Massimo “Max” Domenico Bondone is an experienced deep-sea diver and explorer from Italy. He is credited with both finding and identifying the wreck of HMS P311, a British submarine lost in 1943.

Bondone has been wreck-diving for years and has been credited in the past with some truly interesting historic finds. For example, he discovered the SS Kreta near the island of Capraia, Benghazi in Sardinia and San Marcos off Villasimius.

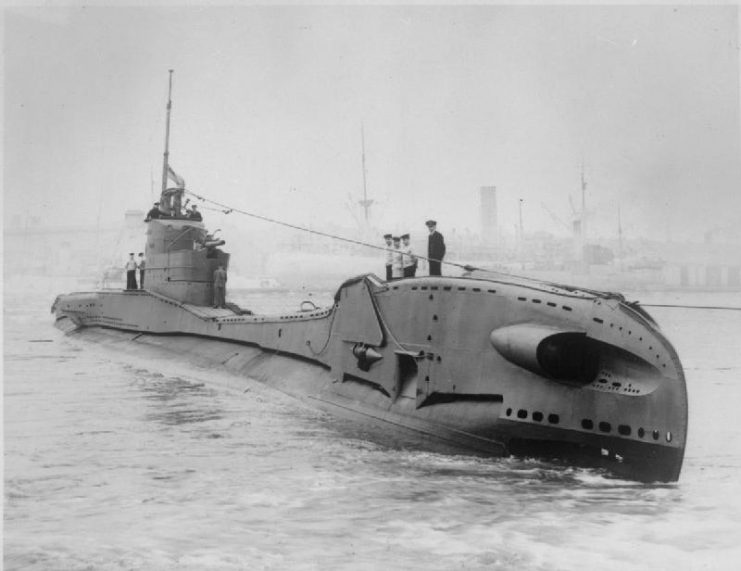

When he discovered this new wreck, Bondone was able to make a positive identification due to quite a distinctive feature: two Chariot “manned” torpedoes. These were small, two-pilot assault submarines that could move stealthily into enemy ports to place underwater charges on enemy vessels. These small submarines were still attached to the hull of P311.

At the end of December 1942, the Class T HMS P311 left Malta on its first mission. It wasn’t going to be an easy mission, some might even have called it suicidal. The ambitious goal was to reach the point of La Maddalena and hit the Italian cruisers the Trieste and Gorizia. But the P311 never made it.

In January 1943, the P311 struck a mine off of Tavolara and vanished beneath the waves. It was a stormy night, and a local fisherman claimed the collision sounded like a loud roar. No one in the decades since has been able to find the British submarine.

That is, until May 22, 2017, when Bondone discovered the wreck a few kilometers from the Gulf of Olbia. The P311, at 84 meters long and 8 meters wide, was still intact and lying on the seabed.

The only visible damage was to the bow of the vessel, damage which was caused when the mine detonated. A cannon that was positioned in front of the turret served as another hint to the submarine’s identity. However, the presence of the Chariots made the identification a certainty.

The discovery was both exceptional and important, as the P311 is generally believed to be the final resting place of her crew. Those on board numbered 61 crew members, two engineers, and the eight operators of the two Chariots.

There is a high probability that the middle compartments of the submarine were not affected by the explosion of the mine and so were not flooded. As such, the internal structure would not have been compromised and would have remained sealed since that day in January 1943.

Bondone indicated to La Nuova Sardegna that these wrecks should be treated with respect. These men worked under very difficult circumstances, including poor living conditions, tight spaces, and the constant anxiety of being hit by either a torpedo or a depth charge.

The British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, minuted the Admiralty on three specific dates – November 5th, December 19th, and December 27th – saying that all submarines serving in the Royal Navy required names.

In that final minute, he included a list of suggestions with a timeline for completion. It was clear that all submarines needed to be given names within a fortnight.

Read another story from us: HMS Churchill Sunk by U-Boats but the Bridgeplate is Preserved in Devon

The HMS P311 was a T-class submarine of the Royal Navy, and the only ship in its class never to be given an official name. If it hadn’t been sunk, the P311 would have been named Tutankhamen, after the Egyptian pharaoh.

Unfortunately, it was sunk before the title could be formally confirmed. Having lost the chance to acquire an original, official name, the submarine’s designation remained simply P311.