The “Croix de Guerre,” or “Cross of War,” is a French military decoration honoring people for their resistance against the Nazis in WW2. Furthermore, being appointed a “Member of the Order of the British Empire” by King George VI for services rendered in France during enemy occupation was a high British honor.

Any man who was awarded such honors must have been a remarkable one.

Only, in this case, we are dealing with a woman, and a brave and tenacious one at that.

Eileen Nearne, the woman who received these accolades, lived a perilous life in WW2. To a large extent, her exploits mirrored those of Charlotte Gray in the 2001 movie bearing the same name. The film, based on the novel by Sebastian Faulks, features the adventures of female agents in German-occupied France.

But why have most of us never heard of Eileen Nearne? Is it because her missions were so top-secret that information never leaked out? Or is it like many events during the war where some people and their heroics just pass silently into obscurity?

Fortunately, historical sources provide plenty of information about Nearne’s heritage and her daring exploits while she was stationed in Nazi-occupied France during the war.

Eileen Nearne was born in London on March 16, 1921, to an English father and a Spanish mother. Two years later, the family moved to France, where Eileen became fluent in French.

When the Germans invaded France in May 1941, Eileen and her sister, Jacqueline, escaped via Barcelona, Madrid, Lisbon, Gibraltar, and Glasgow finally reaching London. The rest of the family remained in Grenoble, France.

It is interesting to note that Jacqueline has her own remarkable secret service agent story as she would later join the “SOE” or “Special Operations Executive.”

Back in England, Nearne went to work. She wanted to serve her country. After receiving an offer from the WAAF (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force), which she turned down, she was recruited by the SOE.

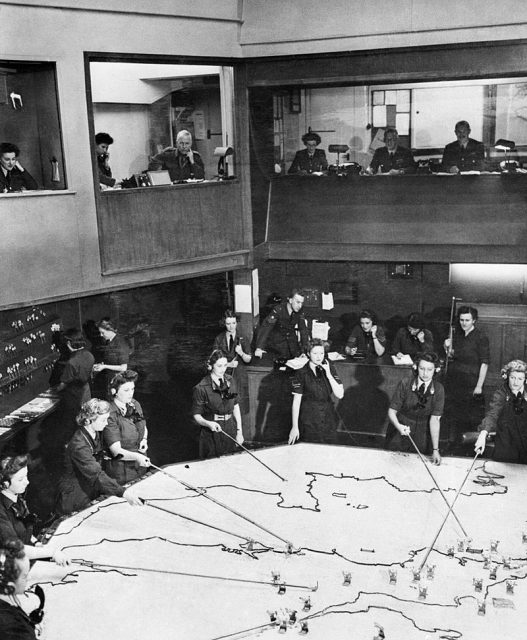

The SOE was officially brought to life on July 22, 1940. It was an amalgamation of three existing secret divisions. SOE’s primary purpose was reconnaissance, espionage, and sabotage in Nazi-occupied Europe and later occupied South-East Asia.

The agency took people from diverse backgrounds. It did not matter what class, religion, or whether the person heralded from the criminal underworld. What did matter was first-hand knowledge of the country of operation. And Eileen Nearne was perfect for occupied France. She knew the country well and spoke the language fluently.

Eileen started as a signals operator based in London dealing with secret messages from operatives in the field. During this time, her sister Jacqueline was sent to France as a courier.

Finally, on March 2, 1944, Eileen’s time came. After receiving field training, she was flown to a field close to Les Lagnys, Saint Valentin in Indre, France with a man called Jean Savy. “Operation Mitchel” had begun.

Nearne used the cover name Mademoiselle du Tort. She was also known to go under the alias Jacqueline Duterte. However, her official codename was “Rose.”

Command had given her the mission to help Savy set up a network referred to as “The Wizard” in Paris. Unlike similar operations involving sabotage and disruption, this network focussed on arranging finance for the French resistance. In over five months, Nearne transmitted 105 messages to London.

During this time, Jean Savy left Nearne on her own and returned to London to report to his superiors with valuable information about the German V1 rocket. At the time, she was unaware of the fact that the same plane transporting Savy also returned her sister to England after 15 months in France.

All alone, she continued to work diligently. At this point, she was helping the Allies with their preparations for D-Day. She also had a few close calls when the Nazis almost captured her. However, Nearne was always a step ahead of her pursuers.

On one occasion when she moved to another safe house, her role as a spy was almost uncovered.

On the train journey to her new seat of operations in the south of Paris, a German soldier kindly offered to help her with her suitcase. It contained the radio transmitter. Nearne got away by the skin of her teeth by explaining that it was a gramophone. She exited the train at the next stop and walked the rest of the way.

But the Gestapo never rested — plainclothes agents were everywhere. Caution was of the utmost importance. When she moved around the streets, Nearne resorted to looking at her reflection in shop windows to be sure she wasn’t being followed.

Even this was not enough. Eventually, her luck ran out, and she was caught.

The German secret police used the most modern frequency tracking technology. In July 1944, just after Nearne had transmitted a message to HQ in London, the dreaded Gestapo came knocking on her front door.

She barely managed to burn the messages and hide the transmitter before the Nazis barged in. Her efforts did not pay off. The Gestapo found the radio and the coding pad.

Eileen Nearne hardly ever publically spoke of what happened to her at the hands of the Gestapo at the Paris headquarters during her interrogation. All we know is that it was brutal and inhumane, like many of the things the Nazis did at the time.

However, Nearne did speak about the time after her capture during the official debriefings after the war which are documented in the British National Archives. What she describes is enough to send shivers down your spine.

Nearne was stripped naked and then repeatedly submerged into icy water, almost drowning her in the process. There were repeated blackouts due to lack of oxygen. She was beaten, insulted, and housed in the most diabolical conditions.

Yet she never divulged even a snippet of information pertaining to her fellow agents, resistance members, or her contacts and assignments from London.

Against all the odds, she managed to convince her interrogator, who repeatedly called her a liar, that she was a naïve Frenchwoman. In her story for the Nazi torturer, she was Jacqueline Duterte, a woman helping a local businessman to transmit messages she did not understand.

It was then that her experiences in a Nazi concentration camp began. Starting in Ravensbruck, she passed through a multitude of death camps. Her head was shaven, and she was immediately put to work.

At first, she refused until she understood that engaging in the menial labor was the only way to survive.

By the end of 1944, Eileen Nearne reached Markleberg Camp near Leipzig. There she worked as part of a road repair gang for periods of up to 12 hours per day. It was only when the Nazis transferred her yet again that she managed to escape with two French women.

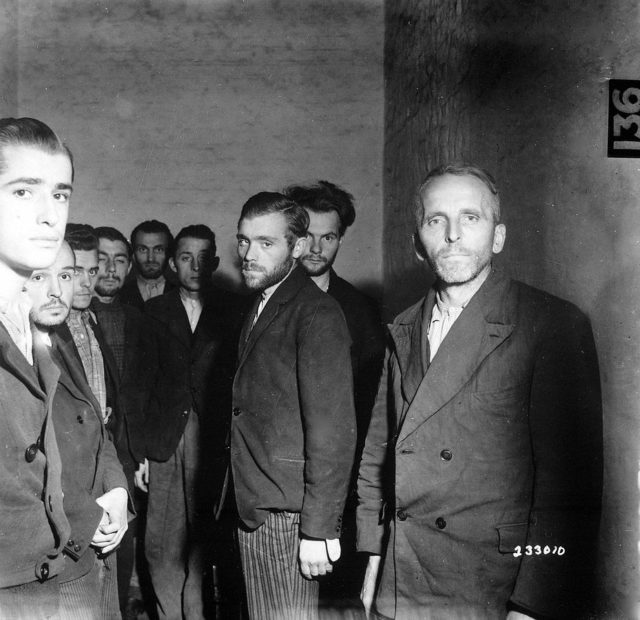

Eventually, they linked up with the liberating Americans, who thought she was a German spy. She was held along with captured SS and German spies but was released upon confirmation of her status as a spy from London.

How can anybody get through something so harrowing? We can glean some insight into Eileen Nearne’s ordeal thanks to the National Archives and the information she provided in an interview with the BBC for a documentary.

According to Nearne, when her post-war debriefers asked her how she maintained hope through such vexing times, she replied: “The will to live. Willpower. That’s the most important. You should not let yourself go. It seemed that the end would never come, but I always believed in destiny, and I had a hope.”

When the interviewer asked her what, to her mind, resulted in her eventual capture, she said “I preferred to use the old house from where I knew I could get through, but I shouldn’t have done it. That’s how I got myself arrested.”

Eileen Nearne described the Nazi officer who interrogated her with the following words: “He rushed at me and slapped me as hard as he could around the head calling me a liar, a spy, a dirty bitch. And the other one said, ‘We have ways of making people talk who don’t want to.’

“They took me into a room where there was a bath, and they held me under the water. You suffocate under the water, but you must stick to your story. I remembered what we’d been taught; never to be afraid, never let them dominate you.”

However, her ordeals during the war took their toll. Eileen Nearne never fully recovered.

When she finally came back to England, she was in a state of physical and emotional collapse. She never managed to gain employment. The war had left her badly traumatized, and she gradually disappeared into obscurity. This was so much the case that the government even cut her pension without explanation because they had forgotten who she was.

People who knew her said that she withdrew into herself and shunned any possibility to earn celebrity status and money from her wartime experiences. The only exception to this was when she traveled to Ravensbruck for a memorial.

She once told an interviewer in 1993, “It was a life in the shadows, but I was suited for it. I could be hard and secret. I could be lonely. I could be independent. But I wasn’t bored. I liked the work. After the war, I missed it.”

On September 2, 2010, the wartime heroine with the codename “Rose” died from a heart attack in her adopted hometown of Torquay in England. Because nobody knew who she was and she did not have any friends after her sister’s death, it was decided that she was to have a council funeral.

It was only when they discovered her Croix de Guerre and received information that she was, in fact, a wartime heroine that the Torbay & District Funeral Service of Torquay offered to conduct the funeral free of charge.

Once word was out as to who had died, people paid their respects to this remarkable woman who played her part in vanquishing tyranny through bravery and fortitude.

Eileen Nearne finally found peace when her ashes were scattered at sea, according to her wishes.