Every American who went to school in the 1950s or 60s will remember air raid drills, the “Duck and Cover” slogan, and talk of fallout shelters. Images of elementary school children huddled under their desks with their hands over their heads are burned into American cultural history.

However, these measures stopped being used in most schools in the 60s, and fallout shelters began being repurposed in the 70s. Why would that be the case? Would these drills have saved thousands of lives in the event of a nuclear attack, or did they merely serve to terrify young children?

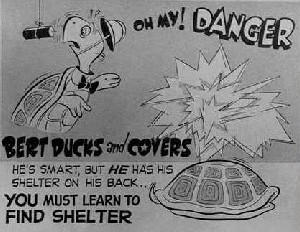

One of the most ubiquitous symbols of United States government civil defense efforts was Bert the Turtle. Bert was an anthropomorphic turtle who explained to kids, through pamphlets and television, that they should “Duck and Cover” under their desks to “avoid the things flying in the air” if nuclear bombs were to explode nearby.

This strategy may have been well and good to avoid flying glass from broken windows, but this raised a simple question: If the goal was to protect students from flying shards of glass, why not just move the students to a place no windows? After all, if the explosion were far enough away to not immediately damage the room before kids could hide under their desks, there would probably be enough time to get into the hallway.

The more informed of the populace also pointed out that if students were close enough to an explosion for windows to shatter, they were easily within range of radiation, and probably in range of a blast radius that could destroy entire buildings.

Nuclear detonations lead to significant changes in air pressure, which in turn leads to shockwaves that are powerful enough to destroy cement buildings that are close to the detonation. The meaning of “close” is of course relative to the size of the bomb.

Among the most dangerous aspects of a nuclear detonation is the resulting heat blast, which can lead to fatal burns. If buildings were being blown away, and a fireball was incinerating the area, hiding under a desk would not save anyone. Even if one was far enough away to survive, there would still be the risk of radiation and fallout, which duck and cover would do little to prevent.

On top of that, the odds were that if a bomb fell, it would be the start of a massive nuclear war in which thousands of bombs would be dropped, leading to multiple fireballs, remarkable amounts of radiation, and many shockwaves that would destroy buildings.

Obviously a desk would be a useless defense against such an attack. In response to the above points, schools and other public buildings soon began incorporating fallout shelters to address some of these concerns.

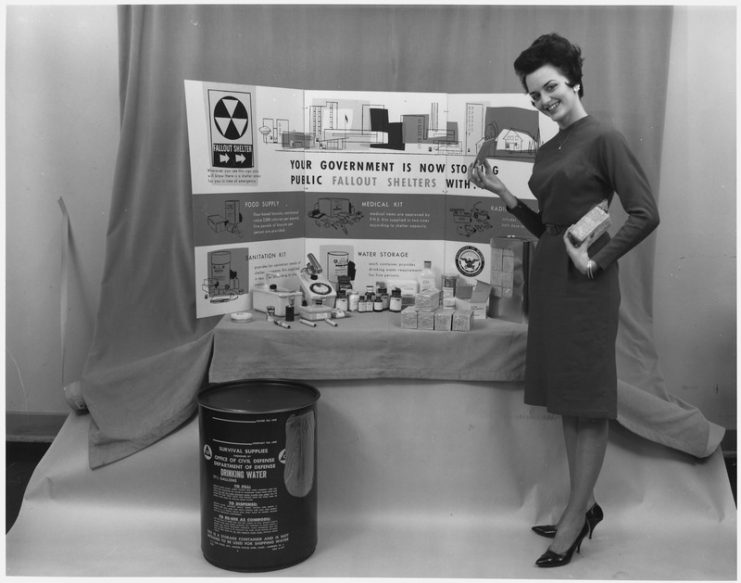

Even today, signs still indicate the presence of fallout shelters in some major cities, but would these shelters be enough to protect the modern day populations of those cities? The answer is “not even close.” Jeff Schlegelmilch, deputy director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, explains:

“They’re a relic of the Cold War. They largely just don’t exist anymore.” In many instances old fallout shelters have been converted into storage space, and the emergency supplies that were once there were removed decades ago when federal funding ran out in the 70s. Imagine sprinting to the local shelter only to run into a room full of filing cabinets!

Experts also note that nuclear fallout takes about 10-15 minutes to reach the ground, so going to existing shelters could be counterproductive if they take longer than 15 minutes to reach. Ironically, an attempt to reach the safety of the shelters could result in more people being caught outside and exposed to more fallout than if they stay inside their own homes.

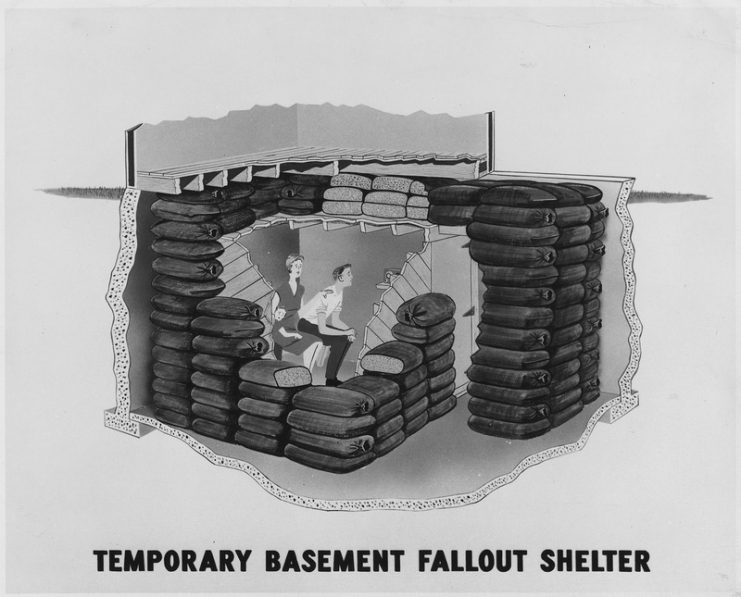

Some might think that the backyard shelters several companies sold to consumers in the 50s, 60s, and 70s are a plausible option for safety, as they could be reached in only a few minutes. Although these might have offered some protection from the weapons of the early Cold War, they were made obsolete very quickly by the increased power of rapidly advancing nuclear weapons technology. They did not have the structural integrity to withstand any nearby attacks, let alone multiple attacks.

The civilian defense measures taken during the Cold War overlooked some very fundamental aspects of a nuclear war. As the Cold War dragged on, both sides developed more sophisticated weapons. A fallout shelter could never stand up to a hydrogen bomb, for example. Shelters in the middle of major cities would likely suffer almost a direct hit and thus be completely destroyed. In fact, two-thirds of shelters were built in high risk areas that would have likely taken a direct hit from a bomb(s).

The advent of fusion bombs was the final nail in the coffin for both the duck and cover and fallout shelter ideas. Kate Kelly of the Huffington Post explains that “Ivy Mike, the code name given to the first nuclear test of a fusion device, made it clear that children huddled under coats in hallways…was not adequate against a weapon that created a crater 6,240 feet (1.9 km) wide and 164 feet (50 meters) deep.” Essentially, fallout shelters had already been rendered useless in 1955, when the Soviets made their first thermonuclear bomb. What is the point of worrying about fallout if almost everybody dies when the bomb goes off?

So why did the government bother with all of these drills and fallout shelters into the 70s, when they were clearly obsolete by the mid-50s? In fact, public fallout shelters only began being built in the 60s in major cities! The best bet is that the government was hoping to alleviate panic and avoid the perception, however accurate, that it could do little to protect citizens in the event of a nuclear attack.

Essentially, it was a way to give people hope. However, educators at the time reported that the drills ironically frequently made students, especially young students, significantly more anxious and unable to focus on their studies. Of course, adults were not entirely reassured by the constant presence of black and yellow fallout shelter signs all over their cities,

especially since it occurred to the general public that multiple bombs would be dropped and that the weapons were strong enough to destroy the shelters anyway. In 1962 Life magazine quoted a bank teller as remarking, “An attack wouldn’t be one bomb, it would be many…We’d die in those shelters.”

However, this leads to a great irony: nuclear threats today are much more diverse, and in many ways resemble the attacks that the Cold War shelters were originally designed to protect against, making them relevant once again. For example, Glenn Reynolds explains in USA Today that “the attacks we fear look more like 1950 than 1965. If the United States is nuked, it will likely be a single device from a terrorist state, probably no bigger, and possibly smaller, than the Hiroshima bomb.”

The obsolete defense measures of the 50s and 60s could possibly be used in the event of a dirty bomb attack on American soil, since a rogue state or terrorist organization would be unlikely to be able to hit a specific area with more than one small bomb. Fallout shelters not too far from the bomb would be able to survive such a blast, and even simple measures to protect from fallout might be useful.

Despite the flaws of obsolete means of preparation for nuclear attacks, some basic elements have stood the test of time. For example, the general principal of finding hard cover and avoiding any place that allows exposure to the outside environment still applies. Even though fallout shelters might not be reliable, the government still suggests that people find cement or brick buildings to take cover in, and to go underground if possible.

At the very least it is crucial to find an indoor location and avoid areas with windows. Experts also recommend stockpiling enough food, water, and first-aid to last several days. Lastly, if there is any chance that exposure to fallout could have occurred, it is best to remove outer layers of clothing and take a shower to wash off any fallout particles.

Read another story from us: The Man Who Survived Both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Atomic Bombs

These measures, however, really only stand a chance of saving anyone if they are a specific distance away from a single explosion in which they may suffer fallout, but not significant burns or a strong shockwave. Although some of these plans can be useful, they are limited to very specific circumstances.