hedgehog, they took out another five submarines.

On the 15th of June, Admiral Toyoda sent the order to launch Operation A-Go. To Admiral Owada, he sent orders for Squadron Seven to move immediately east of Saipan, where they would intercept American transports and carriers at any cost.

But the cost had already been paid. Owada messaged back, saying that Squadron Seven had no submarines.

The hedgehogs had destroyed them all.