A short while ago, a celebrated WWII hero died. This hero didn’t storm any beaches, assault a strong-point, or parachute behind enemy lines. This hero appeared unassuming, and anyone who didn’t know better couldn’t be blamed for taking this person for just your everyday… housewife.

Freddie Nanda Dekker-Oversteegen, known to most by her given first and last name, Freddie Oversteegen, did indeed look in later years like a typical Dutch housewife. Yet she and her sister were Dutch national heroes.

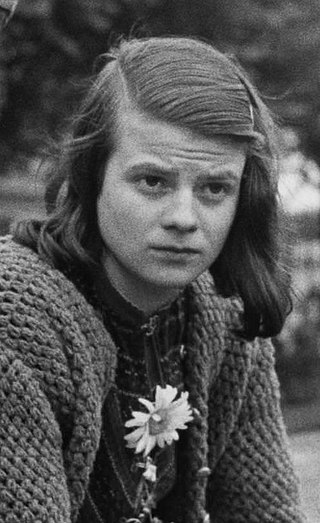

She died September 5, 2018, at the age of 92. Freddie’s sister Truus, the leader of the group, died two years ago, and the third member of their cell, Hannie Schaft, was executed by firing squad in 1945 by the Germans. All three were decorated by the Dutch government.

The Oversteegen family lived in the small village of Schoten, which was absorbed into the city of Haarlem in 1927, two years after Freddie was born. In a very typical Dutch scene, the Oversteegen family lived on a barge and were able to hide Baltic refugees after the Soviet invasion in 1940. When her mother and father split, Freddie and her sister went with their mother, an avowed communist.

The sisters, along with their mother and new step-father, were strong activists. When Holland was invaded, they hid a Jewish couple in their apartment for a time. Unfortunately, the couple were later arrested and died in a camp.

Freddie and Truus, at the ages 16 and 14 respectively, began handing out anti-Nazi pamphlets by themselves. This was exceedingly dangerous since the Nazis were not above jailing or executing teenagers. For much of the war, Holland had its fair share of collaborators who were more than willing to turn in resisters for Nazi favor.

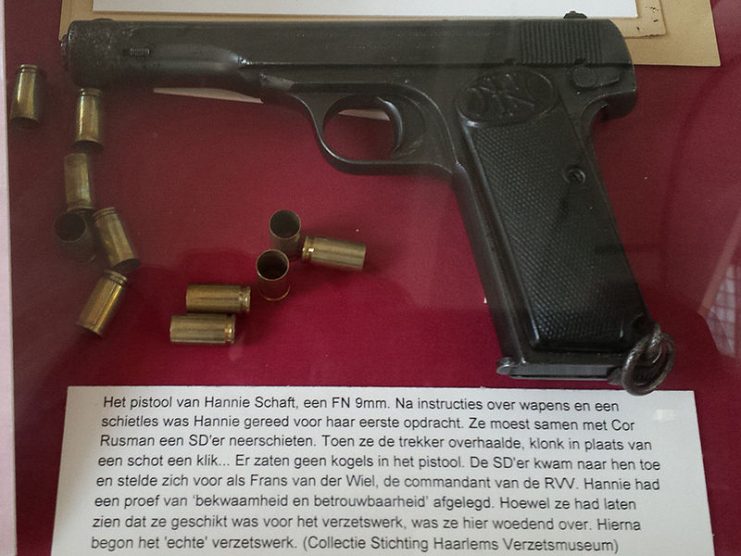

Luckily for the sisters, they came to the attention of commander Frans van der Wiel, a leader in the local “Haarlem Council of Resistance.” The girls’ mother gave her blessing to her daughters joining the resistance cell. The girls and other resistants were trained with explosives, as well as in sabotage and espionage.

At first, they thought they might be just doing “girls’ work,” but Truus has been quoted as saying “Only later did [Frans] tell us what we’d actually have to do: sabotage bridges and railway lines… We told him we’d like to do that. ‘And learn to shoot, to shoot Nazis,’ I remember my sister saying, ‘Well, that’s something I’ve never done before!'”

She and her sister formed a triad with Hannie Schaft. They were regularly sighted on the streets of Haarlem, riding their bicycles through town as if on the way to school or doing other things that teenage girls might do. However, often their bicycle baskets carried guns, maps, and other resistance paraphernalia.

The girls learned German and carried out other missions. They were living in different, desperate times and, as the saying goes: “Desperate times call for desperate measures.” The girls were not above seducing young German soldiers or even older officers. Holland might have been a more sexually permissive nation even then, but this was Holland in wartime, under very harsh German rule. Such actions were still very risky.

Sometimes the girls would ride their bikes in search of a deserted area where a German soldier might be off-guard and walking alone. In a slower version of a drive-by, the girls would pass the soldier and shoot them dead. They did this even in broad daylight.

Freddie was the first one to kill a German soldier. Passing pamphlets was one thing, killing a German soldier was another. If caught, the girls would be killed, and their young age would be no defense.

It was not until 1945 that such misfortune struck. Red-haired Hannie Schaft was caught distributing a communist newspaper. She was tortured and interrogated for days.

Just a short while before an informal truce was to begin between the resistance and collaborationist militia, Hannie was taken to a remote location by two men to be executed. The first shot only wounded her. She reportedly told the man, “I shoot better than you,” before the other man stepped in and fired the killing shot.

The sisters developed their own tactics. They would go to bars, flirt with a German soldier, and ask him if he wanted to “go for a stroll in the forest.”

Once away from prying eyes, the girls would lead the soldier out to an isolated make-out spot and shoot him. Of course, over time, they operated in areas far from home, and they couldn’t stay in one place too long without risking detection.

In later years, Freddie and Truus were reluctant to talk about killing the Germans. “It was tragic and very difficult and we cried about it afterwards,” Truus said. “We did not feel it suited us — it never suits anybody, unless they are real criminals. . . One loses everything. It poisons the beautiful things in life.”

Freddie tried not to talk about it at all, but when she did, she often said this: “Yes, I’ve shot a gun myself and I’ve seen them fall. And what is inside us at such a moment? You want to help them get up.”

Read another story from us: Rainbows and Unicorns – The Planning Flaws of Operation Market Garden

Hannie was killed just before the end of the war. For a short time, she was heralded as a national hero, and a movie was made about her life called “The Girl with the Red Hair.” But in the 1950s, communism became anathema in Holland, and tributes to Hannie were sadly ended for decades.

When Truus died in 2016, and when Freddie died just days ago, they were also heralded as national heroes – as they should be.