In 1600, two Dutch ships terrorized the Philippines. They then went on to become the fourth group of Europeans to circumnavigate the world.

This is recorded in “Events of the Philippine Islands,” published in Mexico in 1609. Praised by historians, it describes the Philippines in not only the early years of Spanish occupation but also the bravery of its Spanish vice-governor in fighting off the Dutch… sort of.

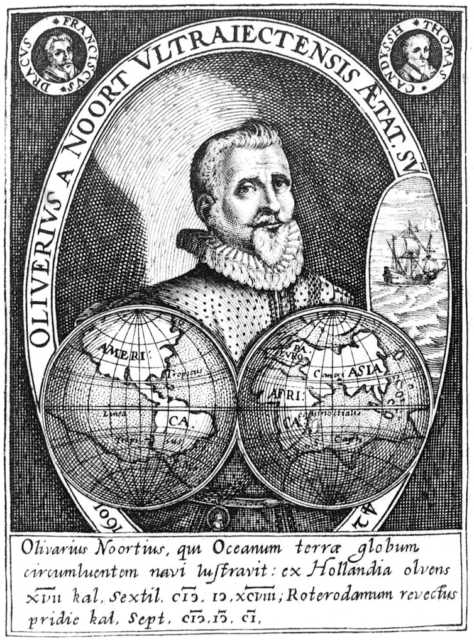

In the 1500s, three expeditions (led by Ferdinand Magellan, Francis Drake, and Thomas Cavendish) had already circumnavigated the world.

The Dutch wanted to do the same so, in 1598, they raised two fleets. One was to establish a presence in the Spice Islands (in Indonesia), and the other to open trade with China and more Southeast Asian countries.

There was, however, a problem. Spain and Portugal claimed that part of the world and they hated the Dutch.

The second expedition was lead by Olivier van Noort who commanded the Hoop, the Hendrik Frederik, the Mauritius, and the Eendracht. They left Amsterdam on September 15, 1598, and sailed to England to pick up Captain Melis – who had served as Drake’s chief pilot.

Then they went to Africa where they encountered the Portuguese who killed Melis and others. Things got worse when the Portuguese stopped them from landing in Brazil. They lost the Eendracht, renamed the Hoop as the new Eendracht, and later lost the Hendrik Frederik.

They reached the Philippines on October 16, 1600, anchoring in the Bay of Albay. Desperate for food and supplies, van Noort (who was fluent in French) pretended to be French and was allowed to land on Capul Island.

Until October 22, that is. During a skirmish off South America, they had taken captive an African slave who was loyal to Spain. The man escaped at Capul, however, so the game was up.

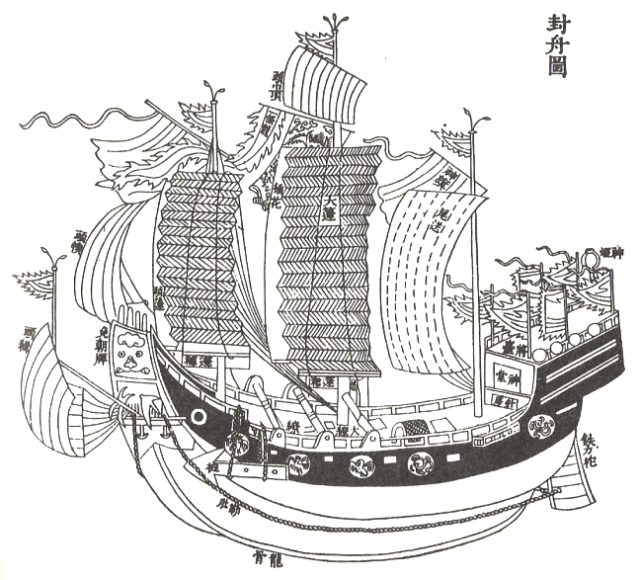

It did not matter. The Dutch fled and captured a Chinese junk loaded with provisions. Even better, its captain spoke Portuguese. He knew how to get to Manila, and how to navigate the busy Sino-Philippine-Indonesian-Malaysian-Indian route. He also knew the “open-times” (when it was not the deadly monsoon season).

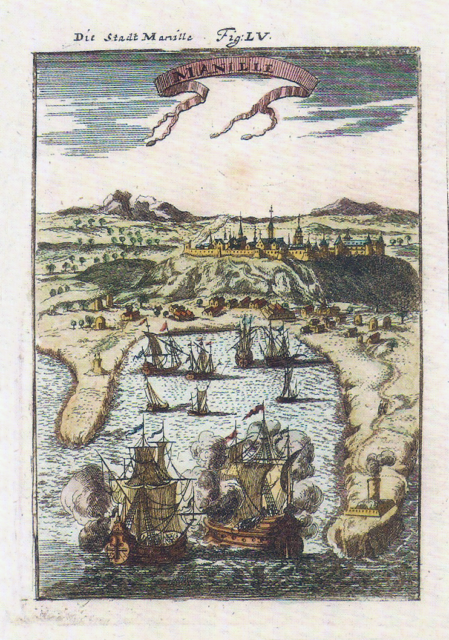

In Manila, the Audiencia (Spanish colonial government) panicked. The capital was virtually defenseless because most of its soldiers were in Mindanao. Officially Spanish, the island was Muslim territory. They were resisting Spain not with bows, arrows, and spears; but with guns and cannons.

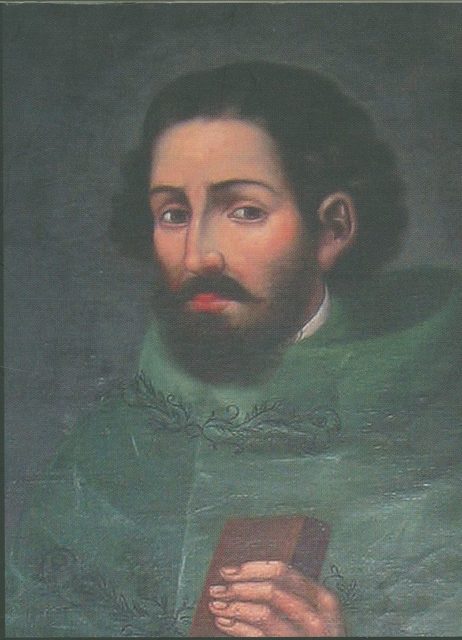

Fortunately, there was Don Antonio de Morga, Vice-Governor General of the Philippines. Taking command, he requisitioned two merchant galleons bound for Acapulco – the San Diego and the San Bartolomé. Loading 14 cannons aboard, he set sail looking for the Dutch, accompanied by a flotilla of smaller ships.

Finding them moored off Fortune Island, he refused to listen to their pleas for mercy and rammed the smaller Mauritius. After six hours of battle, however, the San Diego sank from a leak. Morga was the last to abandon ship. Regretfully, the Dutch got away.

Morga was hailed as a hero. His version was considered valid for centuries until Patrick Lize, a French maritime historian, became suspicious. Scouring through many records in different countries, Lize found that 24 people had survived the San Diego, including two Jesuit priests. Their version was nothing like Morga’s.

It seems the Spanish nobles treated the oncoming battle like a party. They boarded the San Diego and the San Bartolomé in their finest clothes and jewelry. They also brought along porcelain dining ware, beds, trunks, jars, and were attended by their servants and slaves.

Morga thought nothing of packing the San Diego with about 500 people in the mistaken belief that it would help him win a naval battle. The presence of Japanese, Arab, Indian, Spanish, Filipino, and African soldiers, mercenaries, servants, slaves, and nobles must have comforted him.

The merchant owner of the San Diego, Captain Alcega, asked for more ballast to be brought on board to balance the ship. Being in a hurry, Morga refused. He was in such a hurry, in fact, he ordered Alcega to set sail on December 12 without informing the San Bartolomé.

Alcega then asked if the nobles could at least get rid of their bedding, dinnerware, and trunks. This request was also refused. The ship began leaning to one side but, by then, they were too far out to turn back. Nobles and commoners alike were forced to sleep on deck, since Alcega refused to dump his merchandise – he had customers waiting in Acapulco.

Outnumbered and outgunned, van Noort stayed aboard the Mauritius to buy time for the Eendracht to escape. His intel had to get back to the Netherlands.

Before dawn on December 14, the Mauritius fired the first shot at the San Diego, damaging it. The Spanish did not fire back. They could not as the ship’s deck was too crowded.

Worse, it was unbalanced, so water was coming in from the gun ports. The Mauritius fired a second round, which again hit the San Diego and some of its passengers.

Desperate, Morga ordered the San Diego to ram the Mauritius. It worked. Using grappling hooks, they linked up with the Dutch ship and prepared for battle… except the Dutch had retreated below decks. Opening their gun hatches, they pleaded for mercy.

Two Spanish sailors jumped aboard and grabbed the Dutch banner, expecting others to join them. None did. They returned to the San Diego to give Morga the Dutch flag, but he could not take it.

The man was trembling on deck, wrapped in a kapok mattress. The chief gunner tried to take charge, but the nobles were having none of it. Orders had to come from an aristocrat like Morga.

Van Noort set fire to his boat, hoping to force the Spanish into uncoupling the San Diego. That finally broke Morga out of his trance, so he ordered the lines cut.

Diego de Santiago, a priest, had had enough. He ordered people to board the Mauritius – except that chaos had broken out, by then. The Dutch, tired of waiting to be boarded, returned to their deck, put out the fire and started shooting at the San Diego.

The mooring lines were severed and the San Diego began to “sink like a stone” (according to eyewitnesses). It had taken on too much water and was too heavy.

Armored men jumped overboard and sank. Unarmored nobles did the same with similar results because they refused to take off their jewelry and money pouches. Only 22 unarmored commoners survived to tell their tale.

The Mauritius joined the Eendracht, allowing the Dutch to circumnavigate the world. As Morga got to tell the Spanish king his version of events first, the other versions were suppressed.

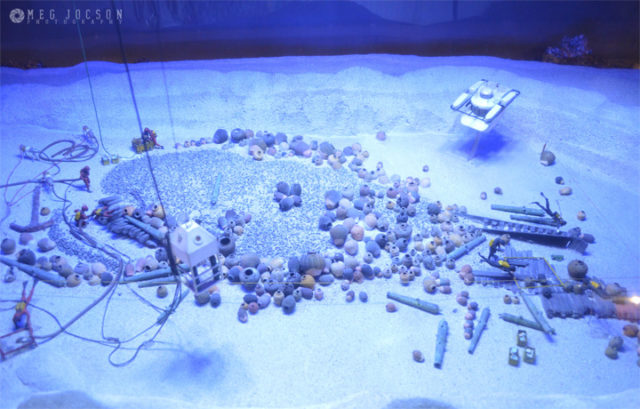

The San Diego was rediscovered by Franck Goddio (a French archeologist) in 1990. Most of its treasures are stored at the Museum of the Filipino People in Manila – an impressive display of Chinese pottery, cannons, Japanese katanas, gold and silver jewelry and coins, and so much more.