In April 1944, twenty-three-year-old private Walter J. Thorpe of Abilene, Kansas set out on an unlikely mission. He aspired to meet Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The private was on leave from Northern Ireland and hoped to chat with the Supreme Allied Commander, whose brother once employed Thorpe on his farm.

The enlisted man appeared at supreme headquarters and, after briefly consulting with an MP and officer, was surprisingly summoned to Eisenhower’s study. Following a ten minute wait, Ike appeared and casually asked, “So you’re from Abilene? Come on in.”

Astounded by the general’s humility, Thorpe shared the details of his improbable experience with Stars and Stripes. “We talked quite a bit about Kansas wheat, and the farm folks we knew back in Abilene. Twenty minutes later I figured I’d taken up about enough time—the general probably had a few other things to do—so I got up and got ready to leave.”

Suspecting his skeptical friends were unlikely to believe the validity of this encounter, Thorpe requested Eisenhower’s autograph for corroboration. Ike “got a piece of memorandum paper from his desk and wrote me a note. Just as I was leaving he told me: ‘I’m glad you came to see me, and if you are here again sometime drop in—you’re always welcome.’” Thorpe kindly described Ike as friendly a general as he was a farmer, neighborly and gracious.

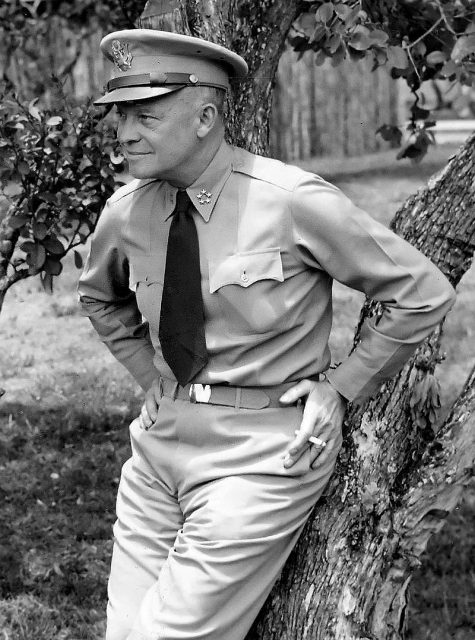

In a subsequent Stars and Stripes profile, two contrasting photos of the general characterized his persona. The captions read, “The general is tough . . . but his smile is warm.” The paper described Ike’s supreme headquarters as a place thankfully lacking “rush and helter skelter fuss.”

The office was a hub with “no noise, no excitement. The main cog of the Anglo-American military machine turns silently and surely.” Ike sat calmly in a sizable office similar to that of a business executive. The sun shone brightly through its towering windows. A name plate with four stars was perched on the ornate desk, which was tucked in a corner facing the door. “There is a large map of Europe on one wall, but it is disappointing to the visitor.”

It hung austerely without pinned flags or pencil marks. Alongside the American and British flags, the general’s red, four-star standard guarded over the gilded space. Roosevelt’s soiled letter announcing Ike as supreme commander hung from the wall as a souvenir—a token reminder of Ike’s monumental responsibilities.

Arriving at headquarters 9 a.m. daily, Eisenhower’s mornings began two or three hours earlier. A light sleeper, he often drank a full pot of hot coffee while scanning dispatches from the previous night. A chain smoker, Ike emptied four or five packs of cigarettes per day. He rarely indulged in alcoholic beverages and subscribed to the power of exercise.

Eisenhower relished a relaxing horse ride or golf match to alleviate his many strains. He hung a punch ball outside his residence, sketched the surrounding countryside, and delighted in the rhododendrons surrounding his residence. His English home was a small country cottage also occupied by friend and aide Harry Butcher.

Ike often read five or six newspapers prior to breakfast. Like his many subordinates, he thoroughly appreciated the writings of reporter Ernie Pyle. Ike’s mornings were usually consumed by appointments—especially with the likes of Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s diligent chief of staff. Ike “is a stickler for punctuality, which makes it easy for his staff to arrange his days,” Stars and Stripes observed.

“He is no hand-clapping-send-me-so-and-so commander. If he wants to see somebody he figures is pretty busy at the time, he will go himself rather than interrupt a man’s work by having him leave his desk.” The general lunched with Churchill once a week. Eisenhower always referred to the prime minister as “Sir.” Churchill always called the general “Ike.”

A dedicated team of WACs served as clerical sentinels outside Eisenhower’s study. Capt. Mattie Pinette of Fort Kent, Maine headed the loyal squad of secretaries. Pinette described Eisenhower as “an exciting kind of person.

We are not afraid of him, but we know we have got to get things right. He has a wonderful memory and is probably the most articulate of any military man. He just dictates and seldom has to change a word. Because he has such a command of language he writes his own speeches and statements himself.

There is only one trouble about him—he is a pacer. Sometimes he races off on a thought and walks ‘round and ‘round the room. We have to follow.”

Although staff freely acknowledged the general’s benevolence, behind “Eisenhower’s geniality there is a lot of toughness,” they said, “and people who think they are riding the gravy train are apt to find the brakes being applied.

And when Eisenhower gives somebody the works, they’ve had it.” Ike demanded astuteness, diligence, and a clean cut appearance. He loved nothing more than a professional infantryman—a foot soldier thoroughly aware of his responsibilities. Recognizing a proper salute as a necessary courtesy, Ike confessed at the end of one strenuous day, “Damn, my arm’s getting tired.”

Incidentally, Eisenhower was unable to return a “by the book” salute since he once broke the fingers of his right hand playing baseball. His fingers “never properly straightened out.”

While Eisenhower enjoyed life’s occasional comforts, Stars and Stripes concluded, “there is not much spare time in the life of the Supreme Commander these days. There is a day coming up sometime soon when he will send his troops across the water against the Germans. He has a bitter hatred for the enemy.”

After witnessing Germans bomb a hospital, Ike subscribed to “the only good German is a dead German mentality. He is satisfied that once he gives the signal he will have the men and material to perform the task he has been given—the liberation of Europe.”

Visiting those who would bear the brunt of the invasion was not beneath Eisenhower’s stature. On March 30, Ike spryly inspected fighter groups of P-38s and P-47s. Giddily climbing into a Lightning, the general squeezed off some 200 rounds from the parked aircraft. He thereafter learned that pilot J. M. Morris had already destroyed seven enemy planes.

Shaking the officer’s hand, the general declared, “I want to congratulate you, Capt. Morris. Why didn’t you tell me you had shot down seven planes? I hope you make it 70.” Courtesy calls were not a waste of the commander’s time and never were they mere public relations stunts.

The general was deliberate in his inspections of British troops as well. James Long of the AP wrote on May 26, “General Eisenhower, whose word will hurl the full might of an allied assault upon the Nazi-bound continent, returned to supreme headquarters today after a swift inspection tour of British land forces under his overall command, well pleased with the thorough training of this army Britain has assembled to wring vengeance for the Dunkerque of four years ago.”

Ike pronounced the men “fit and ready for their part in the job to come.” He conveyed that same message to King George VI, with whom he deliberated that afternoon.

Only days earlier, Ike offered a captivating presentation of invasion plans to the King and high command at London’s St. Paul’s School. In less than ten minutes, Eisenhower imparted the daunting complexities of Operation Overlord to perhaps the greatest war council ever assembled.

One American admiral reflected that the operation’s success would require “nothing less than divine guidance.” Ike’s confident charm at the briefing did not hurt either. “It has been said that his smile is worth twenty divisions,” the admiral confessed. “That day it was worth more.”

Young correspondent Andy Rooney was pleasantly caught off guard by the general’s demeanor. Ike “was somehow lovable, being, at the same time, competent and bumbling,” recalled Rooney.

Even more revealing were Eisenhower’s pronouncements of the importance of a free press in wartime. “I believe that the old saying—public opinion wins wars—is true,” he admitted to journalists. “Our countries fight best when our people are best informed. You will be allowed to report everything possible, consistent, of course, with military security.

I will never tell you anything false.” On a personal note he added, “I should feel disturbed if I thought that I or my public relations staff were held as anything but friends of the press.” Wherever possible, Dwight Eisenhower sought to prevent truth from becoming a casualty of war.

Another Article From Us: Eisenhower Came Out of Retirement to Denounce the Movie “Battle of the Bulge”

Learn more at www.jaredfrederick.com Jared Frederick is an Instructor of History at Penn State Altoona and the author of Dispatches of D-Day: A People’s History of the Normandy Invasion.