Almost every country in the world has had its own fair share of internal crises, disputes, and wars – some more than most. South Africa, a nation with an agenda that is “inspiring new ways,” witnessed a period of widespread killing and riots in its very own Kwazulu-Natal province during the 1980s.

The civil war, which lasted for over 10 gruesome years, was a political struggle between the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) and the African National Congress (ANC) which, despite being under political ban at the time, still had a paramilitary wing in the MK (Spear of the nation).

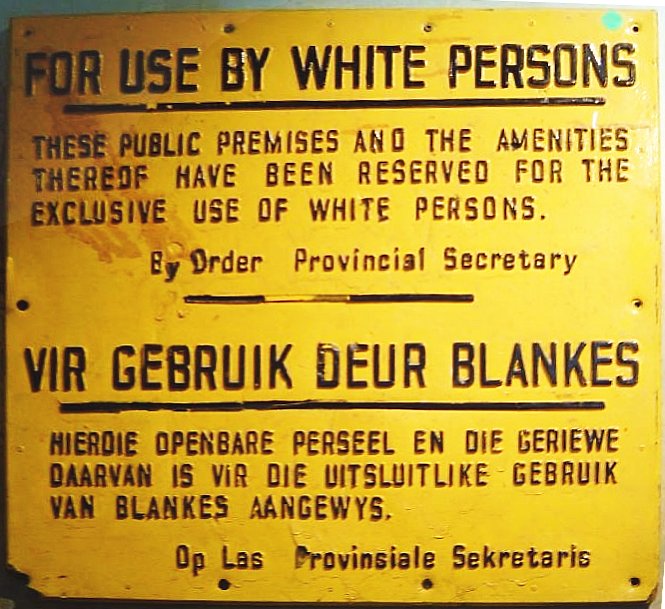

One party’s concerns for ethnic and tribalistic progress opposed another’s quest for national unity and this lead to the dissolution of what used to be common ground between anti-apartheid activists. Also, the United Democratic Front (UDF), a large anti-apartheid political organization aligned with the ANC, and this caused problems with the IFP.

A social crisis spread across the nation; the detention of youths at the Lay Ecumenical Centre in Edendale for ANC activity, and the establishment of vigilantes (the Oqondo) by Rev. M. Majola to counter the increase in numbers of youth activists, had created an environment of constant tension, which regularly spilled over into fighting.

UDF supporters, with their familiar chant of “UDF unites, Apartheid divides,” could be heard on the dark streets of Sobuntu. They fought for racial equality. Many of the nation’s indigenous blacks had lost their jobs as a result of an economic crisis in the price of Gold, one of the country’s major sources of revenue.

The death of Graham Radebe, only 17, at the hands of a police officer sent further waves of unrest through the young black activists, and what started out as non-violent protests soon turned into expressions of utter rage and sheer madness.

The IDF was known for their disdain of governmental sanctions and stood in opposition to them. They were the political power in the Zulu homeland of KwaZulu Bantustan.

Then, protests against the harsh sentencing of their leader, Ben Dikobe Martins, fell on deaf ears and resulted in the deaths of several people. The wave of violence rolled across the state, eventually leading to the declaration of a partial State of Emergency (SoE) in 1985 and a full nationwide SoE in June 1986.

Some members of the IFP then organized the kidnapping and murder of three residents from the town of Mpophomeni, two of which had been involved in the controversial BTR Sarmcol strike. This set of a chain of massive killings with the death toll averaging 14 every month for a seven-month period.

The South African Police (SAP) practically turned a blind eye to these events and in some cases even supported vigilante acts perpetrated by Inkatha members who had gone on a killing spree against their perceived opponents, namely the self defence units that had been set up by UDF youth loyalists who felt the need to take up arms in order to protect themselves and fellow UDF members.

Wives lost their husbands and children, their brothers and fathers in what seemed to be an endless political war. In a bid to fight apartheid in South Africa, both parties had lost their way and were now killing each other. However, the Inkatha Freedom Party claimed that all the allegations against them were false.

David Ntombela, the KwaMncane induna and an active supporter of the IFP, had threatened action in response to the banning of IFP-driven buses through the valley and lived up to his threats when they apparently fell on deaf ears.

In what was to be known as Operation Cleanup, in January 1988, Inkatha members armed with heavy duty weaponry raided the area, leaving 200 dead in their wake. Once again, they had received the support of the SAP, who neglected their duty to protect and serve by arming the Inkatha vigilantes as well as firing upon the valley residents. Ntombela’s message was simple and clear: “Support the IFP or die.”

The death of members of the Sithole household, who were active Inkatha members, brought about speculation that the Ntombela goons, in conjunction with the SAP, had targeted the wrong house in a bid to eliminate UDF supporters.

In another version, the idea was to use the death of the family to incite further hatred in the hearts of Inkatha members against the UDF. UDF supporters were now being hunted like animals by the SAP and Inkatha members across the province.

The ANC at the time was banned from any form of political activity in the nation, and when the Inkatha began to suspect the involvement of the ANC in a church-led peace initiative backed by COSATU, a non-ethnic worker-oriented trade union organization, and the UDF, it was rejected by the IFP. The church, noting that the former ANC member and Inkatha party leader, Mangosuthu Buthelezi was an Anglican tried to settle the dispute, all to no avail.

The dispute reached its climax in what turned out to be a seven-day war in the region which began on the 25th of March, 1990. UDF supporters ambushed buses returning from an Inkatha organized rally; they threw stones at the buses, with the act resulting in the death of several Inkatha members.

In a counter attack, the Inkatha supporters put together a well-armed 3000-man mob and mounted an attack on the valley. Houses were burnt to the ground and homes were destroyed. Ntomebela was described as being very active in the mobilization of the Inkatha-led riot. It also received the aid of the SAP and kitskonstabels. The week-long attack was termed a success, much to the anger and distress of the common man.

In the aftermath of the riot, the bodies of two women were displayed carelessly on the streets of Songozima; it was indeed a time of fear, hate, and bloodshed. Subsequently, a group of women organized a march in peaceful protest to the killings but they were met with clouds of tear gas actively rained upon them by the police. The violence, however, died down over the weekend.

In 1993, a truck carrying school children was ambushed by a gang of six gunmen. The attack resulted in the death of three children and three adults. The father of the murdered children was an active Inkatha member and the Inkatha supporters blamed the act on the ANC, who by now had had the ban on political activity lifted and were once again involved in the nation’s politics.

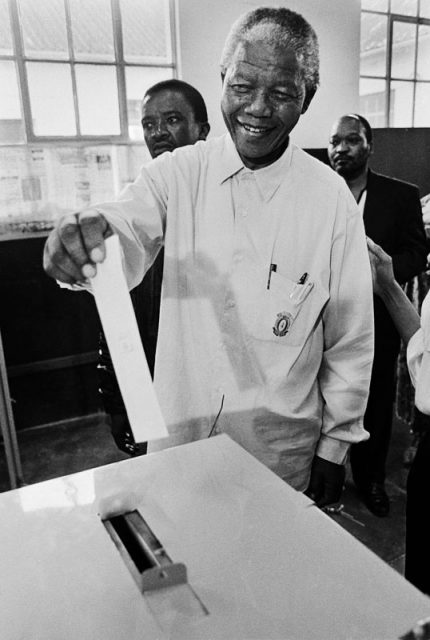

The election of Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela as president of South Africa in 1994 clearly favored the ANC, However, the reality of having a black president brought relative peace to the region. Also, the actions of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission set the nation on a course of attaining a free democracy.

The explanation given for this campaign of violence is one where political extremists who took advantage of the gradually declining state of the nation’s economy and standard of living experienced by the black populace. An increase in taxes, fares, rent, and the unemployment rate all brought about the build-up of factions seeking to bring about a change in the government by any means necessary.

With the inception of multiracial democracy in 1994, South Africa’s military arm, the SADF, was merged with the ANC’s Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the self-defense units of the IFP, and the Azanian People’s Liberation Army of the PAC to form the South African National Defence Force (SANDF).

The war, although still ongoing, has now, thankfully, been reduced to sporadic events around the country.