War is full of brief encounters. A sudden glimpse of the face of an enemy; the brief sighting of an enemy submarine; or seeing a wounded man in agony carried by on a stretcher. When men are taken captive, these meetings become all the more poignant. Prisoner and guard trapped in close quarters, usually under stressful conditions.

One such encounter, between a US Coast Guard Cutter’s captain, and the captain of a German submarine captured this tension.

On May 19, 1945, the German Submarine U-234 sat moored next to the US Coast Guard Cutter Argo in New Hampshire, USA. Her 47 enlisted crew were brought out on deck, and formed a huddle on Argo’s fantail, waiting to disembark from the cutter.

The submarine’s Captain, Kapitan Leutnant, Johann-Heidrich Fehler, stepped up to the gangway and faced his Coast Guard counterpart, Lieutenant Elliot Winslow. These two men could not have been more different, but the war brought them into contact, if only for a brief moment.

Fehler, a proud German sailor, was born in 1910, just west of Berlin. On graduating from high school, he signed on a German sailing vessel. Two years later, he joined a German freighter. He attended the German Merchant Marine Academy graduating as a Mate and then joined the German merchant fleet.

In 1933 he became a member of the National Socialist Democratic Workers Party (NSDAP or Nazi Party) and became devoted to the ideals of Adolf Hitler and his followers. In 1936, as Germany began rearming its military, he joined the German Kriegsmarine as an Officer Cadet in the Reserves.

When WWII began in 1939, he was called into active service onboard the Auxiliary Cruiser Schiff-16 Atlantis. It was a converted merchant vessel, with hidden guns, designed to blend in, and then raid Allied merchant convoys.

Fehler discovered he had a knack for explosives and was the ship’s demolitions expert. He earned the nickname “Dynamite” by the crew as he used any excuse to carry out explosions.

When a British warship discovered what the Atlantis was up to the entire crew transferred to the Python, another German auxiliary cruiser. However, it too was uncovered. After scuttling Python, Fehler, and his crew were adrift in lifeboats, but were rescued by a group of German U-Boats.

-

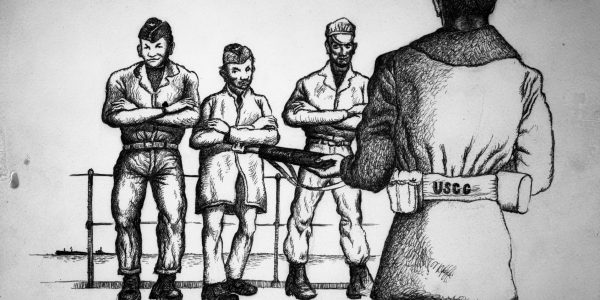

A drawing of the German prisoners illustrated by one of Argo’s crew

It was Fehler’s first experience on submarines. He had supplied them but rarely had he been able to spend any time on board. He made up his mind, if they returned to Germany, he would join the U-Boat Corps.

He did, and by 1944 this ambitious young naval officer was in command of his own submarine, a type XB, U-234. They were designed for minelaying and resupplying the attack subs deep in the Atlantic. Disappointed by his lack of offensive opportunity, Fehler reluctantly took the post.

-

Surrendered German Submarines at Portsmouth Navy Yard, 1945

However, his final mission was to prove a much more important task. The U-boat was ordered to transport 300 tons of equipment, personnel, and blueprints to Japan, in a last ditch effort to keep Japan in the war. They set out on April 16, 1945, steaming west.

At that same time, Elliot Winslow was in command of the US Coast Guard Cutter Argo, on convoy patrol in the Atlantic. Winslow was almost the exact opposite to Fehler. He was originally a paint salesman, and joined the US Navy in 1940, at the age of 31.

-

USCGC Argo underway

Unlike Fehler, who joined for patriotic fervor, Winslow joined to avoid having to make good on his marriage proposal. In 1941 he was called to active service as a Seaman Second Class. Shortly after the Pearl Harbor attacks on December 7, 1941, he applied for a commission in the United States Coast Guard Reserve, which needed skilled seamen and leaders to bolster their rapidly expanding fleet.

By 1942 he was an Executive Officer on the Coast Guard Cutter Menemsha. After attending the Navy’s Anti-Submarine Warfare school, he was assigned to the Argo. By mid-1943 he was her Executive Officer, and two months later, her Captain.

Now a full Lieutenant Winslow had his own ship and a skilled crew. He put this combination to good use, in numerous patrols, and engaging in hair-raising rescues. Most notably, the St. Augustine, a 300-foot steaming yacht converted into a gunboat.

By May 5, 1945, both men were in the Atlantic. Karl Doenitz, the new German Chancellor, issued an order for all U-boats to surrender to the nearest Allied ship.

Fehler wanted to surrender to the Americans believing he and his men would receive better treatment. He found USS Sutton and the crew gave themselves up.

Meanwhile, USCGC Argo and Lieutenant Winslow were busy ferrying submarines to US Navy bases. The Germans were surrendering to any warship carrying an American flag, and it became Argo’s task to ensure they made it to an American port.

Argo took over command of U-234 on May 19, 1945. Fehler went on board Argo and offered a handshake to Commander Moffat, a US Navy representative. Denied this, Fehler made a remark about how soon Germany would rise again, and perhaps then the Americans would surrender to him. This began an intense dislike between Fehler and his American captors.

Fehler complained his men were being treated unfairly by the Americans. His crew was forced to sit on the deck, with their arms squarely across their chests, and armed Coast Guardsmen were standing over them. Fehler objected loudly and angrily.

-

U-234 surrenders to USS Sutton, in 1945

Winslow was furious. He proclaimed any prisoner who moved, even to scratch his face, would be shot. He knew he could not give them any leeway and wanted to put an end to the protests immediately.

The final meeting between these two captains came later that day. Winslow was watching at the gangway, while the senior prisoners from U-234 disembarked. Luftwaffe General Kessler was the first to depart. He politely asked permission and Winslow silently pointed to the shore.

Fehler then approached, still angry. He again protested his men had been mistreated saying Winslow and his crew had treated his men like gangsters. Finally, Winslow’s anger got the better of him. He yelled “That’s what you are. Get the hell off my ship!” as he pointed to the gangway.

Knowing he was defeated, but pleased he had angered his opponent, Fehler disembarked with a slight smirk on his face.

These two men, on opposing sides of the war, and from very different backgrounds, met for only a brief moment during the peace, and almost immediately were at odds with one another.

Their story, however, gives a glimpse of life in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. For four years, these enemies had fought tooth and nail to destroy one another. Once the war was over it was not so easy to forgive and forget.