The English eventually forced their way across the bridge but were met and outflanked by the larger force. The Duke of Clarence was killed, and the English force was routed.

“The enemy of my enemy is my friend.” This ancient saying has been invoked many times throughout history, but one of the most successful examples of this logic was the Auld Alliance between France and Scotland.

Although the Auld Alliance was founded out of a mutual hatred of England in 1295, the French and the Scotts grew closer over time.

France sent significant aid to Scotland, particularly during their Second War of Independence against England. In return, Scotland reinforced the French army during the Hundred Years’ War.

It was during the latter days of the Hundred Years’ War that the French King created an elite personal bodyguard comprised of Scottish warriors called the Garde Écossaise (Scottish Guard).

Foundation and Honors

Scottish forces served in the French military throughout most of the Hundred Years’ War, earning a reputation as capable fighters in the process.

A Scottish force under John Stewart, Earl of Buchan, and Sir John Stewart of Darnley arrived in France in 1419 to great fanfare. The Dauphin (heir apparent to the French throne) was in desperate need of help as his father, King Charles VI, suffered from a form of insanity and had few allies.

For his own safety, the Dauphin picked out around 100 of the finest Scottish warriors to be his personal bodyguard, thus creating what would come to be known as the Garde Écossaise. In its early days, the Garde was primarily composed of archers, with some men-at-arms.

The Dauphin took further actions to secure Scottish loyalty. The Earl of Buchan was given land at Châtillon-sur-Indre, Stewart of Darnley was provided with land at Concressault and Aubigny, and several other Scottish leaders received land and castles before they even fought a battle on French soil.

The Scottish Army in France

However, that soon changed at the Battle of Baugé, as the French were still reeling from the Battle of Agincourt. The Scots’ performance at Baugé ended up leading to one of their most heroic victories.

Accounts of the battle vary by source, but it is clear that the English, under the Duke of Clarence, attempted to catch the Franco-Scottish force off guard. However, the Scots turned the tide of the battle by holding their ground at a bridge as the English tried to cross.

French forces soon reinforced them, leaving the English badly outnumbered as they had only brought part of their force for this assault. The English eventually forced their way across the bridge but were met and outflanked by the larger force. The Duke of Clarence was killed in the melee, and the English force was routed.

Legend has it that Pope Martin V, upon hearing of the battle, said: “The Scots are well-known as an antidote to the English.”

In return for their service, Scottish leaders were granted more lands. The Earl of Buchan was given the title Constable of France, essentially making him commander of the French armies. Unfortunately for the Scots, this success did not last.

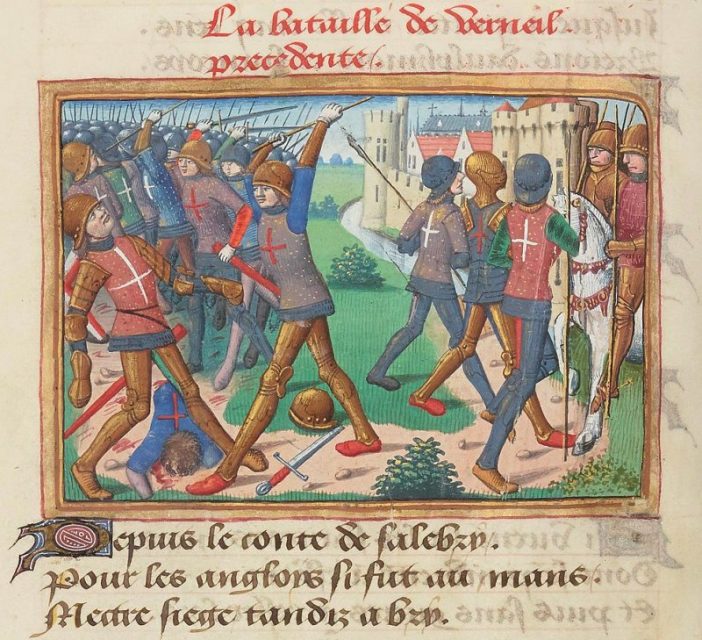

The French-Scottish force suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Cravant during which Buchan was captured. The French forces fell back during an attempted river crossing, and the Scots were cut down as they stood alone against the English.

Buchan was exchanged but then killed during another disastrous defeat at the Battle of Verneuil after French troops once again retreated early in the battle and left the Scots to face the English alone.

However, the Garde Écossaise remained and continued to prove themselves throughout the Hundred Years’ War and beyond.

Finest Moments

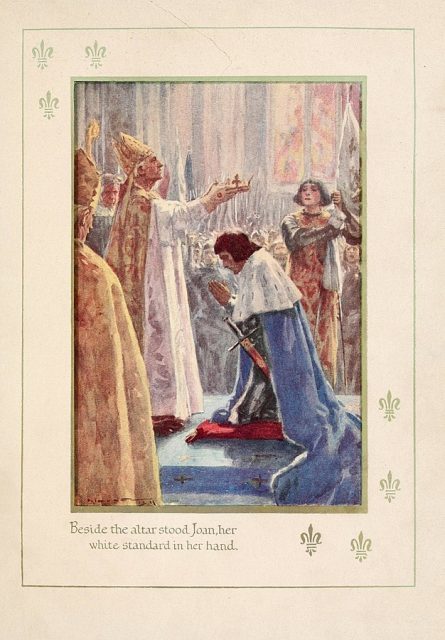

In 1429, a mere five years after the French-Scottish defeat at Cravant, Joan of Arc marched into Orléans to the sound of bagpipes. She entered the city accompanied by a guard of around 60 Scottish men-at-arms and 70 archers. The pipers played Hey Tuttie Tatie – the song that, legend has it, was played for Robert the Bruce as he marched into battle at Bannockburn.

In fact, Scottish soldiers made up a significant portion of the relief army as a whole in addition to Joan’s guard.

The Scottish Guard stood by Dauphin Charles VII on several occasions, ensuring their continued role as his protectors. They were likely present to protect the Dauphin during the assassination of John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy.

The Garde Écossaise saved Charles VII’s life in 1442 when his lodgings near Gascony were set on fire. Historian M.G.A. Vale writes that King Charles “escaped death, but only through the prompt action of his Scots archers, who made a breach in a wall by which he escaped.”

The king continued his campaign, taking control of Gascony and eventually securing the French victory in the Hundred Years’ War.

However, Charles VII was not the only French king saved by the Scots. In 1465, King Louis XI found himself at war with the League of the Public Weal – a group of French nobles who resented Louis’s attempts to centralize power.

During the particularly pitched Battle of Montlhéry, the King and the Garde Écossaise found themselves in the middle of a melee. At one point, Louis’s horse was killed under him, and he fell to the ground. The League’s forces began to celebrate and proclaim that the king had been killed.

However, reports of his death were premature. The Scots Guard moved in to secure the king, lifted him to his feet, and got him a new horse. Undeterred, the king and his Scots plunged back into the heart of the battle. Although the results of the battle were mixed and some of the Scots Guard were killed, Louis went on to win the war.

Later Years and Dissolution

The Garde Écossaise continued to guard the French Monarchy until the French Revolution disbanded it. Even then, the Garde was reformed along with the monarchy during the Bourbon Restoration.

Their duties included guarding the French king at all times and even escorting his food from the kitchen to his table. A group of 24 specially selected members served as Gardes de la Manche (Guards of the Sleeve), so named because they were in such close proximity to the king during ceremonies that he could brush them with his sleeve.

Throughout the centuries, several notable Scottish Guard commanders married French nobles, bringing the nations closer together.

One of the most significant examples is Robert de Coningham, a Captain of the Garde who married a noblewoman named Louise Chenin. Together they built Cherveux Castle, which featured carvings of two musicians, one playing the bagpipes and the other playing the rebec. Some of the soldiers permanently settled in France as well, forming a “Lost Clan.”

By the reign of Louis XV (1715-1774), the Scottish Guard was comprised of 330 men with 21 officers and had transitioned to being a mounted unit. Despite this change, the Scots still fought with the traditional claymores, distinguishing them from all other heavy cavalry of the era.

Read another story from us: The First Gunslinger: The Lone Gunman at Orleans

The Garde Écossaise was disbanded permanently in 1830 with the fall of the French Monarchy, over 400 years after they were founded. But they were still honored with the title “Les Fiers Ecossais” (The Proud Scots).

Throughout their 400 years of service, the Scots Guard repeatedly proved themselves as elite soldiers in battle, saved the king multiple times, and created a legend that should be remembered to this day.